John August Swanson at work in his studio in spring 2021 (Cecilia González-Andrieu)

One afternoon last spring, as John August Swanson and I sat in his tiny kitchen, he stopped speaking and listened intently. "That's a new song," he told me with his characteristic gentleness. I peered out the window, straining to hear what he heard. "I've never heard that bird before," he added with the assurance of someone who speaks the language of birds.

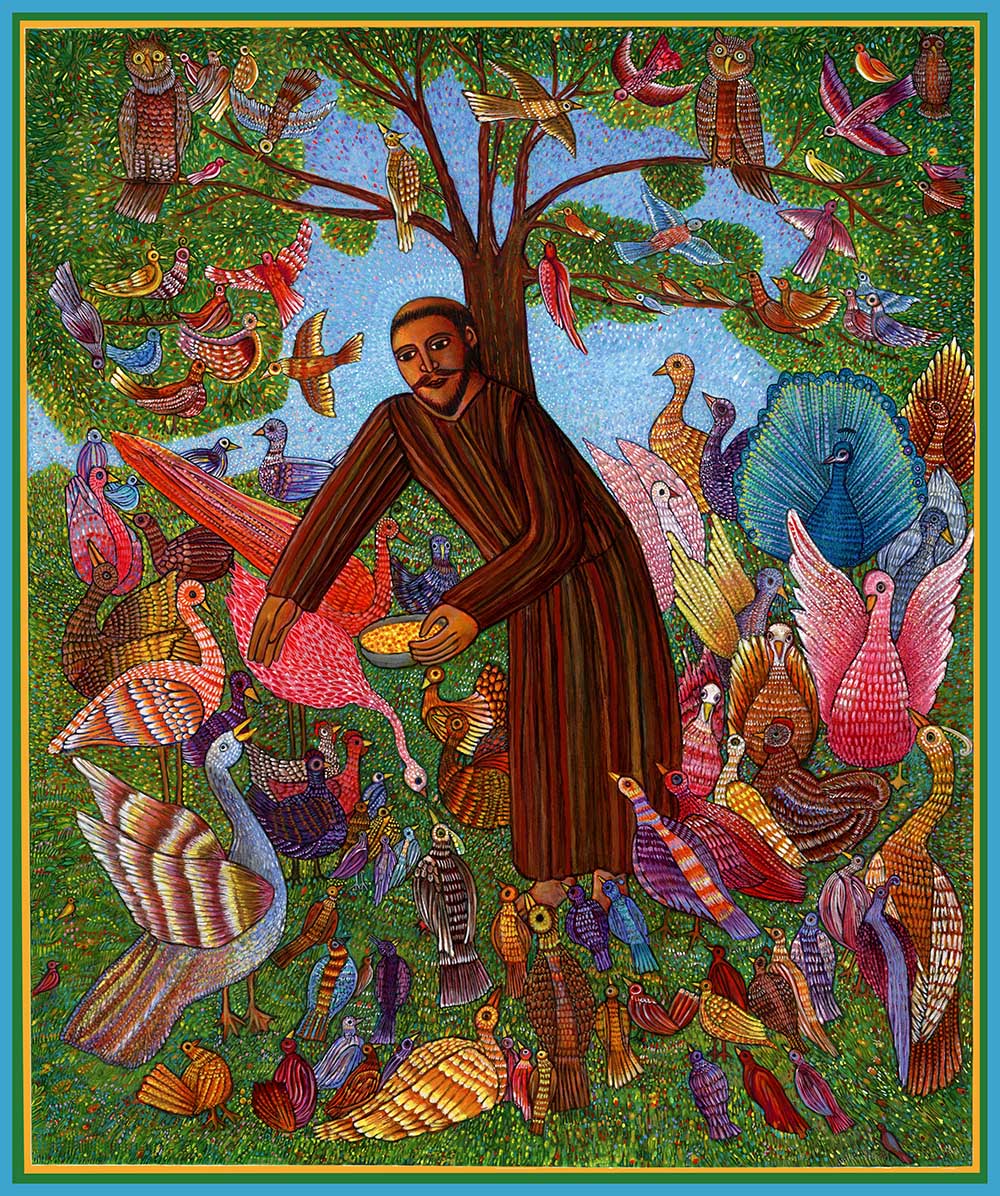

The moment brought to mind two of Swanson's loves and two stories that have much to do with him — Juan Diego and St. Francis. If he had not paid attention to the birdsong, Juan Diego would have never come upon the hill where la Virgen de Guadalupe waited for him. St. Francis was a favorite subject in Swanson's art, precisely because he expressed a kinship with the world that reverenced and defended the dignity of everything.

Attentiveness and surprised wonder at everything and everyone he encountered were what fed Swanson's extraordinary art and his faith; the canvasses communicated the way he lived and saw the world.

Swanson died of congestive heart failure on Sept. 23 at the St. John of God Care and Retirement Center in Los Angeles, after being admitted there for hospice care in August.

When his health issues were announced, hundreds of people communicated their prayers and shared their memories online. I was struck by the diversity of those who loved him and were now praying together — other artists, entire religious congregations, parish communities, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Methodists, Jews, Muslims.

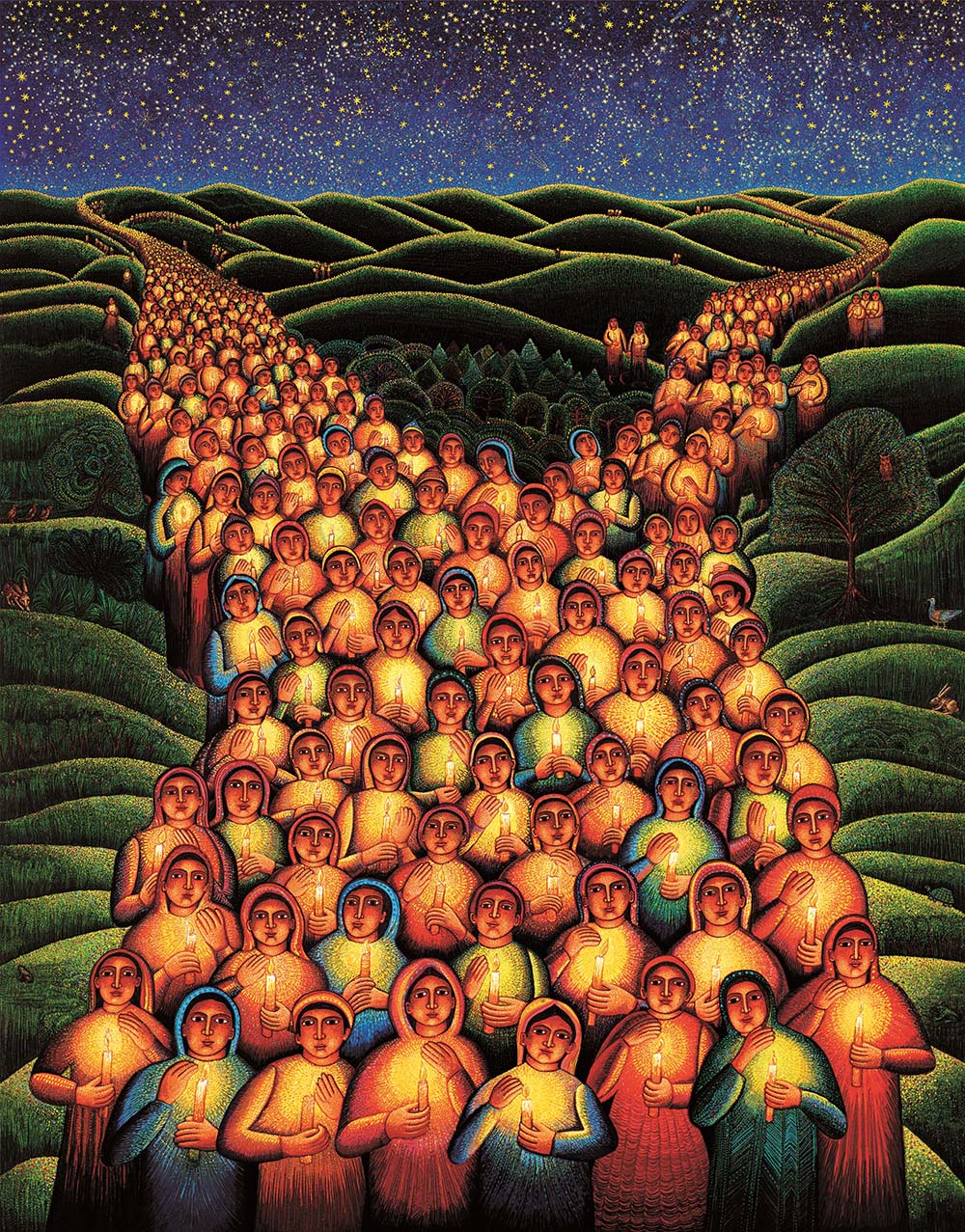

The messages poured in much as he had dreamed in his "Festival of Lights" (2000). The entire world was coming together in a global vigil for the great artist. It was truly about the glory of God's beautiful world.

"Festival of Lights," ©2000, by John August Swanson (Courtesy of the Studio of John August Swanson, www.JohnAugustSwanson.com)

Swanson and I had been collaborators and friends for years: the artist and the theologian who writes about art. He sometimes looked at me after I commented on a particularly powerful theological insight in his work and said humbly, "But it was just spontaneous, I didn't really think about all that as I worked."

I reassured him; the depth of theology was all there because he had been so open to the workings of the Holy Spirit. He smiled, knowing that was how he lived.

Yet somehow this was also the reason that his works are part of the collections of the Vatican Museum, three of the Smithsonian's galleries, the Art Institute of Chicago, The Tate in London and the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. This summer, I began work on a book on his life and art, but our time was unexpectedly cut short.

John August Swanson was born in Los Angeles on Jan. 11, 1938, his mother a Mexican seamstress and his father a Swedish vegetable seller. Both of his parents were immigrants, an unlikely pair escaping violence and poverty in their native countries and trying to survive through the Great Depression and its aftermath.

These conditions of hardship resulted in his father's cyclical absences and early death. Swanson was raised in a multigenerational Mexican home, learning to link faith and social justice activism from his mother, Magdalena. A sensitive musician (he played the violin since childhood), Swanson longed to help the world, while he struggled with debilitating shyness and undiagnosed dyslexia.

It was as he studied with Corita Kent, at the time a nun and member of the Immaculate Heart Community, that he discerned the power of the visual arts to invite communities to build a better world. From his time with Corita, he developed a close link to the two things that most mattered to him, social justice and the power of art. He would now communicate these through the vibrant prism of his faith.

In Swanson's art we see a prophetic vision of a world in which love abounds, resistance to evil is intentional, and a transformed world is possible.

"Francis and the Birds," ©2015, by John August Swanson (Courtesy of the Studio of John August Swanson, www.JohnAugustSwanson.com)

As we worked together this past summer and his health deteriorated, we started to speak about the gifts he has given the world and the inspiration he has been to young people.

One of them, my former graduate assistant Emilie Grosvenor, now completing a doctorate, was in touch with me often asking about "Mr. Swanson." Emilie was born in the same city as John half a century later and yet to watch them together was to learn about the timelessness of the power of beauty. I asked Emilie to tell me about her experience of him, and from Scotland she wrote:

To look at Swanson's serigraphs is to be reminded that Godself is always being revealed at the peripheries, in the most unlikely of places, and in the most unlikely of people: in the affection and devotion of Ruth to Naomi, in the Fool who is awake to God's creation as the others sleep, in gathering communities, in quiet works of mercy, and in an immigrant family answering the call of God by flying to safety.

Everything is more than it seems. Every detail of his work reveals the inbreaking of the beauty and justice of God's kingdom. A tree, the sun, a ladder; these are not mere objects. They are imbued with life through layers upon layers of color and meticulous detail whose playful light is cast and reflected upon every other subject of the serigraph, no matter how inconsequential one may wish to deem the detail. Therefore no subject of Swanson's work is alone in his pieces. Even in works like Jester (2001) where, apart from the Jester himself, the others remain asleep, the stars he reaches for are filled with such dazzling layers of color and light that it is impossible to see them as anything other than alive themselves. They accompany the Fool. They watch over him. They reflect the community of God's Reign back to him, and he reaches for it.

John August Swanson didn't just exhibit this call to community amongst God's creatures in his artwork. He lived it privately and politically. He had a quiet way of speaking, and a deep interest in the well-being of whomever he was speaking with. He was generous in his listening, exhibiting an all too rare genuine curiosity at the details of a person's joys and struggles.

In a world where so many of us live in isolated bubbles, Swanson was the opposite. Even while in the hospital, he tried to remember the name of every nurse, doctor, assistant and custodian. He wanted to know their stories, and you had a feeling that at any moment a new artwork would spring from his imagination and this person's precious life would be preserved on one of his canvasses.

Liturgical musician and theologian Tony Alonso, whose gleaming grand piano sits under the gaze of the community in Swanson's masterpiece "The Procession" (2007), told me recently of their first encounter.

"I met him in my first Religious Education Congress in 2003. I was 23. I walked by his booth. It was the first time I had seen his art (or anything like it). I spent every penny they were paying me to be there (and a little more) to purchase 'The Washing of the Feet' (2000)."

The young musician was then surprised to find that the artist of such a wondrous work was actually there, they started up a conversation and a friendship that endured until the end.

Swanson was very much like his art, childlike at first and then suddenly pulling you into the depths. In recent years, he had returned to his early practice of making posters, now merging years of luminous artwork with the social concerns that were breaking his heart.

He made posters against the death penalty, for immigrant's rights, for just wages, and for one of his greatest concerns, peace, and against nuclear weapons. Since Pope Francis' election, he found another Francis who shared his loves. He also made posters to promote Francis' encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" and environmental justice.

His very last painting is "The Storm," which he created inspired by Francis' urbi et orbi message on March 27, 2020, and the unforgettable images of the Holy Father alone in the rain as the world reeled from the pandemic. He showed it to me periodically as it developed. The storm clouds grew and burst with jewel colors; the oars plunged into the stormy sea. It is an image of a community rowing together into the deep, the stronger ones rowing for the little ones, Mary and her infant Son in the boat with us, sharing the journey, none of us alone.

Among the many honors and awards Swanson received, the very last one, the President's Award granted by Loyola Marymount University while he was in hospice care, celebrates an entire life dedicated to bringing people together as advocates for peace, social justice and the environment.

Advertisement

On receiving it, he said, "There's so many different groups in Los Angeles working on social justice, it takes all of us." His last wish was always his first wish, that we all work together to "bring more beauty into the world."

As Swanson said goodbye to all of us, for this next part of his journey, I like to think of the view he has of us now. I think Jesuit Fr. Randy Roche, the director of Loyola Marymount University's Center for Ignatian Spirituality and our mutual friend, wrote to me, "There was a recent posting from God's Administrative Assistant: they need an artist who knows how to illustrate faith and love in brilliant heavenly colors."

I'll be looking up at the sky to see what new colors John adds to the communion of saints. He is surely there.

Funeral arrangements are pending the completion of the renovated Chapel at the St. Camillus Center for Spiritual Care, which will feature a large collection of his works. As was John's wish, memorial gifts may be made to St. Camillus Center for Spiritual Care or to a Catholic Worker house near you to continue their work.