Richard Holbrooke, U.S. State Department special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, testifies during a hearing in late July 2010 on Capitol Hill in Washington. (CNS/Reuters/Molly Riley)

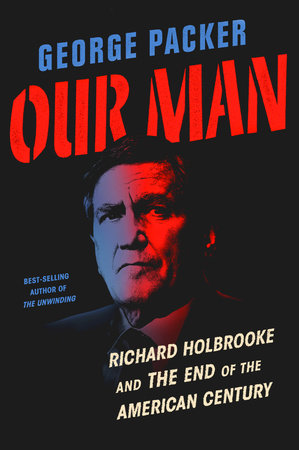

The old saw, "You can't tell a book by its cover," is sometimes misleading. In the case of Our Man, George Packer's intimate biography of the late mid-level diplomat and ambassador Richard Holbrooke, its cover is a blend of horror and sci-fi visual signals, neon colors and scary typefaces, plus a threatening picture emerging from blackness of Holbrooke himself.

And, though it isn't quite a compliment any longer to say a 608 page nonfiction book "reads like a novel," Packer's book does, given its literary method, which echoes a number of fictive forebears (Packer has published two novels himself), but the one that rings in my ear is the narrator of The Great Gatsby.

There, Nick Carraway recounts Jay Gatsby's life. Carraway, it is often forgotten or not known, is a young establishment figure, a Yale graduate, a bond salesman, and, one assumes, a success to be. Gatsby is the mysterious self-made man. This parallel mimics Packer, Holbrooke's junior by some 20 years, who also went to Yale, and became a friend and promoter of Holbrooke. And, like Gatsby, Holbrooke can be said to be a self-made figure, though one who as a boy had access to the State Department figure Dean Rusk's household through Rusk's son, a classmate. Like Gatsby, there was a change of names in the Holbrooke family.

Holbrooke, though, was mostly formed by joining the Foreign Service at an early age, a suggestion of Rusk's. Holbrooke shed wholesale his parents' rougher Jewish refugee biography (his mother favored the Quakers for him), though retaining enough get-up-and-go to forge ahead. Like a number of public figures who achieve, Holbrooke lost his father when he was a youth and acquired a lifelong attachment to powerful, older men.

I have read and reviewed any number of biographies, and Packer's is one of a kind. It brings to mind Edmund Morris's Ronald Reagan bio Dutch, but its effects were more bizarre, Morris creating actual fictional characters within its reads-like-a-novel conceits. Our Man burrows from within. Packer's narrative voice, like Nick Carraway's, assumes more friendship than there might have been, but Packer's portrait of Holbrooke's life is fueled by extensive research as well as a "friend's" personal knowledge. It is a fraught, but enlightening, combination.

Our Man is divided into 3 sections, Vietnam, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Holbrooke's notable foreign bailiwicks; Packer's portrait is painful reading, especially for Catholics, starting with his piteous examination of Holbrooke and the Vietnam War, which, then and now, seems so much like a religious war, given the antagonists. There is little separation of church and state when it comes to past and contemporary conflicts, though the religions often switch around.

Holbrooke was 22 in 1963 when he went to Nam and he championed hawkish American exceptionalism, the popular project among influential liberal public intellectuals, and most of the Washington, D.C., establishment.

The Cold War anticommunist ethos went largely unquestioned during the Vietnam War till the end of the '60s and, as Packer's book outlines, while the brutal spectacle of Vietnam unfolded, Holbrooke may have begun to question our country's methods, but never its aims. Indeed, the ideology was a core belief: it's what a powerful state does, have its way with lesser countries, especially given our purported good intentions.

Much later in Holbrooke's life, before starting an affair with a young colleague, Packer describes Holbrooke kissing her unbidden: "He claimed her in the way of an entitled great man." Similarly, the belief of political entitlement loomed so large for Holbrooke, he never questioned it.

During the Vietnam War none of the men running it wanted to be "tainted by the talk of peace," as Packer puts it. In 1967 these were the older men Holbrooke cultivated to advance in the State Department: Dean Rusk, Nicholas Katzenbach, W. Averell Harriman, Walt Rostow, Cyrus Vance, Robert McNamara, the names go on, as do Holbrooke's relationships with them. His contemporary, Les Gelb, Packer writes, "had never set foot in Vietnam. His ignorance was nearly complete — he'd read just one book on the subject, Bernard Fall's The Two Viet-Nams — and yet for two years he drafted regular memos on the war that went from the secretary of defense to the White House."

Packer makes clear that it was a young man's (person's) war, both in the dying and in the enabling, making the official gears run smoothly. Holbrooke, after nearly two years in country, left Vietnam and went back to Washington, D.C., to help himself rise and court the men who ran it. Packer doesn't bother, hundreds of pages later when Iraq emerges, to mention all the twenty-somethings that were dispatched to Baghdad after our invasion to run that show, along with Henry Kissinger's lackey, L. Paul Bremer, another Foreign Service creature, born the same year as Holbrooke, who was made Iraq's chief executive in 2003. Not much had changed at the top during those intervening four decades. By the 2000s, the Cold War, after 9/11, had become the Constant War.

Packer's book provides, as journalists say, all the ticktock of the martial events of Holbrooke's lifetime (ditto his social and financial life). His greatest achievement, Packer acknowledges, was Holbrooke's sort of ending the war in Bosnia (the so-called Dayton accords). Here most of his defects, well documented by Packer, became virtues, not vices, since he was dealing with monstrous figures and Holbrooke could match them crudity for crudity.

Advertisement

It's all there in Packer's volume, ending with Holbrooke's unhappy and unsuccessful attempts to "end" the war in Afghanistan during the Obama administration. Packer's multi-page description of Holbrooke's death is a tour de force itself, though that can be said of a lot of his book. Our Man might be the leading edge of the new modern biography, since so many books written about public figures in the past often hid the relationship of the author to the subject, rather than highlight it.

Nonetheless, Our Man is the most depressing and illuminating volume about contemporary American history I have read in years. Like the book's jacket art, it's a mixture of horror (the never-ending wars and slaughter) and science fiction (the amazing technologies deployed in their name).

[William O'Rourke is a Professor Emeritus of English at Notre Dame; his new book, Politics and the American Language: Reviews, Rants, and Commentary, 2011-2018, will appear in the Spring.]