Pope Francis walks near a flag with the national colors of Ukraine during his general audience in the Paul VI hall at the Vatican March 16. (CNS/Vatican Media)

For four weeks, the Vatican has offered to serve as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine, and for four weeks, such overtures have been ignored by Russia.

As Russia's war against Ukraine rages on, Pope Francis has incrementally escalated his rhetoric against the invasion, condemning it as an "unacceptable armed aggression," while refusing to directly name President Vladimir Putin or Russia as the aggressors.

The diplomatic tightrope has been defended as consistent with longstanding Vatican neutrality, necessary for protecting Catholics in both Ukraine and Russia and as an effort to preserve any possible role the Holy See could play in brokering a peace deal.

Others, including those generally sympathetic to Francis, have criticized the approach as a failure to use the pope's far-reaching megaphone to directly condemn Putin and prevent further aggressions, too cautious in an effort to advance ecumenical relations with the Russian Orthodox Church. Critics have also expressed skepticism of the possibility of the Vatican actually being able to serve a role in negotiating a ceasefire.

The Vatican's diplomatic corps is the oldest in the world, with a reputation for notoriously discreet and calculated approaches to geopolitical engagement.

Advertisement

Francis now faces one of the greatest international challenges of his nearly decadelong papacy, and the tensions over the Vatican's approach to Ukraine and Russia reveal the complex web of intra-ecclesial politics and influence of the global cast of characters who craft and compose the Holy See's role in the world stage.

As religion meets realpolitik, at stake is the Catholic church's hopes for greater unity with other Christian confessions, a desire to protect the identity of local Catholic congregations and the tremendous challenge of overcoming long-held Russian suspicions of Roman Catholicism.

Vatican-Russian relations

To understand the current moment, according to Victor Gaetan, author of God's Diplomats: Pope Francis, Vatican Diplomacy, and America's Armageddon, one must return to the papacy of Pope Benedict XVI.

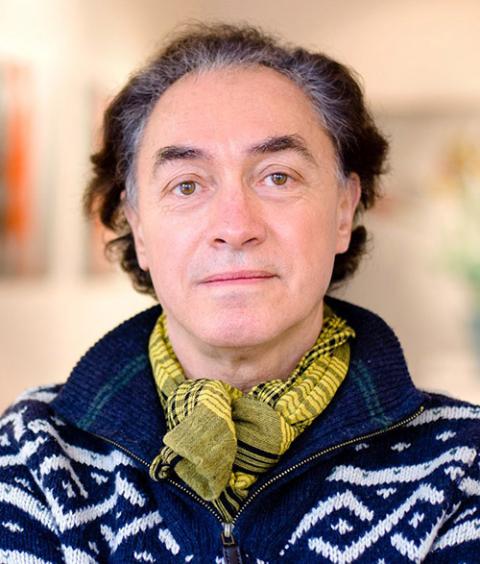

Victor Gaetan (CNS/Erin Scott)

Benedict, elected in 2005, and Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill, elected in 2009, are both respected theologians of their own traditions and both saw eye-to-eye on the need to fight against the rising tides of moral relativism in the West.

Soon thereafter, in 2010, the Vatican and Russia exchanged ambassadors with full diplomatic recognition, for the first time in nearly a century.

"This is the period when the relationship between the Holy See and Russia, and the Holy See and Kirill, began blossoming," Gaetan told NCR.

That relationship would help pave the way for an eventual in-person meeting in Cuba between Pope Francis and Kirill in 2016, the first-ever meeting of a Roman Catholic pontiff and the Russian Orthodox patriarch.

During this time from 2009 to 2012, Gaetan noted, a Lithuanian-born Vatican diplomat, then-Msgr. Visvaldas Kulbokas, was stationed at the Vatican embassy in Moscow, providing him a front-row seat to the complicated realities of Russia-Vatican relations.

From 2012 to 2020, Kulbokas worked at the Vatican's Secretariat of State, where he served as the translator for meetings between the pope and Putin, and, according to Gaetan, was part of the "small team" that prepared the highly sensitive meeting between Francis and Kirill in 2016, where he would again serve as translator.

Then-Msgr. Visvaldas Kulbokas, center, serves as translator as Pope Francis and Russian President Vladimir Putin exchange gifts during a private audience at the Vatican July 4, 2019. (CNS/Paul Haring)

In June 2021, Kulbokas was given a new assignment: to serve as the Vatican's ambassador in Ukraine — a country of about 44 million, with about 5 million Catholics.

According to Gaetan, the vibrant Catholic community, mostly in western Ukraine, had both a tense relationship with its Orthodox neighbors in the east, and was eager for closer relations with the West and the European Union, especially following Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014.

It fell to Kulbokas to navigate those divides.

A religious cold war?

Tamara Grdzelidze, who served as Georgia's Vatican ambassador from 2014 to 2018, told NCR that when she arrived in Rome to assume her duties, it was shortly after the Crimea annexation.

Drawing on her own experience of Russia's military attack on Georgia in 2008, she cautioned both her fellow ambassadors and Vatican officials to wake up to the threat of Russia. At one event, she recalls specifically speaking to Ukrainians and warning "what they did in 2008 in Georgia, it will be the same for you if the West fails to recognize it properly."

Ulla Gudmundson, Sweden's Vatican ambassador from 2008 to 2013, told NCR she recalled Baltic representatives to the Vatican being upset when the Holy See would refer to conflict between Ukrainians and Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine as a "civil war."

Ulla Gudmundson (ullagudmundson.se/Charlotta Smeds)

"This was falsifying reality to them," Gudmundson said.

In 2021, Italian Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin traveled to Vilnius, Lithuania, for the primary purpose of ordaining Kulbokas as archbishop. Ukraine is a country, Parolin said at the ordination Mass, that "experiences conflicts difficult to fully overcome."

Ukraine's eastern-rite Catholics are led by Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk, who has known Francis since Shevchuk was posted in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2009 as the head of the diaspora community of Ukrainian Greek Catholics.

Since his 2011 election as head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Shevchuk has not been shy about his concerns about Russia, repeatedly warning that Russia sought a return to an era of Soviet-style rule, which would have grave implications for the country and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

During this time, the Vatican, according to Gaetan, relied on Kulbokas to help further relations with the Orthodox in order to prevent a "religious cold war."

Yet George Demacopoulos, co-director of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center at Fordham University, told NCR he questioned the sincerity of the Russian Orthodox Church's interest in ecumenical relations.

"Kirill positioned the Russian Orthodox Church as the sole defender of traditional values around the world," he said. "What hope is there for ecumenical relations if with every passing word, you're suggesting that there is no value in the West and that anyone who believes in liberal democracy, protection of minority rights and pluralistic societies are by definition satanic?"

"That's not going to win you any ecumenical friends," he said.

Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk of Kyiv-Halych, head of the Eastern-rite Ukrainian Catholic Church, is pictured during a meeting with Ukrainian refugees in Lviv, Ukraine, March 10. He was joined in the visit by Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, the papal almoner. (CNS/Courtesy of Ukrainian Catholic Church)

Beyond Francis' desire for reconciliation between the two churches, Demacopoulos said that in his estimation, one potential reason that the Vatican and the Russian Orthodox Church, which is the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches, had found an alliance is over certain culture war fights, particularly when it comes to opposition to gay marriage and women's ordination.

"The Kremlin's alliance with Kirill has been critical in instrumentalizing selective Christian principles for political gain," he said. "I can imagine that one of the reasons the Vatican, up until Putin really showed his hand, really championed some of the rhetoric that he [Kirill] uses is precisely because they themselves are aligned with some of the traditional values."

Vatican neutrality

In Rome, the tensions, sometimes real and other times perceived, between the need for unity among religious believers and preserving strong identities among local churches have played out through two Vatican offices beyond the Vatican's Secretariat of State: the Congregation for Oriental Churches, headed by Argentine-born Cardinal Leonardo Sandri, and the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, led by Swiss-born Cardinal Kurt Koch.

"You could say they offer two different perspectives of the same lands," said Gaetan.

Cardinal Leonardo Sandri, prefect of the Congregation for Eastern Churches, prays for peace in Ukraine during a prayer service at the Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus in Rome March 2. (CNS/Ukrainian Catholic Excharate of Italy/Rostyslav Hadada)

Koch has prioritized relations with the Russian Orthodox and was closely involved in the pope's 2016 meeting with Kirill. Just before the outbreak of the war, Koch and others were preparing for a second meeting between Francis and Kirill that was expected to take place this summer, a possibility all but now officially crushed by the war and Kirill's continued defense of it. When Francis, on March 16, met via video conference with Kirill and rejected his framing of the Russian invasion on religious grounds, it was Koch who was by his side.

Sandri, who is known to have close relations with Francis given their shared homeland, convened a major Vatican summit of Eastern church leaders in Rome on the eve of the war in February. In an audience with Francis at the end of the conference, the pope acknowledged the "threatening winds" of conflict that confronted both the countries and the local churches.

Metropolitan-Archbishop Borys Gudziak of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia told NCR in February that during that meeting with the pope, he directly discussed the need for the Holy See to speak forcefully about the threats to Ukraine.

Since the invasion, both Shevchuk and Kulbokas have remained in Kyiv, with Shevchuk releasing daily video messages calling for an end to Russian aggression and Kulbokas celebrating daily Mass in the nunciature's kitchen to avoid the shelling. During his March 20 Sunday Angelus, Francis specifically praised Kulbokas for remaining in Kyiv and being present with those suffering from war.

Archbishop Visvaldas Kulbokas, apostolic nuncio to Ukraine, elevates the Eucharist in the kitchen at the apostolic nunciature in Kyiv, Ukraine, in this recent photo. During the war, Archbishop Kulbokas has been celebrating Mass in the kitchen because it's a well-protected area. (CNS/Courtesy of Archbishop Visvaldas Kulbokas)

While Kulbokas has been cautious and limited in his public statements, in a recent interview with the Catholic news site Crux, he defended the Holy See's approach in this current crisis.

"When we hear the Holy Father talking about war, there is no neutrality: He condemns it with the strongest wording, underscoring that every war is an invention of the devil, is a satanic work," Kulbokas said.

Former ambassador Gudmundson, however, told NCR that "when human rights, respect for human lives, etc. are being violated by one party, it becomes increasingly difficult not to name the aggressor," but she added, "I suppose it's not the end of the world if the pope does not mention Russia as the aggressor, if there is a tiny chance that he can somehow work on Kirill."

Tamar Grdzelidze (Wikimedia Commons/Centro Televisivo Vaticano)

Former ambassador Grdzelidze said that she, too, "appreciated the Vatican's approach of never mentioning particular parties," but added that this stance allows the party or parties at fault to manipulate the Vatican's position.

"Hidden negotiations don't work with Russia. The underlying policy of their diplomacy is lying," she cautioned. "The Vatican's diplomacy works with civilized countries, but not with Putin. They should talk with and to Russia directly and name things, but they don't."

The pope as peacemaker?

Both Francis and Parolin have held out hope that the Vatican's neutrality will allow it to ultimately save more lives and to be available to serve a role as peacemaker if possible. Ukrainian President Vladimir Zelensky has expressed openness to that idea in the past, but Russia has not indicated any interest.

Grdzelidze, who is also an Orthodox theologian and served for 13 years at the World Council of Churches in Geneva, said. "Kirill is 100% behind Putin's approach."

Fellow Orthodox theologian Demacopoulos concurred.

"The pope is genuinely trying to do the right thing and reach out to a church that he respects and to advocate for peace," he said, "while the institutional Russian Orthodox Church is simply taking advantage of him for their own opportunistic, Kremlin-narrative purposes."

Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, head of external relations for the Russian Orthodox Church, participate in a video meeting with Pope Francis and Swiss Cardinal Kurt Koch, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, March 16. (CNS/Courtesy of Russian Orthodox Church)

"My own take is to name the aggressor," he said. "If you really are going to be the advocate of the oppressed, then it could be constructive to name the oppressor."

But in a recent interview in the British Catholic journal The Tablet, the former Vatican nuncio to Ukraine, Archbishop Claudio Gugerotti, insisted, "President Putin listens to the pope."

In 1978, the Vatican intervened in a peace negotiation between Argentina and Chile in a conflict over the Beagle Channel, successfully staving off an armed conflict, in part because the Vatican held a unique ability to influence the two deeply Catholic South American countries.

Michael Kimmage, who served on the policy planning staff at the U.S. State Department from 2014 to 2016, where he was responsible for the Russia and Ukraine portfolio, said in his view it was "absolutely not possible" for the Vatican to broker a peace deal in the current war.

Michael Kimmage (Wilson Center)

There is an "old fashion narrative," Kimmage told NCR, that the Catholic Church is a "traditional enemy" of Russia. This is a "long-standing Russian frame," he said, that makes the geopolitics of the moment very difficult for the Holy See to navigate.

His assessment has been shared by a number of other leading regional experts who warn that Putin's grip on the Russian Orthodox church severely limits any role the Vatican can play.

Instead, Kimmage, who is the chair of the history department at the Catholic University of America, said that the Holy See's role should be "speaking to the conscience of other European leaders."

In recent weeks, the pope has sent two cardinal emissaries to Ukraine to express his closeness to those fleeing violence and has repeatedly spoken by phone with Ukraine's president and Catholic leaders. At the same time, both Zelensky and the mayor of Kyiv have appealed directly to Francis, asking him to visit the Ukrainian capital, saying his physical presence in the war-torn country may be one of its last opportunities for bringing about peace.

For Kimmage, the church's "moral stewardship" and vast network are needed in responding to the humanitarian crises, which, he said, "are legion and still to come" and to "help knit together Ukrainian society" after the war.

When that time will come — and what Francis and the Vatican will say or do in between then — remains to be seen.