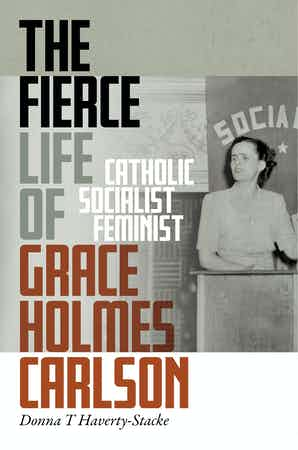

Grace Holmes Carlson (front row, far right) poses with 14 of the 18 activists convicted of trying to overthrow the government under the 1940 Smith Act. Carlson went to prison in 1943. While there, she supported young women jailed because they had taken up prostitution to help their families survive. (Minnesota Historical Society, CC BY-SA 3.0)

At a time when people thought a woman’s place was in the home, Grace Holmes Carlson (1906-1992) thought her place was on a picket line protesting for the rights of workers.

Relatively unknown today, she made headlines in the 1930s, '40s and early '50s for her social activism, as well as her pro-union, anti-capitalist and anarchist views.

Donna T. Haverty-Stack’s book, The Fierce Life of Grace Holmes Carlson, Catholic, Socialist, and Feminist, summarizes Carlson's life, explaining who she was and what she did. As Haverty-Stacke puts it, Carlson's "life certainly has much to teach" readers about standing up for one's principles.

She had been a devout Roman Catholic until she became a Marxist, a Trotskyist and a founding member of the Socialist Workers Party and an atheist.

During her Marxist years — late 1930s to 1952 — she wrote numerous articles promoting justice for workers. Her speeches railed against capitalism and for civil liberties. She became a Socialist party leader and lectured to groups throughout the United States.

She was the only woman among the 18 activists convicted of trying to overthrow the government under the 1940 Smith Act, which was later declared unconstitutional. She was sent to federal prison in 1943. In prison, she continued to help the less fortunate, especially young women who were jailed because they had taken up prostitution to help their families survive.

In 1948, she ran for vice president of the United States; Trotskyist Farrell Dobbs was her running mate. In 1952, after her father died, she returned to her Catholic faith and left the Socialist Workers Party, believing it conflicted with her Catholic beliefs. In 1964, she became one of the founders of St. Mary's Junior College in Minneapolis. Carlson began teaching, giving talks about the qualities of an educated woman and attending daily Mass.

In the 1960s, years after Carlson had returned to the church, she wrote letters to a priest friend in which she discussed her lack of support for new leftists like Thomas Merton and Daniel and Philip Berrigan who often publicly disagreed with the church hierarchy regarding the Vietnam War. They penned numerous spiritual insights in their books, poems and letters. Carlson thought their actions — pouring blood on draft files, for example — were overly-dramatic, immature and would eventually hurt their cause.

Advertisement

Haverty-Stack follows Carlson from her early childhood to her death. The book is roughly divided into three parts covering Carlson's formative years; her years as an activist for the Socialist Party during which she left the Catholic Church, separated from her husband, Gilbert Carlson and became romantically involved with Socialist Party leader Vincent Dunne; and her years after she broke up with Dunne, reunited with her husband and returned to Catholicism.

Although the middle section tends to drag somewhat, the first and final sections are deeply engaging. They focus on Carlson's life as a student in parochial schools and later as a faculty member and advocate for young working-class women.

Carlson herself was a member of the working class in Minnesota and inspired by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, the Josephites. These were the smart, educated and underpaid women who staffed the Minnesota schools — St. Vincent's Elementary School, St. Joseph's Academy and the College of St. Catherine, which Carlson attended. They served as models for professional women and influenced Carlson to earn her doctorate from the University of Minnesota, where she later taught.

Josephite schools emphasized the Gospel message of social justice, and Carlson took Jesus literally when he said that people must love their neighbors as they did themselves. Believing in the sanctity of all life, she ascribed to the tenets of Catholic action and emphasized the importance of helping the less fortunate.

The Josephites also taught Haverty-Stacke, who attended their schools in New York. From these nuns, as she acknowledges at the end of the book, she learned lessons about the value of work and education and the importance of serving others, values which have stayed with her and fueled her understanding of Carlson's life.

That understanding is evident in this biography even though it offers little insight into Carlson's private life, mostly because Carlson revealed almost nothing about her personal life in her talks, her letters and even in her interviews. Unfortunately, she did not share her inner feelings in an autobiography as her contemporary, Dorothy Day, did in The Long Loneliness.

We do know from this book that Carlson was appalled by the poverty that she saw around her in Frogtown, the neighborhood in St. Paul where she grew up with her mother, father who was a boilermaker for the Great Northern Railroad, sister and two uncles. Her uncle Casper was an adamant Socialist and shared Marxist newspapers with her. She was disturbed by the unfair treatment of workers and the poor working conditions they described.

But it was Mary Holmes, her mother, who arguably had the greatest impact on her life and character. Mary Holmes believed in the importance of education for everyone — not just for men as was common during the early 20th century. At that time, few women went to high school. let alone to college, and those few who did primarily learned to be good companions for men.

A German immigrant, Mary disagreed with prevailing opinions. She wanted Grace and her younger sister, Dorothy, who also joined the Socialist Workers Party, to have more out of life rather than falling into the patriarchal roles expected of women.

She believed her daughters should seek education as a way to develop their innate abilities. Through her example, they learned to love reading and writing and excelled in school. If it is true that there's a woman behind every successful person, Mary was the woman behind her daughters' accomplishments, as Haverty-Stack's informative account demonstrates.

Given Mary Holmes' lack of opportunity and the time in which she lived, that was an achievement in its own right. Ultimately, she taught both her daughters to be independent thinkers long before it was fashionable.