War destruction as seen in Izium, Ukraine, on Dec. 8. (Marcin Mazur)

Three months ago, Ukraine's eastern region of Kharkiv was liberated from Russian forces after a six-month reign of terror that decimated 80% of its high-rise residential buildings, destroyed most of its schoolrooms and municipal buildings and left more than 400 mass graves in its wake. Now, new construction is underway.

All of the windows in the local hospital shattered by Russian shelling have now been replaced and on Dec. 8 — the feast of the Immaculate Conception — the head of surgery is expecting new patients. With a slight smile, he notes that the new arrivals will not be from war casualties, but injuries resulting from the ice and snow.

Just up the road, at what was once Izium's town hall, another construction project, of sorts, is in progress: A mural is being painted on its heavily bombarded façade representing popular cartoon characters dating back to the 1960s, known as Cossacks. These heroic figures are recognized as thoroughly Ukrainian and after nearly 10 months of savage war, are being freshly painted to represent the country's resilient identity.

A "Cossack" cartoon mural is painted on the former city hall in Izium, Ukraine, on Dec. 8. (Marcin Mazur)

From Izium, it's about an eight-hour drive west to the capital city of Kyiv, where another art display opened May 8, just over two months after the Feb. 24 Russian invasion began.

Here, at a World War II museum, a special exhibition's title uses decidedly religious language to encapsulate the toll of the war: "Ukraine Crucifixion."

The exhibition wasted no time in quickly memorializing the effects of the war, often with religious artifacts. A painting of Jesus being taken off the cross that was hit by shrapnel hangs in the center of one room and display cases contain damaged icons and crucifixes placed atop Russian bullets.

"Religious symbols are widely understood by Ukrainian people," said Dmytro Hainetdinov, a museum official. "The symbol of crucifixion is not only the symbol of reprisal, but also the symbol of resurrection."

"This is important to underline our belief in the victory and resurrection of Ukraine," he added.

Damaged icons and crucifixes sit atop Russian bullets at the "Ukraine Crucifixion" exhibit in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Dec. 8. (NCR photo/Christopher White)

And be it in neighboring Poland — where 8 million Ukrainian refugees and displaced persons have crossed into since the war's outbreak — or among those who remain in Ukraine, there is widely shared determination, often spoken of with religious conviction, that however long is necessary, the country is willing to continue battling Russia to defend its territorial integrity.

Such a position has caused some tension with the Vatican, which, while having acknowledged Russia as the aggressor in the war, is eager to accelerate peace negotiations.

The respective Vatican embassies in Poland and Ukraine organized a Dec. 4-10 trip to both countries for journalists from five news outlets, including NCR. During the trip, government officials, nongovernmental organization workers, religious leaders and residents acknowledged that this war that began just ahead of Easter was going to give way to a Christmas like no other.

Advertisement

"We are living a moment of transformation," said Kyiv-Zhytomyr Archbishop Vitaliy Kryvytskyi, who told the journalists gathered around his dining room table in the heart of the capital that the war had brought the country together as one family.

Kryvytskyi spoke for many of the country's leaders and citizens alike when he acknowledged a desire for peace, but indicated it seemed to be a distant horizon.

"Every missile that falls lengthens the peace process," he said. "And peace will not come the next morning. It is a process."

The cost of war

From his second-floor office on Dec. 7, Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights (or Ombudsman) Dmytro Lubinets offered a summation of a November governmental report titled "The War Against Human Rights": 10,189 wounded civilians since the war began; 6,595 civilians killed; 12,340 children forcibly taken to Russia; 440 children killed; 140,000 houses destroyed; 205 religious buildings destroyed; and 14.03 million people homeless.

The site of more than 400 mass graves in Izium, Ukraine, is seen on Dec. 8. (Marcin Mazur)

Downstairs, in his building's lobby in central Kyiv, staff members scurry about decorating for Christmas while English-language holiday music fills its corridors. It's just one scene representative of so many in a country trying to adapt to the new realities brought about by war.

In the capital city, thousands still commute to work using the metro, and restaurants and cafes remain open, merely adapting their menu based on what food can be procured and whether or not they have the necessary electricity to prepare it. In places such as Izium, residents are still combing through the remains of their former homes and workplaces, trying to salvage what they can, while assuring themselves, and anyone who might visit, that they will rebuild.

The numbers, as outlined by the ombudsman's report, are necessary data points, but each one tells its own tale of struggle and loss.

Former residential buildings in Izium, Ukraine, on Dec. 8. The city was hostage to Russian forces from March to September 2022. (Marcin Mazur)

The day before the report was read aloud, on Dec. 6, in the southeast border town of Przemyśl, Poland, our delegation visited a mother and child center where new arrivals are provided food, shelter and support provided by CARE International.

At the Greek Catholic Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, chancery offices have been converted into lodging, with ongoing construction signaling that the task of welcoming new refugees is unlikely to come to an end anytime soon.

There are so many stories under one roof: A room containing 20 bunk beds has been inadvertently transformed into a playground by toddlers climbing about and running around their makeshift home, while an elderly woman reads a book, as she reclines against her luggage. When asked where she arrived from, all she can utter before beginning to cry is "Bucha" — the city where a bloody massacre in March left behind mass graves and accusations of Russian genocide against Ukraine.

A refugee from Bucha, Ukraine, at the Greek Catholic Cathedral in Przemyśl, Poland, on Dec. 6 (Marcin Mazur)

In another room is Nadia (who asked to withhold her last name), who at age 74 just arrived in Poland, following the advice of Kyiv's mayor, who advised the city's elderly residents to leave for the winter, fearful that there will be long periods without heat or electricity.

"When the first bomb went off, I was at my son's, out of town," she said, recalling the start of the war. "I came back weeks later but didn't recognize my home."

"I decided to stay anyway, but now they told me it was better to leave," she continued. "But I have no plans for my life."

In the city of Rzeszów, Poland, on Dec. 5, about 20 Ukrainians arrived at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reception center to take Polish language classes. Most are shy and hesitant to share their stories, but they call out the names of their respective home cities: Mariupol, Donetsk, Odessa.

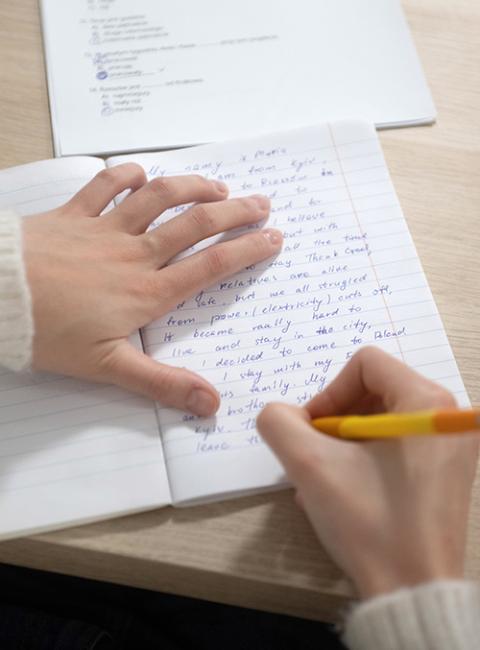

One student — Maria, who provided only her first name, age 20 — asked if she could write out a short testimonial.

Maria, a refugee from Kyiv, writes about her escape from Ukraine at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reception center in Rzeszów, Poland, Dec. 5. (Marcin Mazur)

"I am originally from Kyiv," she wrote in English. "I came here to Rzeszów in November. I wanted to stay in my motherland for as long as the war would last, because I believe it is my duty. But with these missile attacks all the time, it was difficult to stay."

She continued, noting that half of her family is in Poland and the other half remains in Ukraine: "I want to return as soon as the situation improves. But we are all grateful for the hospitality of the Polish people. For now the most difficult thing is to find a good job here and the prices for apartments."

The outpouring of support from Poland since the start of the war has been unrivaled in Europe. Since February, the country, which has a complicated history with Ukraine, has spent more than an estimated $8 billion euros in response to the largest refugee crisis in Europe since World War II.

According to Władysław Ortyl, president of the Podkarpackie region, nearly 4 million Ukrainian refugees have passed through his district since February.

The government's support, which has included funds for children starting school and providing medical care, is based on the principle of "giving refugees the same rights as Polish citizens," which has been complemented by Catholic relief agencies, such as Caritas, the Order of Malta and a host of religious communities.

Visit to the Medevac Hub for Ukrainian refugees in Rzeszów, Poland, on Dec. 5 (Marcin Mazur)

While Russia has targeted critical Ukrainian infrastructure in recent months, in an effort to flood Poland and the rest of Europe and overwhelm the continent with even more refugees in hopes of stirring up internal dissent there, Ortyl says he is aware of what may soon be coming and is unfazed.

"Before us is the possibility of a second wave because of destroyed infrastructure, cold, lack of water and services," he said. "People want to get out. We are ready."

Welcoming the 'Prince of Peace'

On Feb. 25, the morning after war began, Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk, the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, released a short video pleading for solidarity and prayers for Ukraine.

Shevchuk and around 100 others bunkered below his cathedral in Kyiv and the following day released another video, providing an update and spiritual support. Soon these daily videos became a lifeline to the outside world.

As the war lingered on with no end in sight, he considered reducing the frequency of his messages or stopping altogether, until one day he visited the besieged city of Žytomyr.

A statue of Vladimir the Great overlooks Dnipro River in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Dec. 7. (Marcin Mazur)

"At a parish, a little old lady approached me to say, 'We live in constant terror, we are afraid, it is good that you talk to us,' " he recounted to the journalists who visited him at his cathedral Dec. 9.

" 'But ma'am, I don't know what to tell you anymore!' " the archbishop replied.

" 'No matter what you say, it matters that you talk to us,' " she countered.

"Then I realized that even if I don't know what to say anymore, it is important for people to hear the voice of their church accompanying them," said Shevchuk.

As the war rages into its 10th month, the country's religious leaders — in a nation where, historically, church and state already have a paper-thin separation — have been on the front lines.

The Ukraine Council of Churches, composed of 16 different representatives, including Christians, Jews and Muslims, unites 95% of religious institutions in Ukraine.

"War has given us a new opportunity to collaborate," said Kyiv's Archbishop Kryvytskyi.

During a meeting with the council, the religious representatives said that while the Gospel's call to be peacemakers and their desire for peace is strongly present in their work, Kryvytskyi also said, "Our obligation is testifying to the truth."

While, historically, many of the country's Protestant traditions have been rooted in the pacifist tradition, members of the council noted that those tendencies have been challenged ever since Russia illegally annexed Crimea in 2014. Even those who refuse to take up arms, they note, have not shied away from helping war efforts in other capacities.

And at this point, that truth-telling of the council, as they see it, means speaking bluntly that, in the words of Shevchuk, Russia must "stop military actions, stop killing us."

"This will be the first step to genuine and lasting peace," he said.

With the onset of winter and just a few weeks before Christmas, there is uncertainty as to what lies ahead.

Former city hall offices in Izium, Ukraine, on Dec. 8 (Marcin Mazur)

High-rise residential buildings, warned Jan Sobiło, auxiliary bishop of Kharkiv- Zaporizhzhia, "will become refrigerators" if the country keeps facing strikes on its power grid.

But how can and how should a country and the church in these circumstances face Christmas?

On Dec. 14, Pope Francis launched a special appeal, asking all people of goodwill to spend less on gifts and other celebrations, and instead donate money to support Ukrainians.

"Brothers and sisters," the pope said, "I tell you, they are suffering so very, very much."

Sobiło said that in late November, he visited Rome to meet with Francis and saw Christmas preparations underway at the Vatican.

Destruction in Izium, Ukraine, on Dec. 8 (Marcin Mazur)

"I wonder if we in Zaporizhzhia will also be able to have a tree in the square?" he recalled thinking.

He concluded that was unlikely, but said it doesn't mean that both churches and individual homes shouldn't prepare for the arrival of Jesus.

"Christ was born in a dark, cold cave with the light of a candle, and we too will welcome the newborn Jesus in the warmth of our hearts, despite the cold around," he said.

"Everyone now asks: Will there be Christmas joy, will it be permissible to sing or should we shut up and cry?" said Shevchuk. "I say yes and yes, Christmas will be there. We have the right to celebrate Christmas joy ... because the Prince of Peace will be born."

As believers prepare to welcome the Prince of Peace, new polling suggests that some 85% of its citizens believe the fighting should continue until Ukraine regains all of its territories. This Christmas, crucified Ukraine — martyred Ukraine, as Francis has frequently referred to it — seems very far from resurrection, though its citizens are unshaken in their faith that it will one day arrive.