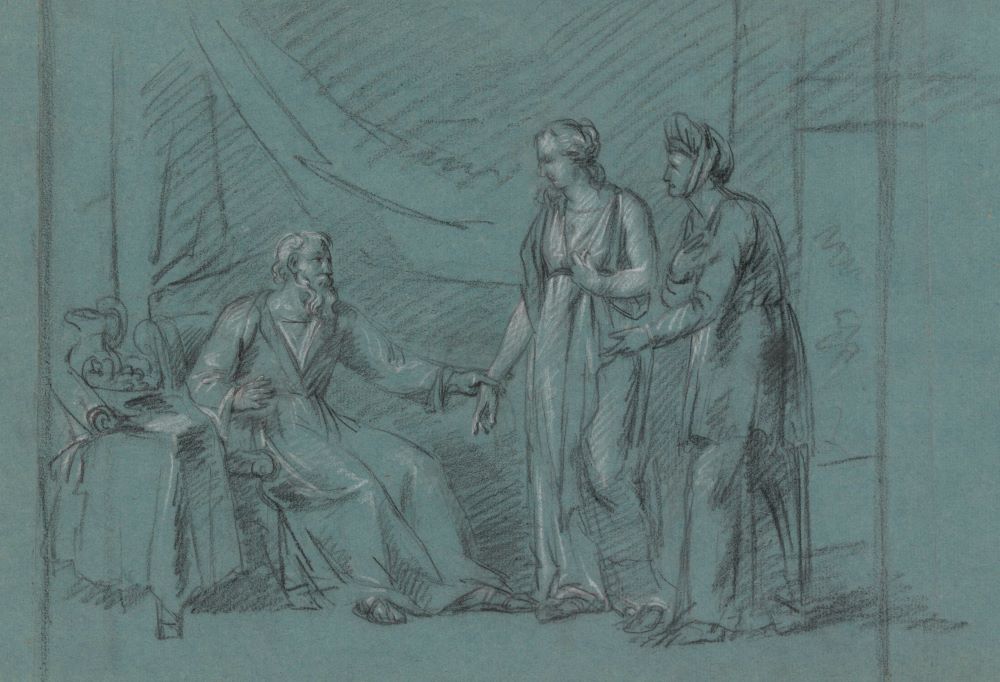

"Sarah Presents Hagar to Abraham," a drawing by the Belgian artist Jean Antoine Verschaeren (1803–1863), depicts a story from the Book of Genesis. In "Sisters in the Wilderness," Womanist theologian Delores Williams uses this story to illustrate Black women have been unavoidably shaped by the problems and desires of those who oppress them. (Artvee)

It has been 30 years since womanist theologian Delores Williams introduced readers to the historical — and dare I say continued — plight of Black women through the biblical archetype of faith, Hagar, in her book Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk.

For Williams, this history, when reread in light of the biblical account of Hagar, illustrates that Black women have been unavoidably shaped by the problems and desires of those who oppress them. It is the lens of motherhood by which Williams seeks to explore what she describes as the struggle between power and powerlessness in human relationships that disrupt peace in family units, breeds enmity between women (and men), and sends poverty-stricken slaves — in this case, a female slave — scurrying into society's "wilderness."

Williams finds the closest parallel to the Hagar story and the experience of historical and contemporary Black women in Hagar's experience of surrogacy. While Hagar's surrogacy was primarily biological, Williams notes that for Black women, their experience with surrogacy has primarily been associated with social-role exploitation. This has looked like coerced surrogacy — the ways in which social and political systems more powerful than Black women were used to force her into roles that were both physically and sexually exploitive during the antebellum period — and voluntary surrogacy, which involved participation in some of the most strenuous areas of the work force, including domestic work as "mammys" for white families.

"Hagar And Ishmael in the Desert" (1851) by Luigi Alois Gillarduzzi (Artvee)

Coining the term "Wilderness Theology," Williams asserts that Black women, within the context of the larger Black community, have asserted their dignity/personhood via their insistence on survival. She explains that for many Black women, the wilderness symbolizes an experience of being utterly alone in the midst of agonizing pain with only God to rely on for deliverance. Williams writes, " 'wilderness' or 'wilderness-experience' is a symbolic term used to represent a near-destruction situation in which God gives personal direction to the believer and thereby helps her make a way out of what she thought was no way."

But what exactly constitutes a "wilderness experience"? Williams explains that the wilderness is a deeply transformative and religious encounter consisting of a fivefold structure: isolation, the establishment of a relation, healing, transformation and a motivation to return.

Speaking to the historic realities of the enslaved, Williams explains that the experience of isolation — physical or otherwise — often necessitated the creation of a relationship between the afflicted and Jesus. Such encounters revealed situations of utter vulnerability and the need for deliverance by a source greater and outside of oneself. This recognition not only resulted in a form of healing, but ultimately led to personal transformation. The experience of conversion eventually inspired the afflicted to return to the community changed for the better. Although the wilderness became something enslaved persons were able to recontextualize, the experience was not without moments of intense suffering.

But the hope of the wilderness became the promise of nourishment by God's gracious gift of manna — i.e., Jesus Christ — who would ultimately transform the experience of suffering into one of survival and hope. Thus, William says, the "wilderness experience is suggestive of the essential role of human initiative (along with divine intervention) in the activity of survival, of community building, of structuring a positive quality of life for family and community; it is also suggestive of human initiative in the work of liberation."

Perhaps the most challenging and beautiful sections of the book includes Williams' treatment of the ministerial life of Jesus as inherently salvific and a picture of realized eschatology, along with covenant-relation as the assurance of completed promise.

The discussion of the ministerial life of Jesus opens with the observation that dominant interpretations of classical Christology emphasize a believers' redemption from sin through the cross of Christ who takes sinful humanity upon himself. Williams reads this as representing the ultimate image of surrogacy — which she finds problematic — attached to the divine personage of Christ suggesting its sacredness (Williams assuring us that it is not).

"Hagar in the Wilderness" (1835) bv Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (Artvee)

Instead, Williams asks whether the image of divine surrogacy — either coerced (willed by the Father), voluntary (chosen by the Son), or both — serves already exploited Black women and persons. For her, Black women and persons are not redeemed by exploitative divine surrogacy as articulated by traditional orthodox teachings on Jesus' life and death. Rather, they are saved through Jesus' life of resistance and the survival strategies he employed to help people survive a death of identity caused by an exchange of cultural meanings in favor of a new life marked by Gospel ethics.

Citing the Gospel of John, she asserts that the Spirit of God in Jesus came so that humans might have life and have it abundantly. Redemption via this perfect ministerial vision would emphasize the righting of relations between body (individual and community), mind (of humans and of tradition), and spirit.

Acts pointing to this vision include Jesus' raising of the dead, casting out demons, and proclaiming the good news to those most in need of it. He further achieved this vision through an ethical ministry of words (parables, moral directions/reprimands and the beatitudes); a healing ministry of touch and being touched (healing lepers, the blind, the woman with blood, etc.); a militant ministry of expelling evil forces (exorcisms and whipping the moneychangers from the temple); a ministry grounded in the power of faith (in the work of healing); and through a ministry of prayer, compassion, and love. The ministerial life of Jesus demonstrates the shift from an emphasis on the death of Jesus toward the question of survival.

By shifting our focus, Williams demonstrates that the ministerial life of Christ exemplifies the Gospel of John's claim that Christ came to give us life abundant. This does not negate the trauma of the cross nor the salvific ramifications of Jesus' death. Rather, the ministerial life of Jesus exemplifies his own participation in a life clearly imbued with the sacramental presence of God.

It is specifically Jesus' words to the woman with the issue of blood which I believe most demonstrates this, specifically that participation in the sacramental life is salvific. The Matthean text says that Jesus responds to the woman's plea for healing in this way: "'Take heart, daughter; your faith has made you well.' And instantly the woman was made well." In the Greek, the word translated as "well" is the verb sōzō which means to save or to keep.

The beautiful paradox of Jesus' own participation in the sacramental life is that he both acknowledges the hidden presence of God active and abiding in the world through his ministry of healing and teachings on being born of the Spirit, while simultaneously being the incarnated gift of God's own self-communication with humanity — echoing Karl Rahner's sensibility that this self-communication or grace is the very thing that governs and structures all of reality.

Thus, Jesus' active ministry reveals that his life as the self-communication of God on Earth is to be considered salvific along with his death and resurrection; they cannot be understood apart from each other. Indeed, is there anything that Christ does throughout the Gospels that is not salvific?

Is there anything that Christ does throughout the Gospels that is not salvific?

Williams' emphasis on Christ's ministerial life over and against the cross, death and resurrection serves as a corrective — and perhaps an over corrective — for the ways in which the narrative of the cross has been used to perpetuate violence against marginalized Black women. While I personally do not believe we need to emphasize one over the other — the two being intrinsically linked — Black women and anyone who finds attention to one facet unedifying should have the freedom to look to the other, deriving from it a sense of the saving power of God at work since both are faithful readings of the biblical text.

Williams ends this section of her analysis by stating that this vision of the kingdom serves as "a metaphor of hope God gives those attempting to right the relations between self and self, between self and others, between self and God as prescribed in the sermon on the mount, in the golden rule and in the commandment to show love above all else."

Finally, Williams points out that in the book of Genesis, covenant and promise are associated with survival, election and blessing. Just as God promises Hagar that her descendants will be too numerous to count (Genesis 16:10) and delivers her and Ishmael from death in the wilderness, it is the reality of promise — God's promises made to us in Jesus Christ — which seals our future hope in an assurance that one day our people, all people, will truly be free in Christ. In the meantime, we are to heed the words of the prophet Jeremiah who brings these words to the Israelites held in captivity:

Build houses and live in them; plant gardens and eat their produce. Take wives and have sons and daughters; take wives for your sons, and give your daughters in marriage, that they may bear sons and daughters; multiply there, and do not decrease. But seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.

Williams explains that we are not to interpret this text as God encouraging Black people to acquiesce to their condition. Rather, as oppressed Black Americans, we must choose the opposition of our genocide through acts of re/production and participation in the life of the community.

Advertisement

"The community must work [on] behalf of its survival and the formation of its own quality of life," she writes "[This] womanist survival/quality-of-life hermeneutic means to communicate this to black Christians: Liberation is an ultimate, but in the meantime survival and prosperity must be the experience of our people."

Williams concludes with the following assurance: this promise will be realized and emerge out of the witness of the Black church which is "the heart of hope in the black community's experience of oppression, survival struggle and its historic efforts toward complete liberation."

For me, the reality of promise entails the completion of the work of salvation which has already begun in this life and will carry over into the next. This is why we can affirm the words of the apostle Paul to the Philippians: "I am confident of this, that the one who began a good work among you will bring it to completion by the day of Jesus Christ."

Promise does not excuse us from working toward bettering the community, as articulated in the Jeremiah text and several New Testament passages which indicate that we are to labor as if in a vineyard while we await the return of the master. Indeed, it is the very reality of promise that compels us to participation in the sacramental wilderness until the return of Christ Jesus.