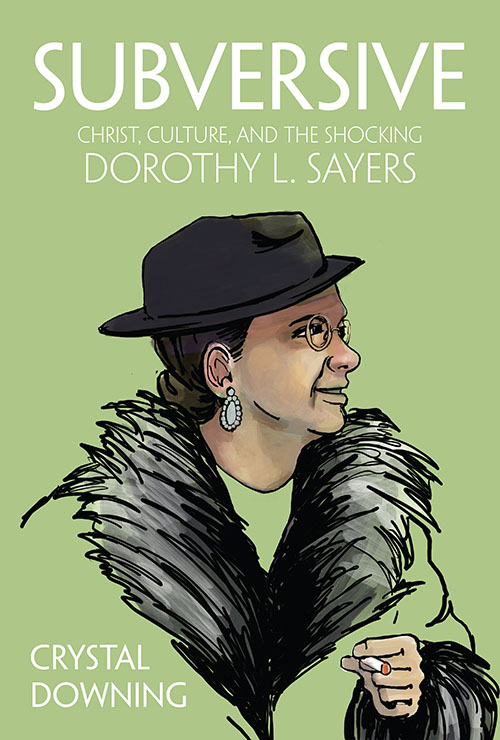

Dorothy L. Sayers signs a visitors' book Feb. 6, 1942, at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church in London, where she addressed the congregation at a lunchtime service. (AP Photo)

You can say almost anything about Jesus Christ, according to Dorothy L. Sayers, but you cannot say that he is dull. Nor can you find the murder of God tedious. But, she says, the average Christian does just that.

In Subversive: Christ, Culture, and the Shocking Dorothy L. Sayers, Crystal Downing skillfully traces the ramifications of that premise through Sayers' books, plays, poems, essays, letters and the events in her personal life.

Primarily known for her Lord Peter Wimsey detective stories, Sayers (1893-1957) was also a Christian humanist, dramatist and translator. She considered her translation of Dante's La Divina Commedia as her best work. She was two-thirds finished translating Paradiso when she died suddenly.

Sayers was the only child of an Anglican minister and his wife. Her father was the chaplain of Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford, England, when she was born and later moved the family to Bluntisham, where he was the rector of the small church near the Fens. That church and the new bells he procured for it inspired one of Sayers' most popular detective stories, The Nine Tailors.

Her parents nurtured her love of religion, reading and later the theater. Her father taught her Latin, French and German. But during her adolescence and young adulthood, Sayers became troubled by dreary liturgies and the hypocrisy she found in the church.

As a teenager, she wrote poems mocking religion. "The Gargoyle," for example, makes fun of ministers and their boring sermons as it speaks of a preacher who "Spouts at his weary flock" and preachers who can be "awful dampers when they're dry."

In her 20s, Sayers wrote "The Mocking of Christ" (1918), a poem that satirizes people who believe Jesus endorses their political causes. As she grew older, her writing captured how disturbed she was by individuals who believed the goal of faith was to protect cultural traditions. It especially concerned her that those who executed Jesus were people "painfully" like us.

She disdained Christians who practiced "exchangism," thinking that God would treat them well if they said certain prayers. She disliked ugly stained glass windows, milquetoast Christians who lacked imagination, poorly written homilies and saccharine religious art. Bothered about people caring more for social status than with the Nicene Creed, she argued that it was essential for Christians to be familiar with the dogma contained in the creeds and especially that derived from the first four ecumenical councils of the church.

Honored to write a play for Canterbury Cathedral, which in 1937 had presented T.S. Eliot's play, "Murder in the Cathedral," Sayers wrote "The Zeal of Thy House," which was first produced in Canterbury in April 1938 and was highly successful. She found playwriting inspiring as she saw the effect of actors delivering her words to the audience.

Advertisement

This led her to develop her concept of the importance of work and of the nature of the creative process in her most significant book, The Mind of the Maker (1941). Here, she discusses what it means to make almost anything, from a garden to a poem, in ways that correspond to the dynamic relation among the three persons of the Trinity in Christian theology explaining how the activity of one illuminates the activity of the other.

Downing's 2016 book probing Sayers' work, Writing Performances: The Stages of Dorothy L. Sayers, argues convincingly that Sayers has been largely overlooked by the academy because she wrote detective stories, bestsellers and religious drama.

The title of Downing's latest alludes to the subversive nature of Christianity, the revolutionary life of Jesus Christ, as well as Sayers' own life and work — shocking for the times. (Today, having Jesus and the apostles speak in everyday English, as Sayers did, wouldn't cause the stir it did in the 1940s and '50s.)

In providing context to Sayers' oeuvre, Downing makes connections to present-day circumstances, but, unfortunately, she is vague and lightly brushes over names and situations. Downing also refers to circumstances in her own life, which at times seem a stretch and beside the point. She is at her best when she discusses brief excerpts from Sayers' letters and essays as well as several of her books and plays, including "The Zeal of Thy House," and "The Man Born to Be King."

After she ended her career as a mystery writer, Sayers focused on Christian drama for stage and radio. As Downing suggests, she returned with a new understanding to her childhood faith: that faith had played down Jesus Christ's subversive personality, making him seem like a goody two-shoes and fashioning his crucifixion, the most dramatic event in all of history, into something boring. How could this happen? If Jesus Christ was true God and true man as stated in the Creed, then his crucifixion and death amounted to the murder of God.

As Sayers sees it, the fault lies primarily with parishioners' little knowledge of church dogma and sacred Scripture and with preachers who, emphasizing Jesus' humanity, have turned "the Lion of Judah" into a household pet with a sweet disposition when in reality he was the most radical, shocking individual ever to live. He was not crucified, as Sayers explains, because of his kindly nature. He was put to death because he was a threat to the status quo.

Yet, Christians, Sayers says, are not called to denounce the murder of God. They are called to celebrate it "by witnessing to the fact that the crucified Jesus was God Incarnate." This is the ultimate message of Lent.