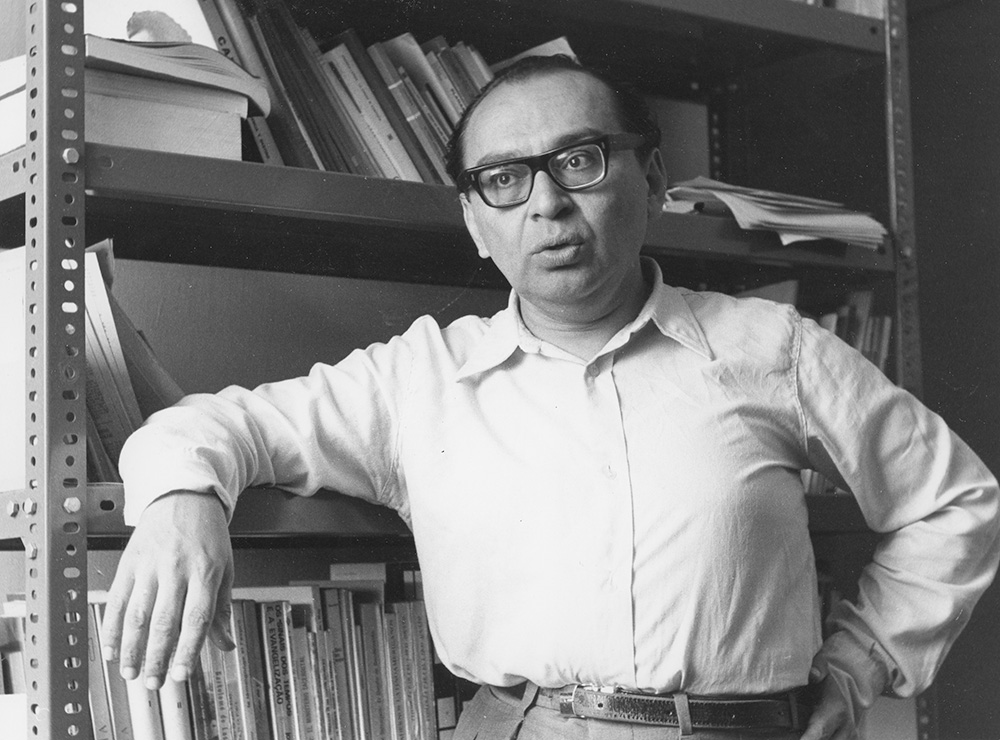

Dominican Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez in February 1974 (NCR photo/Agostino Bono)

The overwhelming response in the United States to Dominican Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez's death Oct. 22 at age 96 shows how the renowned Peruvian theologian's influence spread well beyond Latin America.

On Facebook alone, numerous clergy and laity posted tributes to Gutiérrez, whose 1971 book, A Theology of Liberation — considered one of the most influential theological texts of the 20th century — was a landmark in the development of liberation theology in Latin America and influenced similar theological movements, such as Black and feminist liberation theologies.

Sri Lankan Fr. Rohan Dominic, the representative of the Claretians at the United Nations, wrote in an Oct. 23 Facebook post that reading A Theology of Liberation during his formation years "was truly inspiring, creating an inner power to see and do things in a new way." Dominic said Gutiérrez's "prophetic vision profoundly shaped me, teaching me to look at realities through new eyes and equipping me with tools for social analysis."

"His message of God's preferential option for the poor and the call to transform unjust social structures has guided my missionary life ever since." Dominic said he had hoped to meet the "great maestro" during a visit to Lima last year but was not able to.

Describing himself as "deeply moved by the news of his passing," Dominic said that Gutiérrez's "legacy lives on in all who work for justice and liberation."

In an interview with NCR, the Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, the canon theologian at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., similarly said that Gutiérrez's work had tremendous reach. Even those theologians who did not make the poor central to their theology, she said, could not ignore the issue of economic poverty and injustices after Gutiérrez's contributions.

"He pointed out that poverty is not simply an economic problem. It's a moral problem" — an insight, she said, that is more relevant than ever.

She added: "You couldn't ignore Gustavo Gutiérrez," calling him "a paradigm shifter."

In a message to the staff of Orbis Books, editor and publisher Robert Ellsberg said that "apart from his historic contributions to the Church in Latin America and the emergence of liberation theology," Gutiérrez's work and the theology he inspired "fundamentally transformed the work of theology in North America and throughout the world."

Orbis, the publishing arm of the Maryknoll Society, published Gutiérrez's work in English.

Ellsberg added that Gutiérrez's theological project "is felt not only in the church's embrace of the 'preferential option for the poor,' but in the many schools of contextual, post-colonial, and liberation theologies that have emerged throughout the world."

Advertisement

The Orbis publisher noted that Gutiérrez's work was often "subject to vilification and withering criticism both by many church officials and even political figures." But, he said, Gutiérrez "was patient and diligent in defending his work against his critics." While the Peruvian theologian was long subjected to investigation by the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, "in the end he was never singled out for reproach."

A survey of Gutiérrez's writings makes clear why — they were always imbued with a deep sense of spirituality. We Drink From Our Own Wells: The Spiritual Journey of a People, published in Spanish in 1983 and then published in English a year later by Orbis ends this way:

Spirituality is a community enterprise. It is the passage of a people through the solitude and dangers of the desert, as it carves out its own way in the following of Jesus Christ. This spiritual experience is the well from which we must drink. From it we draw the promise of resurrection.

Gutiérrez even "lived to see some vindication," Ellsberg noted, with the conservative 2012-2017 prefect of the Vatican's doctrinal body, German Archbishop Gerhard Müller, becoming a "fan" and collaborator with Gutiérrez on the book On the Side of the Poor.

Moreover, to mark Gutiérrez's 90th birthday in 2018, Ellsberg noted that Pope Francis sent Gutiérrez celebratory greetings, thanking the Dominican priest "for what you have contributed to the Church and humanity through your theological service and your preferential love for the poor and the discarded of society."

In an introduction to a 50th anniversary edition of A Theology of Liberation, Gutiérrez acknowledged the various criticisms made of liberation theology. But he also took pride in the theology's impact, noting that it had "been welcomed with sympathy and hope by many and has contributed to the vitality of numerous undertakings in the service of Christian witness."

Dominican Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez, left, with Robert Ellsberg, editor and publisher of Orbis Books, in an undated photo (Courtesy of Robert Ellsberg)

Gutiérrez said debate about liberation theology within the Catholic Church at times caused "some painful moments at the personal level, usually for reasons that eventually pass away."

But, Gutiérrez said, he welcomed the debate as an "enriching spiritual experience," saying it proved to be "an opportunity to renew in depth our fidelity to the church in which all of us as a community believe and hope in the Lord, as well as to reassert our solidarity with the poor, those privileged members of the reign of God."

It was that solidarity which the University of Notre Dame celebrated in an Oct. 23 online memorial tribute. Gutiérrez taught at Notre Dame from 2001 to 2018 and at the time of his death was a professor emeritus of theology.

"Father Gustavo was a beloved member of the Notre Dame community, and we join with his family and fellow Dominicans in giving thanks to God for his extraordinary life," said Fr. Robert Dowd, a Holy Cross father and Notre Dame's president.

"His invaluable contributions as a scholar and theologian and his commitment as a priest to living out the Gospel call are an inspiration to us all," Dowd said.

In the Notre Dame memorial tribute, Holy Cross Fr. Daniel Groody, a professor of theology and global affairs and vice president and associate provost for undergraduate education, said of Gutiérrez: "The heart of A Theology of Liberation is God's love, God's life and God's creation. What was most important for Gustavo was not liberation theology, but the liberation of people. He combined a profound sense of the unmerited gift of God's love with the urgency of solidarity with those society considers the least important."

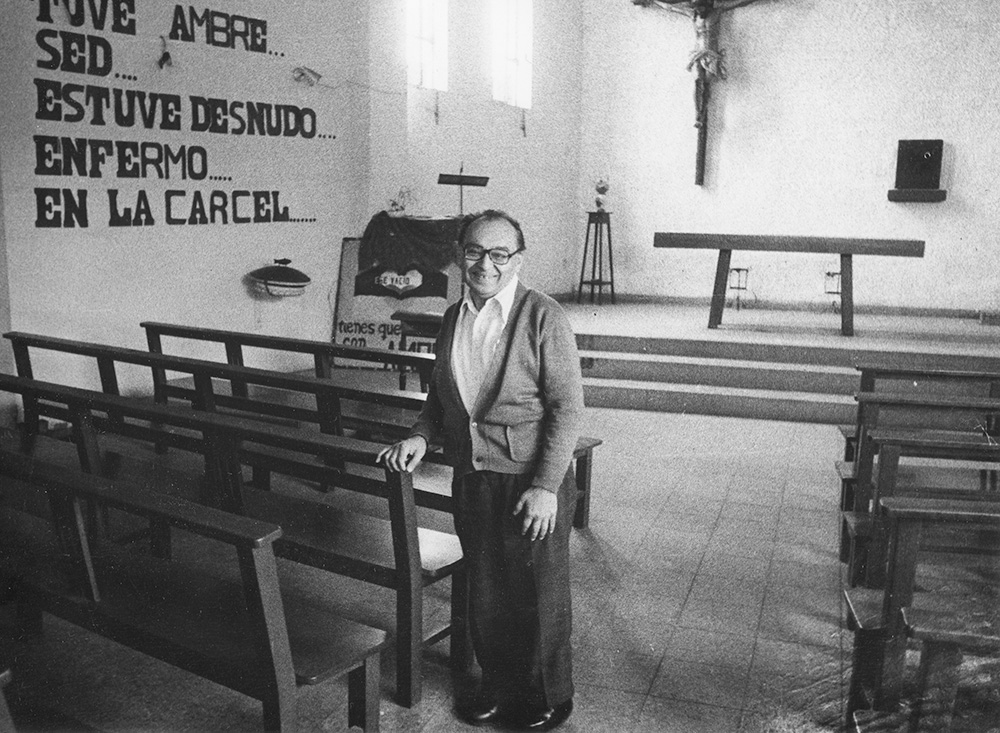

Dominican Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez in 1983 (NCR photo/Mark Day)

Another American institution, Union Theological Seminary in New York City, similarly praised the Peruvian theologian, who was a visiting professor there during the 1976-77 academic year.

In a statement, the Rev. Serene Jones, Union's president, said that Gutiérrez's "passing represents a tremendous loss for our community and the broader universe. Dr. Gutierrez's incredible legacy lives on at Union and beyond through the many lives he continues to touch through his pioneering vision for the empowerment of the world's most marginalized and oppressed communities."

Jones noted that liberation theology came "to contextualize the experiences of the poor, downtrodden, and oppressed." She said that one of Union's most famous scholars, the late James Cone, a leading figure in the development of Black liberation theology, acknowledged that that theology was "a continuation of the conversations Gutiérrez began."

Brown Douglas, who was a doctoral student of Cone's at Union, said that in those conversations, Gutiérrez's work was sometimes critiqued by Black and feminist theologians for its limitations in discussing race and gender issues. But, she added, Gutiérrez acknowledged those limitations and should be praised for developing the paradigm that made such critiques possible.

'Gutiérrez prophetically called us to see how capitalism is lethal to people around the world and carrying a preferential option for the poor is where we will find God and God's people.'

—The Rev. Sam Cruz

"I don't think any less of him for what he didn't say," Brown Douglas said. "It's what he did say that matters. He gave us the paradigm to critique and do theology in a new way."

She added: "It's our task to do the theology and push the boundaries that he started expanding."

In an interview, David Lantigua, an associate professor of theology at Notre Dame and the co-director of Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism, said that one of the "real and lasting contributions of Gutiérrez's work is to really think about that the option for the poor and the perspective of the poor in history. It has universal, global implications."

He said that the work of Gutiérrez and other liberation theologians in the early 1970s were early critiques of an emerging global neoliberal capitalism — critiques that have since been embraced by the Vatican.

In the statement issued by Union Seminary, the Rev. Sam Cruz, a professor of religion and society, said, "Gutiérrez prophetically called us to see how capitalism is lethal to people around the world and carrying a preferential option for the poor is where we will find God and God's people. With his passing during the times we are currently in, I am encouraged to hold his words even more true and continue his prophetic legacy."

Lantigua, who studied with Gutiérrez as a doctoral student at Notre Dame, said that while the critique of capitalism was a cornerstone of Gutiérrez's thought, the depiction of Gutiérrez's work as politically driven "was not an accurate portrayal of his theology."

Rather, he said, it was grounded in the idea of a "concrete encounter of the God of history through the poor, and being evangelized by the poor. This was essential for Gustavo."

Ellsberg said that Gutiérrez was easily Orbis' best-selling author over the last 50 years. A Theology of Liberation, at 92,757 copies over three editions, remains his best-selling book. That would be followed, Ellsberg said, by We Drink From Our Own Wells, selling 49,764 copies, and On Job, at 44,685.

While Ellsberg recounted those numbers with pride, he said, "Those who knew Gustavo knew he was one of the kindest, humblest, most faithful disciples of Jesus that we have ever known. A brave, brilliant and holy man."

Lantigua agreed, recalling his mentor as "incredibly humble. He was incredibly approachable. He had that way about him. He had a peace and joy about him that stood out."

To Gutiérrez, "theology was a way of living" and best done in the company of friends, Lantigua said. "He was genuine, simple and [displayed] an endearing kind of friendship."

"His humanity," Brown Douglas said, "always came through in his theology."