In this April 12, 2020 file photo, Pastor W.R. Starr II preaches during a drive-in Easter Sunday service while churchgoers listen from their cars in the parking lot at Faith City Christian Center in Kansas City, Kan. As the nation’s houses of worship weigh how and when to resume in-person gatherings while coronavirus stay-at-home orders ease in some areas, a new poll conducted April 30 - May 4, 2020 points to a partisan divide over whether restricting those services violates religious freedom. (AP/Charlie Riedel)

As the nation's houses of worship weigh how and when to resume in-person gatherings while coronavirus stay-at-home orders ease in some areas, a new poll points to a partisan divide over whether restricting those services violates religious freedom.

Questions about whether states and localities could restrict religious gatherings to protect public health during the pandemic while permitting other secular activities have swirled for weeks and resulted in more than a dozen legal challenges that touch on freedom to worship.

President Donald Trump's administration has sided with two churches contesting their areas' pandemic-related limits on in-person and drive-in services — a stance that appeals to his conservative base, according to the new poll by The University of Chicago Divinity School and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

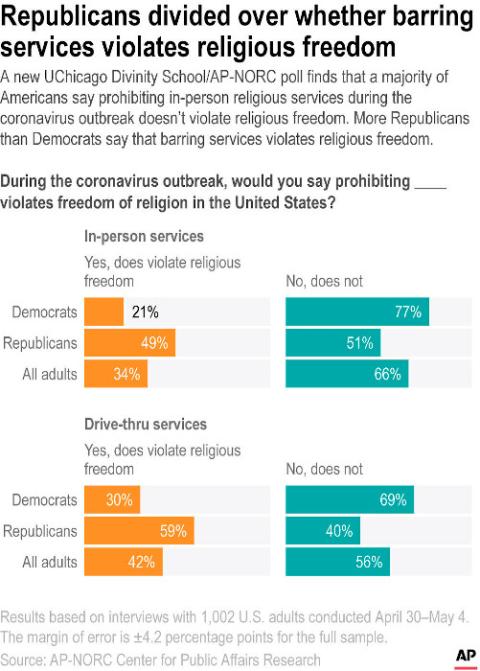

The poll found Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say prohibiting in-person services during the coronavirus outbreak violates religious freedom, 49% to 21%.

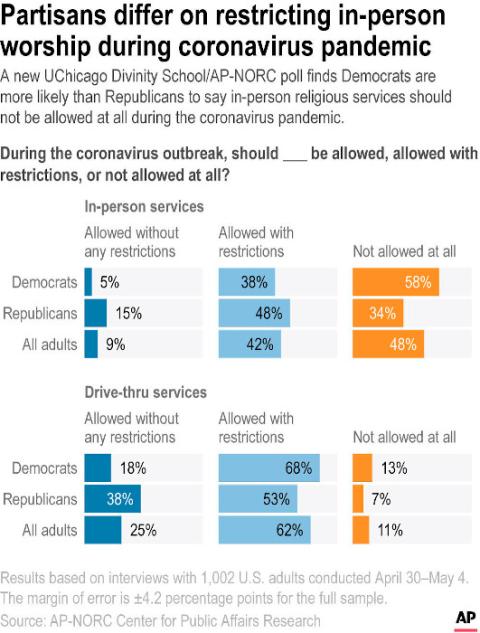

A majority of Democrats, 58%, say they think in-person religious services should not be allowed at all during the pandemic, compared with 34% of Republicans who say the same. Among Republicans, most of the remainder — 48% — think they should be allowed with restrictions, while 15% think they should be allowed without restrictions. Just 5% of Democrats favor unrestricted in-person worship, and 38% think it should be permitted with restrictions.

Caught between the poles of the debate are Americans like Stanley Maslowski, 83, a retired Catholic priest in St. Paul, Minn., and an independent who voted for Trump in 2016 but is undecided this year. Maslowski was of two minds about a court challenge by Kentucky churches that successfully exempted in-person religious services from the temporary gathering ban issued by that state's Democratic governor.

"On the one hand, I think it restricts religious freedom," Maslowski said of the Kentucky ban. "On the other hand, I'm not sure if some of that restriction is warranted because of the severity of the contagious virus. It's a whole new situation."

This poll shows Republicans are divided over whether barring services violates religious freedom

The unprecedented circumstance of a highly contagious virus whose spread was traced back, in some regions, to religious gatherings prompted most leaders across faiths to suspend in-person worship during the early weeks of the pandemic. But it wasn't long before worship restrictions prompted legal skirmishes from Kansas to California, with several high-profile cases championed by conservative legal nonprofits that have allied with the Trump administration's past elevation of religious liberty.

One of those conservative nonprofits, the First Liberty Institute, spearheaded a May 12 letter asking federal lawmakers to extend liability protections from coronavirus-related negligence lawsuits to religious organizations in their next coronavirus relief legislation.

Shielding houses of worship from potential legal liability would "reassure ministries that voluntarily closed that they can reopen in order to resume serving their communities," the First Liberty-led letter states.

Among the hundreds of faith leaders signing the letter were several conservative evangelical Christian supporters of Trump, including Family Research Council President Tony Perkins, and Rabbi Pesach Lerner, the president of the Coalition for Jewish Values.

John Inazu, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis who studies the First Amendment, said the letter's warning of legal peril for religious organizations that reopen their doors amid the virus appeared inflated. But he predicted further legal back-and-forth over whether eased-up gathering limits treat religious gatherings neutrally.

"I would think the greater litigation risk is not from private citizens suing churches but from churches suing municipalities whose reopening policies potentially disadvantage churches relative to businesses and other social institutions," Inazu said by email. "Some of those suits will have merit, and some won't."

Drive-through or drive-in services have grown in popularity during the virus as ways for houses of worship to continue welcoming the faithful while attempting to keep them at a reasonable social distance. Local limits on those services prompted high-profile legal challenges, including one of the two where the Justice Department weighed in on behalf of churches. The new poll also points to a partisan split on that issue.

Fifty-nine percent of Republicans say prohibitions on drive-in services while the outbreak is ongoing are a violation of religious freedom, compared with 30% of Democrats.

A new UChicago Divinity School/AP-NORC poll finds Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say in-person religious services should not be allowed at all during the coronavirus pandemic.

Republicans are also more likely than Democrats to say that drive-through religious services should be allowed without restriction, 38% to 18%.

Most Republicans and Democrats think drive-in services should be restricted, with few thinking they shouldn't be allowed at all.

Daniel Bennett, an associate political science professor at John Brown University, pointed to high support for Trump among white evangelicals — whom the poll showed are also more likely than others to say in-person worship should be allowed during the virus — as a possible driver of Democratic sentiment in the opposite direction.

Religious freedom can grow "more partisan when you have these white evangelicals who are such a key part of the Trump administration's voting bloc," said Bennett, who wrote a book on conservative Christian legal organizations. "It's a gut reaction to say, 'oh, you're for this — I have to be against this'."

Bennett pointed to a bigger question that predated, and promises to outlast, the virus: "How do we communicate these issues in terms of religious freedom while not alienating people for partisan reasons?"

(Swanson reported from Washington.)

(The AP-NORC poll of 1,002 adults was conducted April 30-May 4 using a sample drawn from NORC's probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 4.2 percentage points.)

Advertisement