From left, Jottape as MC Doni and Christian Malheiros as Nando in an episode of "Sintonia" (Netflix/Vanessa Bumbeers)

The Brazilian Netflix original series "Sintonia," though a work of fiction, gives viewers a hopeful and insightful glimpse into the lives of those who live in the favelas of São Paulo.

Created by "funk" megaproducer KondZilla, the show portrays the inner workings of funk carioca and sheds light on why funk speaks to the hearts of people from Brazilian favelas to dance clubs around the world. This is all executed, however, in a way that gives little visibility to funk's initiators — Black Brazilians. The limited visibility of Black Brazilians further perpetuates the stereotyping and erasure of darker skinned women and men onscreen.

Now in its second season, the series features three childhood best friends growing up together in a favela in São Paulo. Nando is an orphan who turns to dealing drugs in order to provide for his family after he finds out his girlfriend is pregnant. Rita, also an orphan, converts to evangelical Christianity after getting in trouble for selling pawned goods. And Doni, the son of straightlaced, hard-working convenience store owners (who become parental figures to Rita and Nando), aspires to make it big in Brazil's funk scene.

"Sintonia" weaves together the stories of these three protagonists in a way that demonstrates the parallels between music, drug dealing and religion as a means to confront and escape poverty. Rita, who feels called to preach God's word after her run-in with the law, receives a sense of dignity from her newfound faith as well as a sense of belonging in her church community. Her adherence to biblical moral precepts also deters her from engaging in activities that were often dangerous and left her feeling degraded and depressed.

As much as Nando holds moral reservations about drug dealing, he decides it is the most effective way to provide for his girlfriend and daughter. He is careful not to let his massive earnings get to his head — he makes sure to save his excess earnings for his daughter's future and for family emergencies.

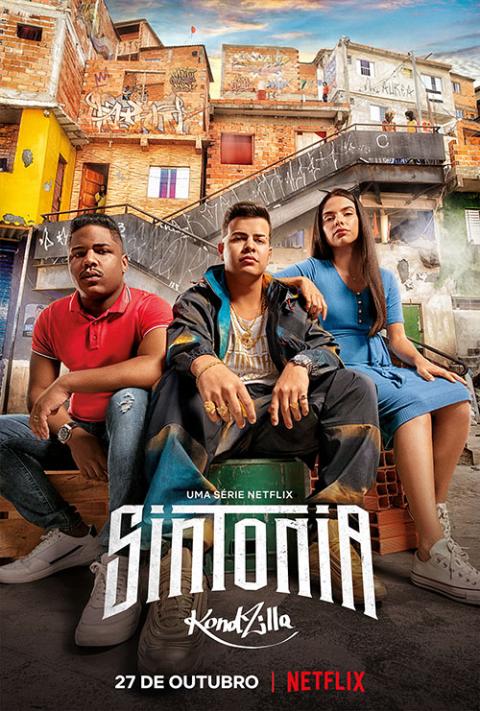

Poster art for the television series "Sintonia" (Netflix)

Doni begins singing informally in his parents' store and later starts singing in the neighborhood bailão, or dance balls, eventually getting noticed by more established funk MCs and record label executives. For Doni, singing is not only a means to make money and garner fame — he continuously proclaims that it is a way for him to bring joy and hope to others.

Though conflicts arise in their friendship, the three protagonists continue to support each other, whether by attending one of Rita's sermons or seeing Doni perform at a show.

Though they all have their own ways of confronting poverty, the series highlights funk music as a "best of both worlds": It is a means to make money and a means to seek existential meaning, thus encompassing the spiritual and financial pursuits of both Rita and Nando, respectively.

Funk music (also known as funk carioca, baile funk or favela funk) first emerged in the predominantly Black favelas of Rio de Janeiro in the 1980s. Residents would gather in the streets to hear DJs play what sounded like a mix of Miami bass, freestyle, hip hop and Candomblé, an Afrodiasporic religion that arose in Brazil in the 1800s.

Soon, MCs began rapping over the beats the DJs played. The songs focused on dancing, sex, poverty, violence and drugs. Though many condemned funk for glorifying misogyny and gang life, MCs and fans have asserted that it gives voice to the experiences of the most marginalized in Brazil, including the women and men of the favelas.

Funk carioca enjoyed some international recognition in the late 2000s, thanks to artists like M.I.A., who in 2004 released "Bucky Done Gun" inspired by Tigrona's funk carioca song "Injeção," and Major Lazer, who released "Pon De Floor" in 2009.

But it wasn't until the producer Konrad Dantas (KondZilla) launched his massively popular YouTube channel in 2017 that the popularity of funk started to explode across the world. Now the 14th most followed channel in the world with 65 million subscribers, CanalKondZilla launched the viral videos of artists like MC Fioti and MC Kevinho, which have each garnered more than 1 billion views.

KondZilla has received criticism, however, for whitewashing the genre whose origin is undeniably Afrodiasporic. The pioneers of funk like Cidinho & Doca and Bonde do Tigrão were Afro-Brazilian. If funk's DJs, MCs, audience and sonic quality were all predominantly Black, then why are the majority of artists and dancers on his channel predominantly of a lighter complexion?

From left, Christian Malheiros as Nando, Bruna Mascarenhas as Rita and Jottape as MC Doni in "Sintonia" (Netflix/Vanessa Bumbeers)

This lack of visibility of Black people in his work is also reflected in "Sintonia." Nando, the protagonist with the darkest complexion, is a drug dealer and the only other black recurring characters are MCs Dondoka and Luzi, who only show up in two episodes, and the twins, Rivaldo and Jaspion, who serve as MC Doni's goofy, fun-loving hairdressers and hypemen. Black characters in the show are either criminals (like Nando) or clownish jesters (like the twins).

Whitewashing is not unique to funk, existing all across the pop culture consumed from the Americas to Europe to Asia. Many creators in power, especially white ones, intentionally obscure the Black roots of artistic and cultural phenomena. For consumers, this ought to raise questions about how we are conditioned to conceive of the dignity and worth of certain humans as less relevant than others through our media.

Though the mainstreaming of funk has greatly whitewashed the genre, there is a growing amount of voices that are trying to bring visibility to the current and past funk artists of African descent.

Recife-based music journalist GG Albuquerque sheds light on how the Afrodiasporic roots of funk speak to both its sociological and metaphysical significance. Albuquerque claims that the philosophical underpinnings of Western humanism have only served to legitimize the dehumanization of non-Western peoples and delegitimize their spiritual and cultural contributions. "The idea of 'humanity or civilization' is precisely the ideological facade that legitimates the looting of precious metals in the Americas, the enslavement of black labor in Africa, and how Europeans know themselves: fully human — though, in the eyes of other peoples, not so fully — civilized versus savage, co-opting other peoples into already 'civilized' colonial models."

Though Albuquerque acknowledges that European Christianity's appropriation of post-Enlightenment Cartesian dualism served to rationalize their dehumanization of black bodies in the slave trade, his Afroperspectivist, incorporated philosophy restores the theological significance of the Incarnation, and thus sheds light on the connection between Afrodiasporic music forms like funk and Christian spirituality.

Advertisement

"We must look at this artistic production" of Afrodiasporic artforms like funk and samba "as a transformative, potent, and inherently subversive philosophical discourse," Albuquerque says. "As the most disruptive and defiant art, blackness is always a question, never an answer. ... Black music in contemporary Brazil ... seeks to conjure and to institute new modes of creation, life, and happiness. The dream is of a world in which the fundamental racial oppression of modernity and its idea of civilization and rationality are surpassed."

He goes on to cite the writer Kyra Gaunt, who highlights how the African drumming patterns used in funk demonstrates the body's ability to speak truth: "The body is a technology of black musical communication and identity. ... The social body as a tool or method of artistic composition and performance, however, continues to be overlooked in the study of music, just as the black vernacular body continues to be overlooked in dance history. Drums or any other forms of musical 'technology' are but extensions of things the body and voice can do. The striking of body parts and cavities, the resonating of the singing voice, and use of verbal and nonverbal language, manufactured codes, identifications, and ideas about music and life through the 'systematic' (re)production of an embodied phenomenology."

Through its exploration of sexuality, dancing, partying and social injustice, and its pulsating percussion, funk speaks to the desire for liberation and happiness inherent to all human beings. And while it downplays funk's Afrodiasporic roots, "Sintonia'' reminds us that our search for God is not only a matter of the mind or spirit, but that it encompasses our whole being, including our bodies.

Pope St. John Paul II wrote in an address on the theology of the body: "The fact that theology also considers the body should not astonish or surprise anyone who is aware of the mystery and reality of the Incarnation. ... Through the fact that the Word of God became flesh, the body entered theology through the main door."

Funk should especially speak powerfully to Christians who believe in a God that communicated the truth of his being not only through words, but through bodily gestures like walking, weeping, eating and singing and dancing.