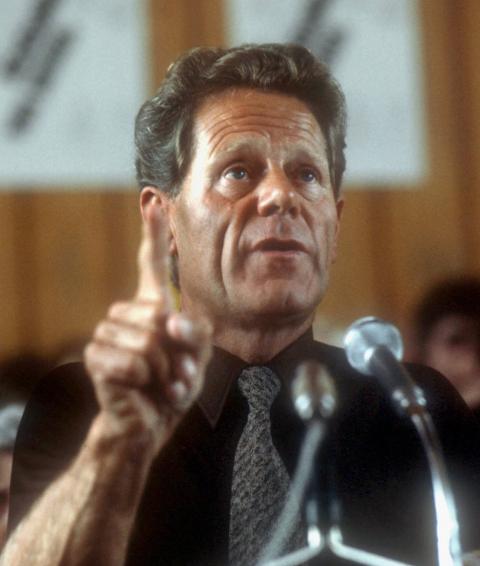

Swiss-born Fr. Hans Küng, a prominent and sometimes controversial theologian who taught in Germany, died April 6, 2021, at age 93. He is pictured here in 1980. (CNS/KNA/Hans Knapp)

Swiss-born Fr. Hans Küng, a prominent and sometimes controversial theologian who taught in Germany, died April 6, 2021, at age 93. He is pictured here in 1980. (CNS/KNA/Hans Knapp)

I am grateful for Hans Küng for his stellar contributions to theology and to the life of the Catholic Church. But I am even more grateful for the pastoral ministry he showed me in a time of need.

I was never a close friend of his, but we obviously knew one another, and our paths crossed occasionally. I first met him in person in Washington in 1968. Küng was in a town for a talk. A colleague of mine at Catholic University and friend of Küng's invited me to a 40th birthday luncheon in his honor. I reminded Küng at that time that we had a saying in the United States that you could never trust anyone who is over 40!

When Küng was declared by the Vatican not to be a Catholic theologian in 1979, Leonard Swidler of Temple University, David Tracy of the University of Chicago and I put together a very short statement quickly signed by more than 60 theologians simply saying that Hans Küng was a responsible Catholic theologian.

Over the years, as a junior colleague, I learned much from his multitudinous writings. (I do not know of anyone who was ever able to even read all that he had written.) As to be expected, I had some theological disagreements with him, especially his insistence that the teaching condemning artificial contraception was an infallible teaching.

In March 1986, the Vatican declared that if I did not change my positions on accepting artificial contraception for spouses and other moral issues, I could not exercise the function of a Catholic theologian. Küng contacted me, indicating that he was coming to New York for a talk but could fly down the next morning and have lunch with me before he flew back to Germany in the late afternoon. He wanted to help me by sharing with me his reactions to the Vatican declaration that he was not a Catholic theologian.

I was amazed and most grateful for his offer to come to Washington and talk with me. He obviously was going out of his way and interrupting his very busy schedule. He could have just written a note of support, but he wanted to do much more than that. When I put him on the plane to return to Germany, he would finally arrive back in Tübingen after an overnight flight only an hour before his scheduled seminar with doctoral students.

Advertisement

My meeting and lunch with him even exceeded my expectations. Küng reiterated that he wanted to talk with me about my situation and share some of his insights as the first contemporary Catholic theologian who had been declared by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith with the approval of the pope that he could no longer be considered a Catholic theologian.

He was obviously deeply hurt by the action taken against him and commiserated with me, but he strongly urged me to continue my theological work. There was a need for me to carry on my writing in moral theology and work for renewal in the church. He assured me I would find support from many others in the church despite the action taken against me by the pope. No one has written more on the church and the need for continual reform in the church than Küng, but he was not there to lecture or teach me, but only to assist me as I grappled with my future.

It was necessary for me to continue the work of church reform. He shared with me his anguish at what was happening in the church. It appeared that the Vatican itself had betrayed Vatican II. Many people within and without the Catholic Church had given up hope that anything decisive could take place behind the walls of the Vatican. But Küng did not share this pessimism. The voices from below in the Catholic Church must continue to speak.

Hans also shared with me on a personal note. What had bothered him the most in his own struggle was the failure of some who he considered to be friends who did not support him. He was comforted and strengthened, however, by the support of many, but he could not forget what he thought was a betrayal by others.

Hans Küng has been the strongest voice for reform in the Catholic Church during the last 60 years. It was in 1961, a year before Vatican II began, that he published The Council, Reform and Reunion in a number of different languages. The book called for a broad-based reform of the Catholic Church and pointed toward the goal of the reunion of all Christians. In the 1960s, he frequently lectured before large audiences here in the United States. His lectures were not the dry reading of a text that was typical of German professors, but a dynamic, electric and personal presentation enhanced by his ability to respond clearly to questions. In later years, his writings extended to many topics outside of traditional theological concerns, including dialogue with other religions and his work on global ethics.

Like many, I learned from his many and varied writings, but above all, I am grateful for a side of Hans Küng that many did not experience — his willingness to go out of his way to minister to and encourage me in my need.

May he rest in peace.