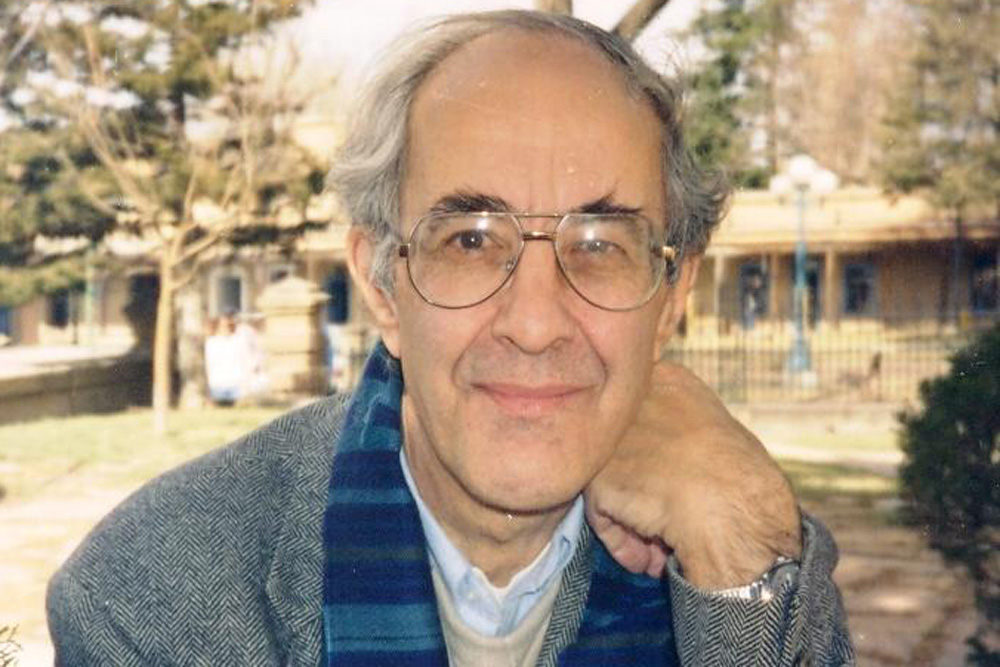

Fr. Henri Nouwen, pictured in the 1990s (Wikimedia Commons/Frank Hamilton)

Today's priesthood stands on shaky ground. Just who and what is a Catholic priest? Since the Second Vatican Council, priests have struggled to come to terms with the implications of the council's focus on baptism as the central, core and foundational sacrament of the Christian life.

The ordained priest, like all the faithful, is called by his baptismal incorporation in the Christian family to discipleship and witness to the saving Gospel of Jesus Christ. And he meets this call not as one set apart, but as a servant leader embedded in the very heart of the Christian community. This fresh emphasis on baptismal dignity and identity has been nothing less than transformational for priests, a true turning point in their understanding of the vocation to priesthood. In this return to the sources, resourcement, the council challenged the priest's sense of identity as one set apart from the nonordained people of God.

Henri Nouwen, like most post-Vatican II priests, eagerly embraced this liberating status as a fellow pilgrim amid God's holy people. For other priests deeply anchored in their identity as men set apart by ordination, the post-conciliar "reform of the reform" has served to reinforce their hold on their priestly identity as distinct and privileged. For these priests, they are indeed set apart. And in many different ways — sometimes explicitly — they are saying, "Please remember I am a priest and please address me as 'Father.' "

On top of the identity issue, priests are coping with the once hidden but now seemingly relentless reports of widespread sexual abuse of minors by a relatively small but significant number of their ordained brothers and bishops. With a thunderclap, the curtain has come down on the Catholic stage where the pastor and curate long held the leading roles in the unfolding drama of parish life. The once accepted script — "Father knows best" and "Whatever you say, Father" — has been shelved for good.

And underneath the identity issue, priests find themselves more and more off balance in a growing secular age where large segments of the population, including Catholics, scratch their heads at the notion of transforming grace or the healing power of the sacraments. The laity are no longer docile. And for many Catholics, the clergy are no longer perceived as admirable and inspiring men. Mothers once proud to have a son a priest are not so sure today. The demographics are clear — the majority of priests carry Medicare cards, and the seminaries that educated and formed them are in many dioceses shells of what they were a half century ago.

Clearly, today's priesthood stands in need of reform.

Michael W. Higgins and Kevin Burns agree, and in their new book, Impressively Free: Henri Nouwen as Model for a Reformed Priesthood, they make their case. I am afraid it is not a strong one. Their book covers the life story of Nouwen, his vocation to the priesthood, and his extraordinary career as a gifted spiritual writer, charismatic teacher and lecturer, and sometime missionary. The authors are at their best when they reveal Nouwen's inner struggles and near frantic search for a sense of home — for community and intimacy.

Franciscan Fr. Alberto Gauci visits children July 22, 2014, at an orphanage he helped build in Juticalpa, Honduras. The Franciscan priest has served in the area for the past 31 years and completed public works projects, despite having limited resources. (CNS/David Agren)

A surprise gift from the Netherlands, Nouwen's star rose swiftly after his arrival in the U.S. as a public mystic and spiritual guide to countless seekers. Blessed with supportive and cooperative archbishops of Utrecht (Cardinals Bernard Alfrink, Johannes Willebrands and Adrianus Simonis) where he was ordained in 1957, Nouwen moved without much difficulty from psychiatric and psychological training at the Menninger Foundation in Topeka, Kansas, to teaching posts at the University of Notre Dame, Yale and Harvard. He enjoyed unusual freedom as a diocesan priest and moved easily in and out of short terms of monastic life to visits to South and Central America and beyond. His meeting with the famed Jean Vanier, founder of L'Arche, led to his final years at the L'Arche Daybreak community in Richmond Hill, Ontario. Here, living simply with mentally and physically challenged adults, Nouwen hoped to find the community and home he had been searching for all his life, and the deep, human intimacy that had eluded him for so many years.

Only in Chapter 8, "The Harvard Years: A Crisis of Identity," and only for a few pages, do Higgins and Burns address Nouwen's homosexuality. This is unfortunate, since it is fair to assume that much of Nouwen's intense internal turmoil and restless searching were linked to his mostly unknown sexual orientation. From the standpoint of his sexual neediness and unwillingness (fear? prudence?) to go public with this core part of his identity, Nouwen was impressively unfree.

His good friend Peter Naus commented on Nouwen's struggles with his sexuality. "What I remember very well is his agony, and my deep compassion for the situation in which he found himself because I already knew that at that time it would be extremely difficult for him to 'come out of the closet' so to speak." Today's gay clergy, the vast majority of them deep in the closet, understand Naus' compassion for his friend. The question comes to me, is Nouwen a model for gay priests and bishops? And I answer yes and no. From his unflinching commitment to bear witness to Gospel freedom and to "the glimpses of God that I have been allowed to catch," Nouwen is indeed a model for gay clergy — and for straight priests and bishops. For gay clergy longing to come out of the closet, I think not.

While I don't believe Nouwen is a model for a reformed priesthood, I do think of him as witness to the courage and imagination required of priests today. I remember being captured by his passion for Gospel freedom and transformation when I heard him lecture at the University of Notre Dame and later when he spoke to priests of my home Diocese of Cleveland. Nouwen's great gift was his ability to speak and write from his contemplative heart. In doing so, he bore witness to the ability (and skill) necessary, absolutely necessary, for priestly ministry — the ability to connect.

Advertisement

Catholics come to trust, respect and love their priests only when they feel humanly connected to them. Clericalism, a deep tear in the fabric of the church, thrives on the negative energy of priests who fail to connect. Nouwen's humanity and transparency (with the exception of his homosexuality), his compassion and courage, forged his stunning gift for connecting with his readers in the deepest corners of their hearts. And this makes him a witness — and in this sense, a model — for priests who share his passion for humble, priestly ministry in our wounded church and world.

Moreover, Nouwen might have a lesson for priests laboring under the pressure of polarization in their parishes, chanceries and in the wider church. Perhaps the best way to avoid the energy-sapping divide between Catholic progressives and traditionalists is simply to move around it. Nouwen never took it on. His focus remained on the radical freedom of the Gospel and the transforming power of the Spirit.

Higgins and Burns capture a Henri Nouwen who was both heroic and tragic — courageously free and tragically restricted in openly owning his sexual identity. Yet he remains, in all his complexity, a witness to committed priestly ministry.

In spite of its organizational and copyediting flaws, Impressively Free merits the attention of priests. Without question, Nouwen, dead these many years, has a wise word for his brother clergy.

[Donald Cozzens is the author of the award-winning The Changing Face of the Priesthood. His latest books are novels, Master of Ceremonies and Under Pain of Mortal Sin.]