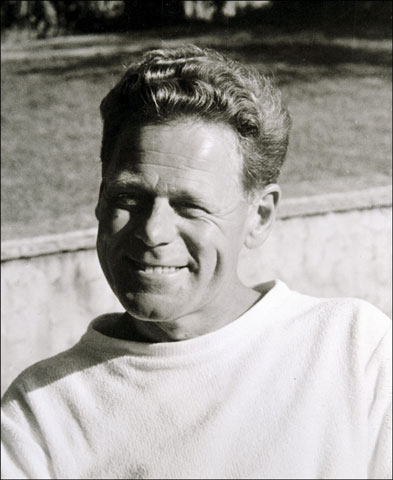

Fr. Hans Küng (Newscom/Album/sfgp)

Note from Jamie Manson, NCR books editor: Swiss theologian Hans Küng has written more than 70 books that have influenced not only the ongoing quest to reform the Catholic church, but also theologians and practitioners who engage in ecumenical theology and interfaith dialogue. We asked noted scholar Leonard Swidler and veteran journalist John Wilkins to guide us in our appreciation of the vast scope of his corpus. Not only are Swidler and Wilkins experts in Küng's thought, both have read the third and final volume of Küng's memoir, which has yet to be translated from the original German. Both retrospectives also offer reflections on his latest title, Can We Save the Catholic Church?/We Can Save the Catholic Church! (William Collins, $16.99) Today, we offer Swidler's reflection; Wilkins' will run Friday. Both ran in the April 28-May 8, 2014, edition of NCR.

There are a number of reasons why it is particularly apt that I would be writing about theologian Fr. Hans Küng's latest writings. To begin, we are both 85 years old -- one year younger than that of a former colleague of ours on the Catholic theological faculty of the University of Tübingen, Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. Secondly, I was at Tübingen even before Hans in the late 1950s, as a student working on my doctorate in history from the University of Wisconsin, and my Licentiate of Sacred Theology from the University of Tübingen.

I arrived in Tübingen, Germany, in the fall of 1957. During the summer semester of 1958, I attended an interesting course offered by the Protestant theology faculty on a newly published book that compared the doctrine of justification according to 20th-century Swiss Protestant theologian Karl Barth with the doctrine of the 16th-century Catholic Council of Trent. The book dramatically concluded that they were essentially the same.

The author was a brash newcomer on the exciting theological scene, the young Swiss Catholic Hans Küng. I didn't know who he was then, nor did hardly anyone else -- except Ratzinger, who was a fellow assistant to Professor Hermann Volk of the Catholic theology faculty of the University of Münster. It was the same Volk who, as cardinal archbishop of Mainz, Germany, grilled Hans about his best-seller On Being a Christian. At one point, Volk blurted out: "Herr Küng, Ihr Buch ist mir zu plausibel!" ("Mr. Küng, your book is too plausible!")

Hans and I first "met" when he, as the successor at Tübingen to my doctoral adviser, Heinrich Fries, wrote to me at the University of Munich, where I was continuing my research, about the publication of my Tübingen thesis. A year later, after I was ensconced in the history department of Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, I invited him to come as a visiting theology professor.

At that point, the excitement over the forthcoming Second Vatican Council (1962-65) was beginning to heat up, and soon the English translation of his book The Council, Reform, and Reunion catapulted Hans to the status of a theological rock star.

He soon made a triumphant lecture tour of the U.S., including Duquesne, where the largest hall was sold out two weeks beforehand. Hundreds more were put into a neighboring hall, where the lecture was piped in. Hans told me that he subsequently had so many offers of professorships -- starting with Harvard -- that he felt he had to turn down my invitation, along with all the others.

It was in the midst of the frenetic excitement of the council that my wife, Arlene Anderson Swidler, came up with the idea of filling a then-gaping hole in theological scholarship, and we launched a scholarly periodical devoted to ecumenical dialogue: the Journal of Ecumenical Studies. We gathered a key group of associate editors, including Markus Barth (one of Karl Barth's sons) and Hans Küng. The first issue in 1964 (50 years ago this year) contained articles by two young periti at Vatican II, which was reaching its crescendo by then: Küng and Ratzinger. For Hans, Arlene and me, this was just the beginning of a more than half-century-long friendship and collaboration on innumerable projects.

It is through the lens of our long relationship that I read Volume 3 of Hans' memoirs.

It is vintage Küng. Hans must have -- with German-Swiss clockwork -- saved and carefully filed every paper and note he took on his myriad travels, meetings, conferences and conversations. All is carefully documented, not in a pedantic manner, but in a way that assures the reader that she or he is getting wie es eigentlich gewesen, or what really happened.

So many of the world's thinkers and doers came to Hans, or he to them, that this third, and presumably last, volume of memoirs reads much like an intellectual, cultural and political "who's who" of the late 20th and early 21st century. Hans obviously wrote right up until the printer pulled the paper out of his hand to finish the book, for he recorded that on June 28, 2013, he wrote to Pope Francis asking for permission to reproduce the warm, handwritten note Francis had written to him in Spanish. (He clearly received an affirmative response.)

Hans means to make this volume his vaya con Dios in the sense that, at the end, he looks back and reflects on what he judges is a full and complete life. He said goodbye to his lifelong weeks of skiing -- "one of the most fascinating sports" -- in his beloved Swiss Alps as of 2010. He speaks of his various health issues and countering exercises.

The title of the mere 350-page English-language book, Can We Save the Catholic Church?/We Can Save the Catholic Church!, says it all. The second half of the English title is not in the original German (which was Ist die Kirche noch zu retten? -- "Can the Church Still Be Saved?"), but it echoes a sentiment that can be found in all seven chapters of the book. Küng sees long-term history moving through an ongoing series of lesser and larger paradigm shifts that are always resisted until a tipping point is reached and the new paradigm takes the center of thought and action.

He is convinced -- as I am, as well -- that we are in the midst of a major paradigm shift that, expectedly, is vehemently resisted. Nevertheless, it is replacing the old -- in this case, the Catholic medieval/Counter Reformation -- paradigm.

It is interesting and encouraging to read that last summer, when Hans sent a note of greeting and a Spanish copy of this book to Francis (and to the cardinals on the new papal Council of Cardinals, each in his own language), in only a few days he received the handwritten card mentioned above. In it, Francis thanked Hans for his note and the book, which, he said, he would read with pleasure.

Hans obviously knows intimately more about the deep problems of the past and present Catholic church than anyone else alive today, and he distills these structural, deadly flaws with scorching clarity. However, he doesn't simply criticize. He also lays out a set of suggested action plans. Hans, and now his readers, sees the depth of the disease in each portion of the church. But, learning the lessons of history, he knows that change is not only possible, but also inevitable.

Further, Hans also provides grounds for the inner courage that is needed to begin, or continue, those efforts, which will accelerate that positive change in the Catholic church. It is a vision of the church to which Hans, like so many others, has devoted, and will continue to devote, his life.

[Leonard J. Swidler is professor of Catholic thought and interreligious dialogue at Temple University, Pennsylvania.]