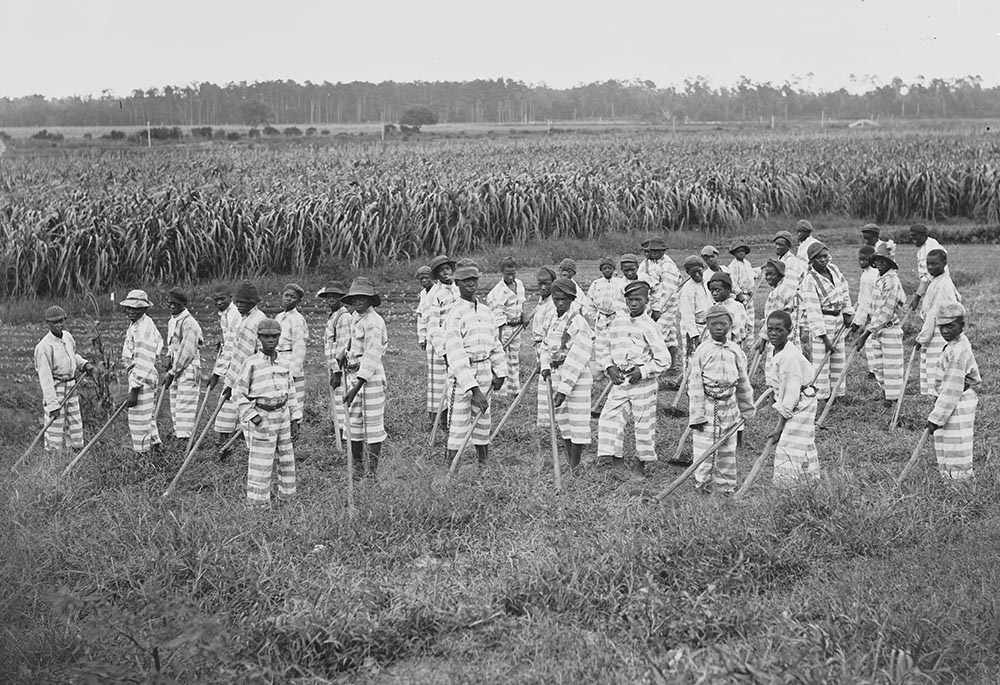

Juvenile convicts at work in fields, circa 1903 (Library of Congress/Detroit Publishing Company Collection)

Editor's note: A year ago, after the murder of George Floyd, the U.S. exploded with protests bringing attention to the scourge of police violence against African Americans. Initial calls to "defund the police" have since been nuanced to call for substantive reform that includes reappropriation of funds for other social services. But policing is just part of a massive justice system that includes courts, jails and prisons. In this four-day series, "Justice Reimagined," two NCR writers look at the prison abolition and reform movements, as well as what might work better: restorative justice. The three stories on prison abolition/reform are by Bertelsen fellow Madeleine Davison; former NCR executive editor Tom Roberts reported the two pieces on restorative justice.

Darrell Jones spent 32 years in prison in Massachusetts for a murder conviction that was later overturned. While he was in prison, his grandmother, his brother and his son all died.

"I couldn't go to their funerals," he said. "I couldn't say goodbye at all."

Jones, who is Black, said the case against him was based on racism and decided by an all-white jury. He'd never even seen the person he was accused of killing, he said.

In prison, Jones said, he was forced to work for less than $5 per week under the eye of mostly white male guards.

"I was a slave," he said.

Jones said he was caught up in a racist system of mass incarceration — one that swallows up hundreds of thousands of people every year in the United States, disproportionately Black men, according to the Sentencing Project.

Many people fighting for Black liberation and against white supremacy view the prison system as both a symptom and a driver of racism in the U.S., activists and scholars told NCR.

"Policing, surveillance [and] imprisonment have with startling uniformity been used to harm Black, brown and Indigenous people," said Dwayne David Paul, a Catholic educator and writer who works for the Collaborative Center for Justice but spoke to NCR in his capacity as a private individual.

Advertisement

Advocacy work to change or abolish the U.S. prison system is as old as the modern prison system itself, and has long been led by Black activists and scholars as well as incarcerated people themselves.

But especially in the year since white police officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd, a Black man, in May 2020, leaders of activist groups told NCR they've seen surging interest as people nationwide reexamine the roles of prisons and policing.

When it was first founded in 2019, Abolition Apostles, a Christian prison abolitionist group, was local to New Orleans and had no internet presence, said its co-founder, David Brazil. About two years later, it has more than 1,400 members across the country.

"There are moments of collective activation when people get politicized around these issues, and that happened last year," Brazil said.

In the U.S., activists are taking aim at perhaps the largest system of punishment on the planet: the country's prison system.

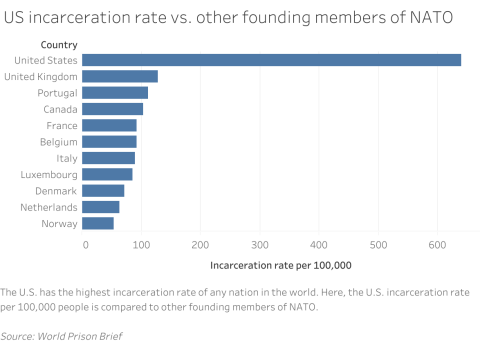

The United States has the highest per capita incarceration rate of any country in the world, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

Roughly 2.3 million people are currently behind bars nationwide, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, with another 4.4 million under some other form of correctional control, including parole, electronic monitoring and probation.

This system disproportionately affects Black, Latino and Indigenous people. Black people are incarcerated in state prisons at about 5.1 times the rate of white people, according to the Sentencing Project. In some states, one in 10 Black men is incarcerated at any given time.

Mass incarceration in America grew throughout the second half of the 20th century because of several factors, including racist tactics to control Black people and other people of color, a desire to warehouse unemployed populations, and "tough on crime" political rhetoric that intensified policing and sentencing laws, said Vincent Lloyd, director of Africana Studies at Villanova University and co-author with Joshua Dubler of Break Every Yoke: Religion, Justice and the Abolition of Prisons.

Many activists look at incarceration less as a form of justice and more as a legal, racial and economic system they call the "prison-industrial complex."

In her 2003 book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, activist and scholar Angela Davis defined the prison-industrial complex as "an array of relationships linking corporations, government, correctional communities, and media," where punishment is related more to economic and political conditions than to rates of crime or violence.

Davis noted that throughout the 1990s, as the violent crime rate was declining, the incarcerated population exploded. Since 1970, the total state and federal prison population has increased by roughly 700%, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Women's rate of incarceration has gone up even faster than men's in recent decades, said Syrita Steib, executive director of Operation Restoration, which serves currently and formerly incarcerated women.*

In her book, Davis argued that the prison boom of the 1970s through the early 2000s was partly a mechanism to control the freedom and harness the labor of Black and Latino people, replacing the chain gang system instituted during Jim Crow and descending from the control white people exerted over Black people during slavery.

"In the slaveholding South ... there really is a very disturbing straight line, from slavery to convict leasing to the chain gang to a lot of those prisons," said Kathleen Grimes, an associate professor of Christian ethics at Villanova who has written about the connections between slavery, Jim Crow and incarceration.

The incarceration boom birthed a for-profit sector that feeds off prison construction, weapons manufacturing for police departments, and fees and contracts for providing basic necessities such as food, clothing and communication technology to people behind bars, Davis wrote.

Rather than solving social problems such as violence, poverty, lack of health care and housing instability, prison inflicts more violence on the people it warehouses, she wrote.

"Prisons do not disappear social problems, they disappear human beings," Davis wrote.

On top of these factors, religion — especially Christianity — played a major role in building the prison-industrial complex, Lloyd told NCR.

The earliest examples of modern prisons in the United States — established in Philadelphia and in Auburn, New York, in the late 1700s and early 1800s — were founded on Christian principles, according to the Journal of Ecumenical Studies.

Early Philadelphia prisons — such as the Eastern State Penitentiary — were modeled on Quaker ideals, emphasizing solitary confinement and isolation, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Prisoners at Eastern State were given Bibles and expected to spend their time repenting of their sins in isolation from others, the Journal of Ecumenical Studies reported.

The ruins of a cellblock in Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary, which today is a historic site. The prison operated from 1829 to 1971. (Wikimedia Commons/Dudva)

Meanwhile, the Auburn Prison was constructed in 1816 on Puritan principles, according to the journal. The guiding principle was that people who committed crimes were inherently sinful. The prison was meant to rehabilitate (rather than reform) prisoners through hard forced labor, isolation and strict codes of conduct, the journal reported.

Changes in dominant Christian beliefs during the mid-20th century also played a role in the growth of mass incarceration, Lloyd said.

During the 1960s and 1970s, justice was reimagined in very legalistic terms among Christians in the U.S., he said.

"[It was] a shift away from theological language of justice ... and a reduction of justice to meaning getting even or simply following the law correctly," Lloyd said.

Today, Black and Latino people are overrepresented in the prison system due to systemic racism at every level of the criminal legal system, from policing to prosecution to sentencing, according to a report to the U.N. filed by the Sentencing Project in 2018.

For instance, although Black and white Americans use drugs at similar rates, Black people are roughly 2.7 times more likely than white people to be incarcerated for drug offenses, according to the Hamilton Project.

Young activists carry a banner for children of incarcerated parents during the March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C., on March 24, 2018. (Wikimedia Commons/Ziggyfan23)

Removing people from their homes and communities to send them to prison harms both those who are incarcerated and those who rely on them — especially children, said the Rev. Nikia Smith Robert, author of "Penitence, Plantation and the Penitentiary: A Liberation Theology for Lockdown America" and founder of Abolitionist Sanctuary.

The Urban Institute reported that an estimated 2.7 million children have a parent who is currently incarcerated, and 5 million children (roughly 7% of all U.S. children) have seen a parent incarcerated at some point, which can cause intense, long-lasting trauma.

Kazembe Balagun, a Christian activist who has been involved in a wide variety of Black liberation and anti-capitalist campaigns over the past several decades, said prisons rip people, particularly Black people, from their communities and tear apart families.

He said the prison system contradicts the biblical mandate to be merciful and forgive.

"This prison situation has made it to where we're not completely whole," he said. "And this question around abolition, and around faith, is really centered around — how do we make things whole? And that's why Jesus came, and that's why the church exists."

*This story was updated to clarify the description of the organization Operation Restoration.