Women sing during a Mass for solidarity and peace Aug. 24, 2017, at St. James Cathedral Basilica in Brooklyn, New York. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Women have been the backbone of the Catholic Church in the U.S. and other Western countries since at least the beginning of the 20th century. Despite disagreeing with various elements of church teaching, they have long maintained a higher degree of participation than men have in the church's sacramental and communal life, and have also been instrumental in keeping men within the fold.

The resilience of their commitment to Catholicism, however, has come into question in recent years. When my colleagues and I, in American Catholics in Transition, analyzed the findings from our fifth national survey of Catholics conducted in 2011, we were struck by the steady pattern of decline in women's commitment observable over the prior 25 years. Now, with data in hand from our sixth national survey of Catholics, which we conducted in April 2017, it is opportune to assess where Catholic women stand in terms of their commitment to Catholicism.

A six-year interval is a relatively short span for assessing change. But a lot has happened in the church in that time. The historically unprecedented papal transition in 2013, with Pope Benedict XVI resigning and Pope Francis elected his successor, has given rise to an array of developments impacting the character of Catholicism, notwithstanding some ambiguities and unevenness.

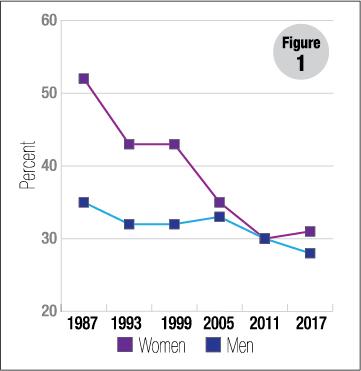

Figure 1: Weekly Mass attendance by gender

Our survey was not designed to explore any "Francis effect" on American Catholics — and indeed any study with that intent would be very complex and difficult to execute. But four years into Francis' papacy, our survey's replication of questions asked of American Catholics at previous intervals can help pinpoint new trends that may be coincidental with his tenure.

In the case of women's commitment, the overall story is one of stability, and even slightly increased commitment, rather than further decline. Catholic women's weekly Mass attendance has stabilized. In 2011, continuing a pattern of sharp decline from the late 1980s, 31 percent of women went to Mass weekly, and a similar proportion reported weekly Mass in 2017 (see Figure 1). Today, women are just slightly more likely than men to go to Mass at least weekly.

On two other indicators of commitment, women show more of an uptick since 2011.

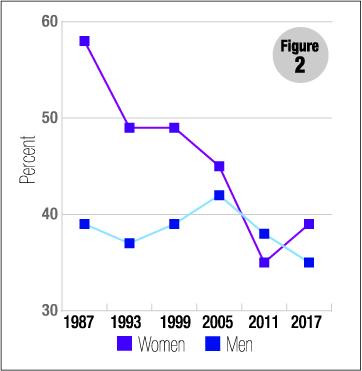

Figure 2: Catholic women and men who say the church is among the most important parts of their life

Figure 2 shows an increase in the proportion of women who say that the church is among the most important things in their life, from 35 percent in 2011 to 39 percent today. This finding is a reversal of the steady long-term trend of decline in the church's importance to women. Until 2011, the church had consistently been less important to men, and its level of importance remains remarkably steady. Part of the surprise in 2011 was the discovery that for the first time in 25 years, fewer women than men were saying that the church was among the most important parts of their life. With the 2017 data, women are once again more likely than men to regard the church as among the most important parts of their life.

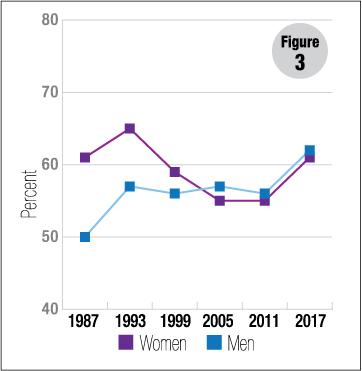

Catholics' views about whether they might leave the church tend to be somewhat fluid. As Figure 3 shows, while the early 1990s saw an increase in the proportions of women and men who said they would never leave the church, this view subsequently dampened. And since 2005, women's enthusiasm for staying has been largely on a par with men's, thus neutralizing what had been their relatively greater loyalty to the church. This gender convergence continues. And, importantly, it is accompanied by an increase since 2011 in the proportions of both women (from 55 to 60 percent) and men (from 56 to 62 percent) who say they would never leave.

Figure 3: Catholic women and men who say they would never leave the church

The findings presented here convey that American Catholics, women especially, are slightly more enthusiastic about being Catholic than Catholics in 2011 were. It is quite probable that Francis' papacy accounts for some of this renewed enthusiasm. Indeed, more than eight in 10 Catholic women (86 percent) and men (83 percent) express satisfaction with his leadership. And a larger proportion of women (62 percent) than men (53 percent) say they are "very satisfied." By contrast, and consistent with past surveys, just over a fourth (of women and men) are "very satisfied" with the leadership of their local bishop, and even fewer, less than a fifth, are "very satisfied" with the U.S. bishops' leadership overall.

While not diminishing the significance of Francis in renewing Catholics' interest or pride in the church, it is also important to keep in mind the relevance of other forces. In particular, it may be important to consider the possible cultural impact of the ever-growing increase in religious non-affiliation in the U.S. One in four Americans today have no religious affiliation. Although the trend has been steadily increasing since the mid-1990s, its continuing momentum — such as an increase of 5 percentage points in the proportion unaffiliated since 2012 — may have the effect of nudging those who continue to self-identify with a religious denomination to express a more tenacious hold on that identity.

It is interesting in this regard that Catholic women, for example, are not increasing their practice of Catholicism such as weekly Mass attendance (though neither are they reducing it). But they are expressing an increased attachment to Catholicism, as evidenced by their views of the church's importance in their life and the likelihood of staying in the church.

In the context of the overrepresentation of millennials in the ranks of religiously unaffiliated Americans, it's important to note that young adult Catholics, those born since 1979, appear less attached than older cohorts to the church. Just one in five (21 percent) attend weekly Mass, for example (compared to a third for Catholics overall). With regard to the importance of the church in their lives, there is not much variation between them and those born just one generation earlier (post-Vatican II Catholics born between 1961 and 1978). Yet, millennials are significantly less likely than older Catholics to say they would never leave the church.

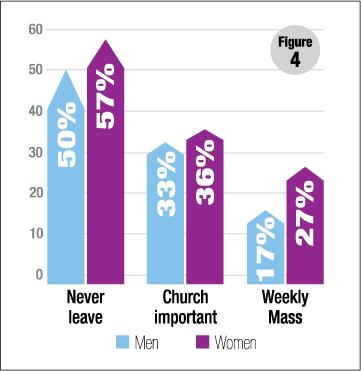

Among millennial Catholics, however, the traditional pattern of women's comparatively greater commitment seems to hold. In particular, they have a higher rate of weekly Mass attendance and are more likely than men to say that they would never leave the church (see Figure 4). Moreover, while older Catholics (64 percent) overall are more likely than younger cohorts (52 percent) to report being very satisfied with Francis' leadership, a much larger proportion of millennial women (62 percent) than men (42 percent) are very satisfied with his leadership.

Figure 4: Gender differences in church commitment among millennial Catholics, 2017

The evidence of a stabilization or reversal in women's declining commitment to the church is newsworthy. But it requires further study before any conclusion is drawn as to its antecedent causes. Further, only time — and data from successive years — will tell whether the patterns discussed here constitute a new turning point or merely a one-off spike.

Commitment to the church and strongly favorable views of the pope should not be equated with deference to the church's teaching authority. Since at least the late 1970s, American Catholics, women and men, have consistently disagreed with various elements of church teaching on sexual morality and other issues while simultaneously maintaining loyalty to the church. This dynamic has not changed, and is unlikely to change. Regardless of who's pope, American Catholics are Catholic on their own terms.

[Michele Dillon is Class of 1944 professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire. The views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of the University of New Hampshire. Her email address is Michele.dillon@unh.edu or follow her on Twitter @MicheleDillon15]

Advertisement