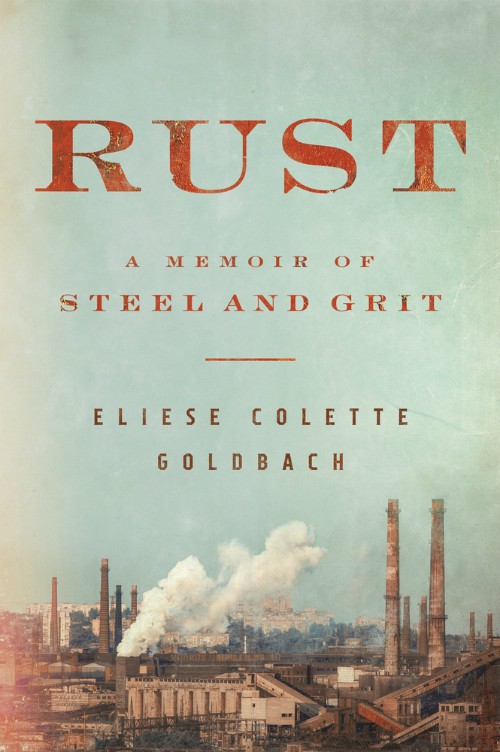

View of the ArcelorMittal steel mill in Cleveland, 2016 (Flickr/Roy Luck)

Since 2016, we have witnessed the rise of what Appalachian public historian and activist Elizabeth Catte has called the "Trump Country" genre. The Trump Country genre attempts to explain Trump's election to coastal liberals by describing the allegedly "backwards" cultures of Appalachia or the Rust Belt.

Catte has criticized this genre for its oversimplifications and misrepresentations. The genre obscures the fact that Trump enjoyed support from wealthy and middle-class white voters across the country, not just from working-class white people in "backwards" regions. The genre presents the working class as a white, male, union-laborer monolith, instead of a politically and racially diverse, largely female class of service industry and gig economy workers. And it often repeats "culture of poverty" rhetoric — blaming the alleged personal and cultural deficiencies of poor people, instead of exploring structural and systemic problems.

It is impossible to define this genre without reference to J.D. Vance's Hillbilly Elegy, its most successful and notorious example. And it is to Hillbilly Elegy that Flatiron Books, in its March 3 press release, compares Eliese Colette Goldbach's debut book, Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit.

Eliese Colette Goldbach (Michaelangelos Photography/Cheryl DeBono)

Rust offers a liberal take on the Trump Country genre, written by a Rust Belt native and former steel worker. Goldbach is a millennial feminist from a lower-middle-class Catholic Republican family in Cleveland. Growing up, she was told that a college degree was the ticket to a good job, that she could grow up to do and be anything. She believed it. She aspired to travel the world, to earn at least one doctorate, to become a nun.

Rust charts Goldbach's journey of coming to terms with, and overcoming, common realities of millennial young adulthood: graduating and trying to enter the workforce during the Great Recession, crushed by student debt and unable to find work that pays a living wage or offers the basic benefits that were commonplace when many of our parents' generation were young.

Goldbach rents a small, rodent-infested apartment that smells like dead animals. She struggles to make ends meet as a house painter. Suffering with untreated bipolar disorder, Goldbach confronts the realities of health care in the United States: dreading losing parental insurance coverage at 26, unable to afford Plan B as she fears a possible unwelcome pregnancy, enduring the callousness of health care professionals when she does seek help.

The memoir is set in Cleveland, but in those above ways, it could be set nearly anywhere in the country. What could not be set anywhere in the country is what follows: Goldbach's ticket to stability in the form of a well-paying union job.

Goldbach's work at the steel mill provides the backbone of her memoir. In her descriptions of the mill, her talents for evoking atmosphere and creating a layered sensory world on the page are on full display. She conveys the sights, smells, heat and exhaustion of her work. She also conveys the depth and complexity of the mill's emotional and social landscape — the pain, strength and humor with which workers confront the dangers of the job, the solidarity that holds even between workers who don't like one another, the pride she and the others feel in their steel worker identity and community.

The paychecks pull Goldbach out of poverty. Strong union protections allow her to keep her job, afford consistent treatment and receive accommodations for her mental illness, after the sharp return of her symptoms brings her to the emergency room and a short psychiatric hospitalization.

The change in her material circumstances gives Goldbach the stability to manage her bipolar disorder and reckon with the effects of its likely environmental trigger, her rape by two men during her first year at the Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio.

In her discussions of rape and its aftermath, Goldbach demonstrates the same skill in bringing the reader into her world that marks her stories about the mill. She captures the ways in which community betrayal — victim-blaming, denial and minimization — can be nearly as traumatic as the rape itself. She describes the devastating effect of the rape on her Catholic faith, and she bravely describes Steubenville's then-president Franciscan Fr. Michael Scanlan's revictimizing response to her after her assault.

But while Goldbach discusses systemic issues, she also repeats individualist notions of personal willpower and the American dream, sometimes suggesting that moving beyond self-pity and choosing to take risks were ultimately the key to her healing and success.

Advertisement

Though Goldbach does not disparage the working-class people of the Rust Belt — instead emphasizing their grit, decency and generosity — she does seem to argue, consistent with this individualist streak, that they are held back by their own fear and inability to overcome personal obstacles. She cites her father as one example. Goldbach mentions but does not explore the anti-Trump views of some of her fellow union workers. She focuses instead on those who supported Trump, arguing that he exploited and appealed to their fears, instead of appealing to their many admirable qualities.

Where I expected Goldbach to offer an alternative political vision, she instead seemed to argue for transcending politics by attending to the positive individual qualities of the Trump voters in her life. The most remarkable example of this came after her description of a sharp exchange with her Trump-supporting father about the "Access Hollywood" tape. She said she didn't see how any Christian could support a man like Trump. Her father waved off Trump's comments as "locker room talk." When she asked him how he and her mother could vote for Trump when she, their daughter, was a rape survivor, her parents fell silent.

It is a remarkable and powerful moment. But Goldbach resolves this tension quickly, arguing that her parents' personal support and sacrifices on her behalf — exemplified in their finding her at the hospital after her suicide attempt — represent who they really are, and that their political differences are unimportant by comparison.

This represents one weakness of an otherwise moving and well-written memoir: At times, Goldbach seems to suggest that politics is somehow less "real" than individual behavior in relationships. But both things — the political and the personal — are true at the same time, and both have real, concrete consequences. If Goldbach wants her memoir to speak effectively to our current moment, it is not enough to say that we should transcend politics. Why not offer an alternative political vision, informed by Goldbach's feminist and union worker values, to the fear and hate-mongering vision of Trump?

That said, Goldbach is a talented writer who weaves together remarkable descriptions and reflections on mental illness, poverty, rape culture and her Catholic childhood, and I look forward to her next book.

[Kelly Stewart is a doctoral candidate at Vanderbilt University, where she studies trauma theory and Catholic theology.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.