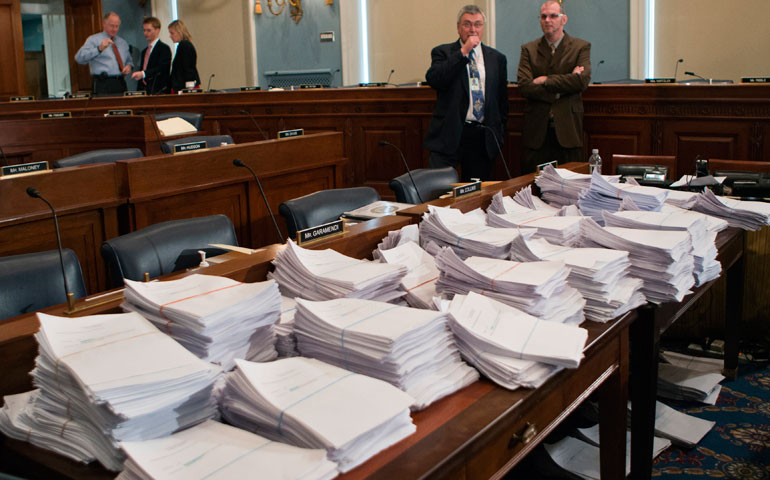

Stacks of paperwork await members of the House Agriculture Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington May 15, as it met to consider proposals to the 2013 farm bill. (AP/J. Scott Applewhite)

As Congress began its annual Fourth of July recess, members left the capital with a host of urgent national issues unresolved: immigration reform, the farm bill, and the long-sought, steadfastly evasive "grand bargain" of a budget.

It is fitting that Congress contemplate these issues on this holiday in particular because, at their deepest level, the politics of all three issues entail fundamental debates about what America is and what it should be. The Founding Fathers gave the nation a Constitution, but that Constitution leaves most of the hard decisions up to the people, and the people of the United States have rarely been so ideologically divided.

In mid-June, the farm bill failed to secure passage in the House when Democrats abandoned their support in the face of $20 billion in cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called food stamps) and conservative Republicans refused to support the bill because the cuts were not deeper.

"Last week's 'farm bill fail' in the House confirms what many Congress-watchers have long feared: Our legislative branch is dangerously incapable of governing," said Matt Green, an expert on Congress at The Catholic University of America in Washington. "There are plenty of reasons for this dysfunction, but the biggest problem, as I see it, is House Republicans. It's not just that they are ideologically divided. Too many of them are afraid of, or detest, the idea of compromise. And the party's leaders seem unable to even count votes, let alone lead."

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops lobbied hard for preventing the cuts to SNAP. "The farm bill is essential legislation that determines our country's food and agriculture policy," said Kathy Saile, director of domestic policy at the bishops' conference. "It is the road map for how our country treats hungry people at home and abroad." For years, the farm bill has enjoyed wide bipartisan support, with rural Republican representatives backing its subsidies for farmers and liberal Democrats backing the food stamp program.

Green cites two reasons why the demise of the farm bill bodes ill for other issues like immigration reform. "The first was that Republican leaders were caught off-guard. Rule No. 1 for a majority party is to only hold votes when you know the likely outcome. That's a rookie mistake, and leaders who want to enact something as delicate as immigration reform can't afford to make rookie errors," Green said. "The second thing that struck me was the number of Republicans who voted for an amendment to make the bill more conservative, yet still voted against the final bill. It was, in retrospect, a wasted effort of party leaders to support that amendment."

The politics of immigration reform are different from other issues, however. Individual Republican members of Congress may feel the need to oppose any bill that grants a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. But they may also realize that if they block immigration reform, no Republican will win the White House in the near future. Last year, Barack Obama took 71 percent of the Latino vote to Mitt Romney's 27 percent, and Latinos are the fastest-growing demographic in the electorate. If the 2012 electorate had the racial characteristics of the 2000 electorate, Romney probably could have won. In 2016, the electorate will include even more Latinos and other minorities, not fewer.

Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, who is Catholic, will ultimately decide if he wants to bring an immigration bill to the floor even if it lacks the support of a majority of his caucus. "What will matter is not how many Republican votes [Boehner] gets but whether a majority of his caucus quietly decides that passing immigration reform is better for the party than blocking it is," E.J. Dionne wrote in The Washington Post. "Many in such a majority might actually vote against a bill they privately want to see enacted. By doing so, they could satisfy their base voters back home while getting the immigration issue off the political agenda and ending the GOP's cold war with Latino voters." Republican House members could avoid facing a primary challenge from their right because they vote against reform, while allowing Boehner to pass it with mostly Democratic votes could save the GOP's chances in national elections, too.

Still, in these ideologically driven times, that will not be an easy sell. "Maybe immigration reform will have a stronger lobby behind it than the farm bill did," Green said. "But immigration is also a highly sensitive political issue, and one that deeply divides the GOP. Unless Speaker Boehner can find a new recipe for leadership on these other bills, I fear the present House will continue to marginalize itself."

Looming on the horizon is yet another fiscal cliff as the U.S. Treasury approaches the need to get a congressional extension of its borrowing authority this autumn. Two years ago, Congress came within days of a first-ever default on the national debt, the consequences of which could be catastrophic for the world economy because U.S. Treasury bonds are always considered the safest of havens for investors. If Congress cannot come together to pass the farm bill, and if only the most calculating of political strategies might get immigration reform through the House, cutting a "grand bargain" budget deal with the Obama White House is probably a bridge too far for Boehner. And, because the estimates of the current deficit have been plummeting, the pressure to tackle the long-term debt issues facing the country are less immediate and, just so, less likely to stimulate any impetus toward compromise.

On all three issues -- the farm bill, immigration reform and solving the government's long-term finances -- the underlying issue is what kind of country America will become. American politics has normally been relatively non-ideological, with the Republicans championing the interests of business and Democrats championing the interests of those whose social and political objectives were unaddressed by business, a dynamic that goes back at least to the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Defending interests, as opposed to ideologies, has allowed both parties to achieve compromise.

Most recent presidencies witnessed a fairly high degree of collaboration between the parties, with Ronald Reagan working with Democrats in Congress to overhaul the tax code, George H.W. Bush pushing the Americans with Disabilities Act, Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich enacting welfare reform, and George W. Bush working with Ted Kennedy to pass No Child Left Behind and Medicare Part D.

The election of Obama in 2008 served as an ideological lightning rod for many Americans. "The tea party has turned a once responsible Republican Party into an economically illiterate and politically irresponsible anti-government group of zealots," said Fred Rotondaro, chairman of Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good. "They are hurting Americans now and destroying the true concept of American exceptionalism."

Rotondaro said he believes America's exceptionalism is found in its immigrant history and its blending of private and public sector activity on behalf of the common good.

Conservatives, of course, see American exceptionalism differently. They think government is the problem, as Reagan famously said, a catchy line he ignored in governing. In a recent book, Becoming Europe: Economic Decline, Culture, and How America Can Avoid a European Future, Samuel Gregg of the conservative Acton Institute wrote, "To a good number of Americans, the bailout of banks, Congress's apparently insatiable appetite for spending, the passing of Obamacare into law, the new regulatory regime for the financial industry, and the government's rescue of American car companies increasingly looked like a wider pattern. Something seemed to be changing -- and not for the better -- in American economic and political life."

Millions of Americans, however, saw signs of hope in the prospect of finally having health insurance, of knowing that their life savings would be better protected from Wall Street speculators, and of seeing that autoworkers were not losing their jobs. All three policies embraced the idea that government can and should lend a helping hand when it can.

This is the divide in American politics today, between those who think government is inherently oppressive and those who think government has an integral role to play in alleviating the various challenges a free society occasions. Increasingly, one side, the tea party side, refuses to negotiate or compromise. That unwillingness to compromise killed the farm bill for now. It may kill immigration reform. It has made a comprehensive budget deal a pipe dream. Call it intransigence. Call it standing by one's principles. But don't call it governance.

[Michael Sean Winters writes about religion and politics on his Distinctly Catholic blog.]