Detail of a plaque depicting St. Paul and his disciples from around 1160-80 made of champlevé enamel and copper (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Christianity's growth in the decades after the crucifixion is a narrative seeded with mysteries. The early accounts of Jesus as Christ, as savior, spread in the late 40s A.D. through the travels, preaching and writings of Paul. The apostle who never met Jesus encountered his spirit as Saul, famously thrown off his track of persecuting believers in Jesus.

Here we are, some two millennia later, with questions begetting questions over the way Christianity branched out from small home-church enclaves. How did the earliest Jesus-believing Jews attract a nucleus of pagan gentiles? How should we square Paul's writings with the four Gospels, written more than a generation later, after the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem in the year 70? What impact did the convulsions of Judaism in the Roman world, in the time between Paul's early writing and that of the Gospel authors, have on the embryonic Christians?

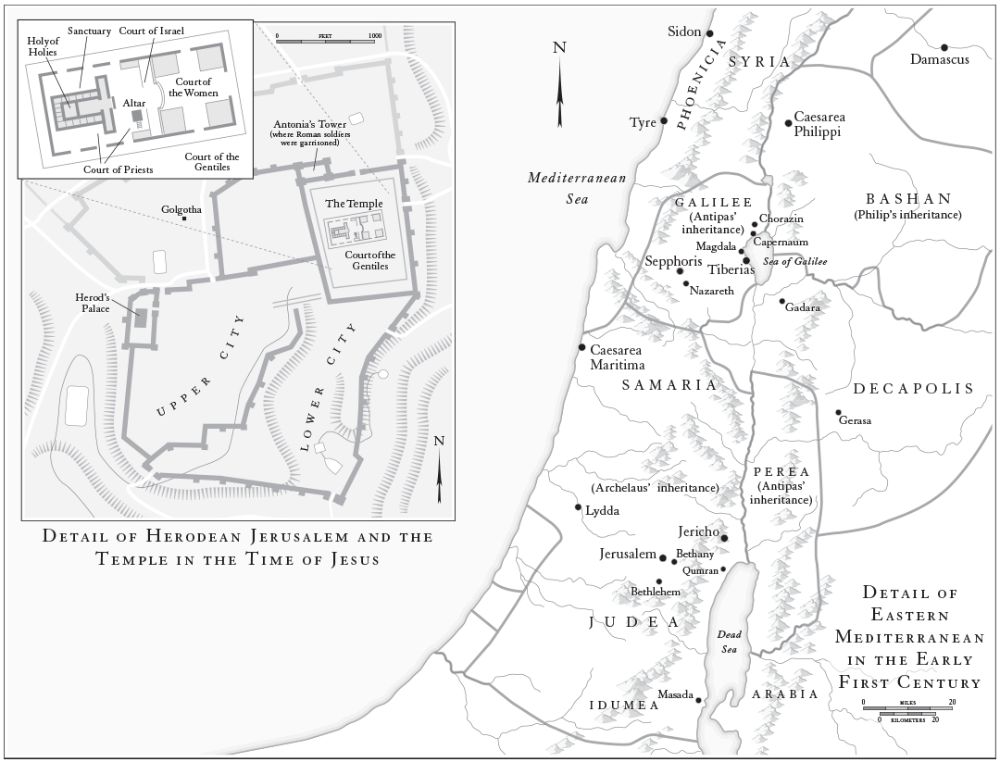

The building of the great temple under the Roman ruler, Herod the Great, who died a few years before Jesus' birth, gives context to When Christians Were Jews, the latest work by the distinguished Scripture scholar Paula Fredriksen, a Boston University professor emerita and faculty member at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Not least of this book's abundant virtues is the author's thoughtful questioning of just how the Christian movement gathered ferment.

Herod, the tyrannical master builder of Judea, gained control over the appointments of Jewish leaders at the temple, using murder when necessary to install supporters. And yet, writes Fredriksen, "Centuries after its destruction, the rabbis — no fans of Herod — would still recall, 'Whoever has not seen Herod's temple has never seen a beautiful building.' "

After Herod's death, tensions grew between Jerusalem's high priests and Roman rulers, the years in which Jesus came of age. How much time Jesus actually spent in the temple is unclear from the four Gospels. John "depicts Jesus frequently in Jerusalem," but as Fredriksen cautions, the scene when he clashes with the money changers in the temple "does not inaugurate events in the final week of his life and has nothing to do with his eventual execution. Dramatically, the scene goes nowhere."

Advertisement

Rising tensions between Jewish rebels and subsequent Roman rulers were a shadow through Jesus' lifetime and beyond, unto the cataclysmic destruction of the temple a generation after his death. Yet neither John the Baptist nor Jesus "seems to have linked his prophecy to a call against any political leader," writes the author. Jesus' agenda of mercy and radical witness for the poor and marginalized did not extend to rebellion against Roman rule.

Paul carried the message to early believers in distant places like Corinth: Christ would return to raise the dead and establish the Kingdom of God, shaping a literal belief that the followers were living at the end of time. Paul knew Peter, James and other aging followers who had personally known and followed Jesus. It is tempting to imagine what the core of early apostles thought of the zealous Paul, pushing the boundaries of a faith they were struggling to advance according to their own experiences.

The Gospel writers who followed Paul experienced the temple's destruction as a touchstone, a sign of the Kingdom forthcoming. Fredriksen asks: "If Paul himself throughout his letters proclaims the signs of the coming Kingdom to his own communities, then why does Paul evince no knowledge of Jesus' prediction" of the fallen temple?

Only seven of Paul's letters survived; most of his correspondence was lost, yielding no sign of whether he predicted the destruction of the temple. The sense of epic loss had a traumatic impact on Christians of Jewish background as an apocalyptical sign, the Endtime at hand.

"The eventual but lengthening absence of the raised Jesus, despite the continuing charismata of community members, would have begun to force them to reassess the significance of [Jesus'] posthumous appearances," writes Fredriksen. "Clearly, the raised Jesus was not about to inaugurate the Endtime, because the Endtime, bafflingly, continued not to come."

Map from "When Christians Were Jews," depicting details of Herodean Jerusalem and the Eastern Mediterranean region (Yale University Press)

Taking the message from the shattered holy city of Jerusalem to Diaspora outposts in Judea and beyond, the early evangelists "still worked, they were convinced, within a brief period, that tick of time between Jesus' resurrection and his definitive, final return. The resurrection appearances, as the community interpreted them once they had stopped, clearly did not signal an immediate End. They signaled, rather, an impending End. It was within that gap between Jesus' resurrection and his definitive, final, triumphant appearance at and as the End … that the community now lived."

The impact of the Roman war against Jerusalem from 66 to 73 A.D. colors Mark's Gospel. During his last Passover in Jerusalem, Jesus sits with several disciples on the Mount of Olives, overlooking the temple, prophesying, "Do you see these great buildings? There will not be left here one stone upon another, that will not be thrown out." He goes on to say that the "gospel must first be preached to all nations" before the end comes. False prophets will rise up to lead people astray. This, for an audience numbed by the destruction of the temple and witness to pagan sacrifices on the holy mountain.

Luke, the later Gospel author, "breathes not a word about the turmoil and trauma caused by Caligula, even though he sets his story about Jerusalem's community precisely during the middle decades of the first century. … This fits Luke's overall calming effect on the apocalyptical traditions that he had inherited." Writing in the early second century, Luke had the benefit of hindsight over Mark and Matthew. "He did not see his age as laboring toward history's finale."

Late first-century Jewish warriors continued battling Roman troops and overlords, as recounted in the chronicles of Josephus, Tacitus and Suetonius, which Fredriksen mines in reminding us how the Gospel accounts of Jesus developed in an era of bloody turmoil. Nero's murder ended the dynastic rule of emperors; civil war followed. Against this background, the writing of the three Gospels before Luke's cast a long light back on Jesus' lifetime and a belief of the imminent Kingdom.

"What happened to this earliest original community of Christian followers?" asks Fredriksen. "Did they perish in the flames of Jerusalem? Perhaps some did. A fourth-century church tradition, however, relates that they fled the city before the Roman siege."

The irony of the survival of Torah-observant Jews who embraced Christ is that three centuries later, their beliefs were denounced as heresy by Jerome, writing after the conversion of Constantine. In the fourth century, as Christianity assumed the role of a state religion, interpretations arose "against the Jews" and became "one of the drive-wheels of patristic theology," notes Fredriksen.

"It is useful to ponder the fact that, by Augustine's period, James, Peter and Paul would have all been condemned as heretics."

It is useful, too, in weighing the cautious lessons of When Christians Were Jews, to ponder how theological divisions in today's church, over issues of sexual morality and a scandal-battered hierarchy, will look several generations hence, after continuing migrations driven by war and violence, as believers in overcrowded cities yearn for a Gospel truth.

[Jason Berry is the author, most recently, of City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300.]