Pope Francis receives his ring from Cardinal Angelo Sodano, dean of the College of Cardinals, during his inaugural Mass in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican March 19, 2013. "Let us never forget that authentic power is service," Francis said at the Mass. The pope "must be inspired by the lowly, concrete and faithful service which marked St. Joseph," he said. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Editor's Note: This is a condensed version of an address Austen Ivereigh gave May 25 to the Union of Superiors General, the Rome-based umbrella group representing male Catholic religious orders across the world. NCR is publishing the address with Ivereigh's permission.

In November 2003, during the high noon of Cardinal Angelo Sodano's iron-fisted rule as John Paul II's secretary of state, a Mexican friar wrote for a Chilean journal an article that was passed across the world's Catholic networks in open-mouthed amazement.

As deputy editor at the London-based Catholic weekly The Tablet it was my job to edit and translate the article, entitled "Violence in the Church." Few at that time dared to speak like this. It felt like being passed a sizzling stick of dynamite.

"To speak of violence in the Church might seem nonsensical," began Fr. Camilo Maccise, a Discalced Carmelite who had only recently ended his term as head of the Union of Superiors General, or USG, in Rome. Violence, after all, involves coercion — physical, moral, psychological — to impose one's will. Jesus came to free us from slavery and oppression and built his church on love of God and neighbor. Authority in the church is service: ministerium, not potestas. It is incompatible with violence.

And yet, as superior general of the Discalced Carmelites for two six-year terms and USG president in the late 1990s, "violence of a moral and psychological character" is what Maccise had experienced firsthand. "I have had had intimate knowledge of this violence, above all as exercised by a number of Roman dicasteries," he wrote, before going on to describe the ways in which that "violence" was exercised: in centralism, authoritarianism and dogmatism.

Pope John Paul II receives ashes from Cardinal Angelo Sodano during the Ash Wednesday liturgy at St. Peter's Basilica Feb. 25, 2004. Sodano, who died May 27 at age 94, served as John Paul II's secretary of state 1991-2006 and dean of the College of Cardinals 2005-2019. His legacy was tarnished by his support for Fr. Marcial Maciel, the serial sexual abuser and founder of the Legion of Christ. (CNS/Reuters)

Sodano died in Rome on May 27 at age 94, just days before the implementation on June 5 of Pope Francis' new constitution for the Roman Curia, Praedicate Evangelium ("Preach the Gospel"). The constitution consolidates and deepens the reform that Francis has been carrying out these past nine years. It is a reform aimed at nothing less than a conversion of the way power is exercised in and from Rome, and by extension in the global Catholic Church.

To understand that conversion, you have to put Praedicate alongside the Maccise article, to see how the first responds to the second. What Maccise dared to say aloud in 2003 was what the cardinals at the pre-conclave meetings 10 years later stood up one after the other to deplore. The reform was "strongly wished for by most of the cardinals gathered in the pre-conclave general congregations" in March 2013, as Praedicate itself recalls. Among those who made a series of proposals for reform was Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the future Francis, not imagining that he would be the one carrying them out.

Exactly nine years later his apostolic constitution was released March 19, the Feast of St Joseph, the anniversary of the inaugural Mass of the pontificate. The new pope's homily at that Mass spoke of authentic power as being that which serves by protecting both creation and creatures. It is a gentle, holy power, because it cooperates with divine power. It is the power the church should depend on.

The shift to that power in Francis's apostolic constitution is clear even from its title. The subtitle of John Paul II's 1998 constitution, Pastor Bonus, is "Apostolic Constitution of the Roman Curia." Praedicate significantly adds: "and its service to the Church in the world."

The days of anonymous denunciations and heresy trials are long gone.

Back in 2003, Maccise described how curial power was concentrated in central bodies remote from the lives of believers who are seen as children in need of protection or correction. Key to centralism was the way the Curia wedged itself between the pope and the wider church, using the vicarious power of the papacy to browbeat bishops, who according to the Vatican II doctrine of collegiality, governed the church with the pope yet were treated on their ad limina visits — they often said — like altar boys. Similarly, the USG and the International Union of Superiors General, representing over a million religious worldwide, were after 1995 until his death blocked by suspicious curial officials from ever meeting with John Paul II.

Praedicate says clearly that the Curia "does not place itself between the Pope and the bishops, but is at the full service of both." Six articles (38-43) are dedicated to the ad limina visits, placing great importance on them, and stressing the role of the Curia in facilitating them, in encouragement and dialogue. This has long happened under Francis: Bishops who remember the old ways are astonished at dicasteries now asking, "how can we help?" and at the free-flowing two-hour meetings with the pope in which anything and everything is on the table. The meetings of religious with Francis are now so regular as not to be news.

U.S. cardinals listen as Pope John Paul II addresses the special summit on clergy sexual abuse at the Vatican April 23, 2002. Cardinal Angelo Sodano, then Vatican secretary of state, is seated facing left of the pope. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Maccise in 2003 indicted the way documents flooded out of the Vatican that touched directly on the lives of the faithful yet who were never consulted in their drafting: Not one of the 775 convents of the Discalced Carmelites was consulted during the preparation of Verbi Sponsa, the 1999 document on contemplative life and enclosure. Sodano's Curia also exercised "habitual forms of authoritarian violence": using anonymous delations (accusations) to Rome to denounce "heterodox" people, and famously hounding theologians accused of heresy by curial officials who cloaked themselves in sacred power.

Among these "habitual forms" of violence, Maccise wrote, was "a dogmatism that refuses to admit that in a pluralist world it is not possible to impose single religious, cultural and theological standpoints," confusing what is essential in doctrine and its relative theological expressions. The Maccise article also called out the attempt to eliminate tensions and conflicts in the church by suppressing dialogue, creating a climate of fear that permitted a rigid uniformity to be imposed in the name of a false idea of unity.

Francis' Curia is barely recognizable from this description. Vatican documents, vastly reduced in number, are (generally) these days the fruit of painstaking and lengthy consultations. The days of anonymous denunciations and heresy trials are long gone.

So, too, has the illusion of creating unity by quelling "dissent:" Catholics are learning to live in a polyhydric synodal church that listens, dialogues and holds together differences in tension in expectation of resolution by discernment. Authority is still in charge, but takes decisions after many have been involved in their making.

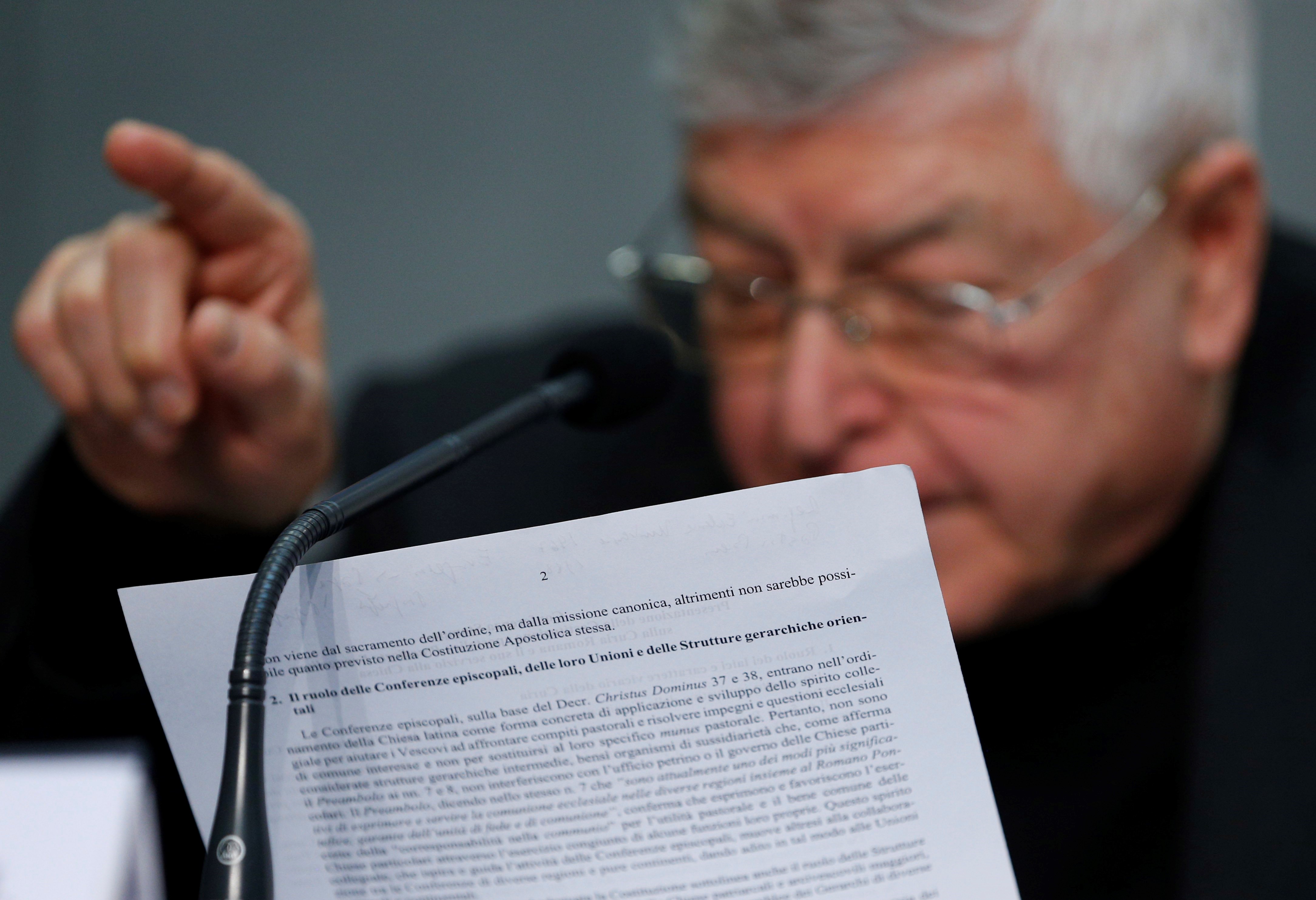

Jesuit Fr. Gianfranco Ghirlanda, a canon lawyer and former rector of Rome's Pontifical Gregorian University, speaks at a news conference to present Pope Francis' document, "Praedicate Evangelium" ("Preach the Gospel"), for the reform of the Roman Curia, during a news conference at the Vatican March 21. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Nor is authority tied any longer per se to sacred orders. One of the key brains behind Praedicate is the Jesuit canonist, cardinal-designate Gianfranco Ghirlanda, who says the new constitution clarifies and confirms that "the power of governance in the Church does not come from the sacrament of Orders, but from the canonical mission." This means that religious brothers and sisters, or laypeople, can head dicasteries. Francis also intends that future dicastery heads will not be cardinals, to break that link also.

To see this as "lay empowerment" is to miss the bigger point. It might equally be a priest or a nun or a bishop who heads a dicastery. The point is to allow a church in which leadership is tied to charisms and ministries, rather than bound up with the clerical state and ecclesiastical careerism. What this implies is a synodal church in which communion is the fruit of a mutual listening, in which people of faith, bishops, the Bishop of Rome are each listening to the other, and all listening to the Holy Spirit.

As Francis says in Evangelii Gaudium, summing up the Second Vatican Council: "in all the baptized, from first to last, the sanctifying power of the Spirit is at work. … God furnishes the totality of the faithful with an instinct of faith — sensus fidei — which helps them to discern what is truly of God." The tradition of the church is passed down through the faith of the people, which the bishops interpret, with the pope acting as the final interpreter and witness, the discerner-in-chief, who teaches the faith not on the basis of his personal convictions but witnessing to the faith of the whole church.

Pope Francis leads a meeting with cardinals, bishops, priests, religious and laypeople from around the world in the Synod Hall at the Vatican Oct. 9, 2021. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Authority in the church, in other words, is spiritual, and bottom-up. It rests on processes that discover the Spirit's will. It is to take seriously what Jesus promises in the Gospel of John: that the Spirit will guide us, strengthen us, teach us, bring us peace, so that we need not be fearful or anxious. We will have no need of authoritarianism, coercion and control, because it is not our power we rely on, but God's.

That is why the conversion of power under Francis goes far deeper than new structures and processes, important as they are. "What really matters," the pope writes in his prologue to a recent Spanish book interview on the making of Praedicate, "is the renewal of people's hearts and minds."

It is about whether we trust grace, or whether — enter, at this point, our old friend Pelagius — we trust in our own means.

Advertisement

Consider Pastor Bonus. John Paul II's constitution focused in almost every paragraph of its introduction on the preserving unity of faith and discipline. Communion is identical with unity, which is "a precious treasure to be preserved, defended, protected and promoted." The agent of this preservation is the Curia, handed juridical power to achieve this. It is easier to see why, on this understanding, the Curia believed it was acting righteously ("preserving unity") when it berated bishops, prosecuted theologians or barred the USG from contact with the pope.

In Praedicate, by contrast, the church's purpose is spelled out as the mission of witnessing in word and deed the mercy she has received. This mission is entrusted to the whole People of God. The church witnesses to this mercy by its communion, which is not forged by any human agency but is a gift of the Spirit that flows from the mutual prayerful listening of faithful people, bishops and the pope.

The shift here is of agency. Communion is not the object of the Curia's efforts but the gift of the Spirit received by a synodal church. The Curia is not the source of this gift but a key agent of its reception, promoting an exchange of gifts through its service to both the pope and the local churches. It is service that performs the good Samaritan, in which Christ is recognized in the face of all, especially of the weakest and most vulnerable.

Pope Francis leads a prayer as he appears for the first time on the central balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican March 13, 2013. At the pre-conclave meetings before Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected pope, cardinals expressed the desire for church reform. (CNS/Paul Haring)

"There can exist and there does exist a Gospel style of exercising authority," Maccise wrote in the 2003 article that led to his being hounded by Sodano's Curia and dismissed as a communist troublemaker.

Maccise and Bergoglio knew each other and had worked together at the synod on religious life back in the 1990s. The Carmelite died in Mexico City age 74, of cancer, in 2012, just before his friend and fellow Latin American religious became pope, and set about embedding that very Gospel style of authority in, of all places, the Roman Curia.

At the end of August, Francis is calling together the world's cardinals for a two-day study of Praedicate. I've done it, he can tell them, and here it is. Go, and do likewise — so that maybe one day we can all say it is indeed nonsensical to speak of violence in the church.