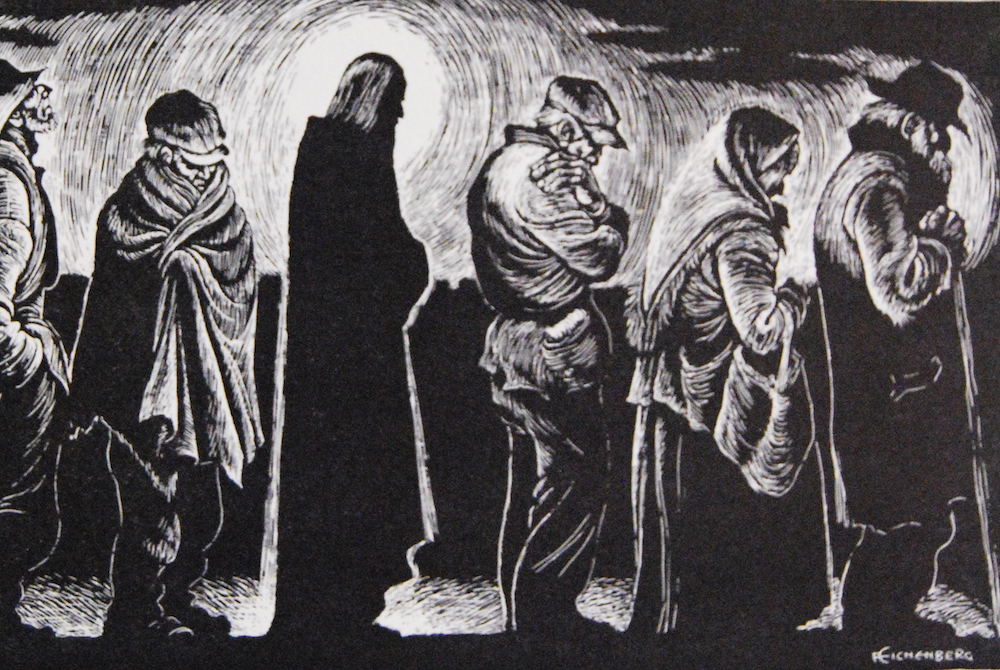

"Christ of the Breadlines" by Fritz Eichenberg, 1952, shared to the Catholic Worker (Flickr/Jim Forest)

Today's feast is celebrated under the leave-nothing-understated title of The Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe. Through history, Christians have produced a wide variety of images of Christ as King. There's Michelangelo's super muscular, Apollo-like Jesus who raises the blessed and dismisses the damned. Orthodox icons generally depict a savior more serious than welcoming, and many popular depictions present Jesus crowned and resplendent in royal/priestly robes.

Most of these images stand in stark contrast to today's Gospel. In today's parable, Jesus gives us the image of a shepherd segregating sheep and goats, an undemanding task generally left to children or the elderly. But in this case, it's Earth-shatteringly important, illustrating the eternal division created between those who revel in the company of God's beloved and those who have sought no place among them.

The characters who populate this last parable in the Gospel of Matthew might represent everyone with whom Jesus came in contact during his ministry. Ironically, none of the people represented by sheep and goats anticipated this kind of judgment. None had consciously recognized Christ in others, especially not in people who needed help.

Among the stunned "goats," we might find leaders who censured Jesus for healing on the Sabbath or for fraternizing with people of ill repute. There, too, we might find folks like the rich man who prided himself in obeying every law, but ultimately chose his own fortune rather than join Jesus' company. Among the surprised sheep, we might discover the woman who didn't let Jesus get away with withholding a miracle to a foreigner and the centurion who begged on behalf of his servant. Along with them, we'd find the disciples whose foibles were glaring, but who kept trying to be faithful and to serve as Jesus did — even to the point of being willing to invite a crowd of thousands to share their few loaves of bread.

We need to remember the key to this parable: neither the sheep people nor the goat people had guessed at the criteria that would determine their fate. If advised to prepare to face God's judgment, many of them might have reviewed how they had observed the "thou shalt not" commandments. Disciples might have reviewed whether they really had left everything to preach the Gospel. Some Christians of later times came to believe that their final test would measure how they had maintained doctrinal or liturgical orthodoxy or complied with the church's moral (read sexual) mandates. But none of that figured into Jesus' final exam.

Advertisement

In modern times, The Baltimore Catechism tells us quite clearly what the Son of Man seeks. In response to the question of why God created humanity, we answer that we were created to "know, love and serve God in this world." But as Hamlet would say, "Ay, there's the rub." How do we know God, much less love and serve God?

Today's parable tells us that the Son of Man, Jesus Christ, the King of the Universe, chose once and for all to be in solidarity and identify himself with the lowliest people. Maybe it's time to relegate the Sistine Chapel, awe-inspiring icons, and portraits of the royal redeemer to museums. If we want to respect Jesus' self-portrait, we would do better to contemplate Fritz Eichenberg's "The Christ of the Breadlines," a black and white etching of a slightly stooped, racially indistinct Christ, distinguishable from the destitute women and men with whom he waits by nothing more than how his presence radiates out to them. "The Christ of the Breadlines" illustrates Christ's choice to identify with the vulnerable. Whereas humanity tends to envision the divine as the utmost expression of magnificent "things that matter," Jesus tells us to seek God's self-revelation at the lowest end of the scales of power and prestige.

Jesus didn't tell this parable to scare us into charity. That motivation would leave us trapped in our egoism, even if we did lessen others' suffering. Jesus knew that genuine encounters with the poor enlarge the heart and the vision of the givers. Solidarity makes us all more human.

Christ invites us to know him in relationship with his beloved poor. When we fall in love with Christ in the poor and with the poor in him, we will inevitably want to serve him in and with them. According the Beatitudes, that will make us happy in this world and the next.

This feast encapsulates the Gospel irony of firsts and lasts, of losing life and finding it. One way to sum it up combines The Baltimore Catechism with Pope Francis and says that those who decide to know, love and serve Christ, the King of the Universe, will end up smelling like his sheep. Happily ever after.

[St. Joseph Sr. Mary M. McGlone serves on the congregational leadership team of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet.]