A Muslim man is pictured in a file photo praying outside a mosque in Khartoum, Sudan. (CNS/Reuters/Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah)

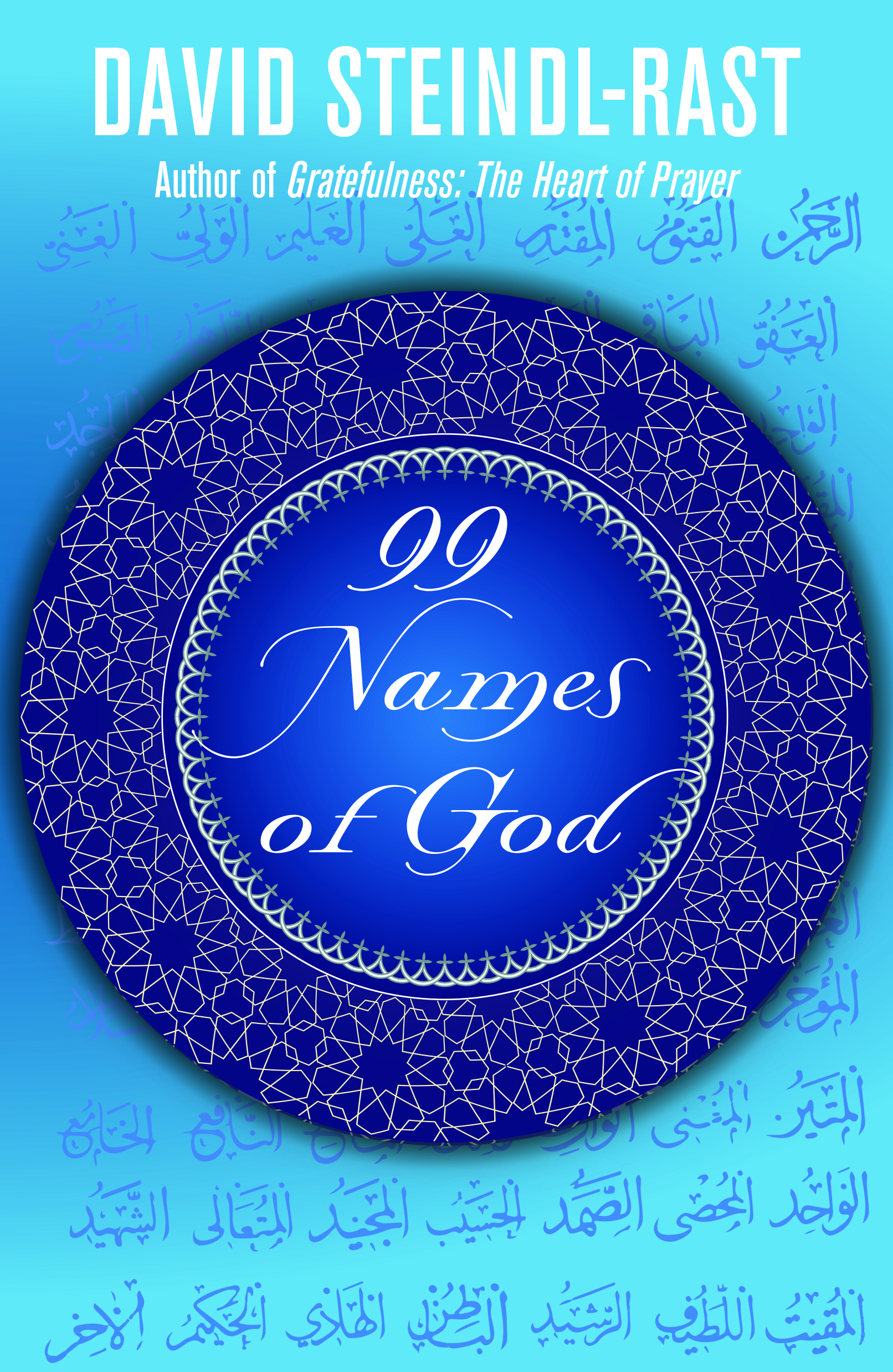

Islam is the world's fastest growing religion, embraced by one fourth of the global population and with three and a half million adherents living in the United States. Yet dialogue between Christians and Muslims is fraught, given differences in theology, ethics, history and contemporary political realities. Benedictine Br. David Steindl-Rast offers this slim book, 99 Names of God, as a beginning point for Christians to enter into the devotional life of Muslims in the hope of opening up dialogue between them.

Steindl-Rast is well positioned to do this. Born in 1926, he was awarded a doctoral degree in psychology and anthropology from the University of Vienna. He entered the Benedictine monastery at Mount Savior in Elmira, New York, in 1953 and was co-founder of the inter-religious Center for Spiritual Studies. Although best known for his writings on gratefulness, he has been engaged in interfaith dialogue since 1966, in both Christian-Buddhist and Christian-Muslim discussions.

His insight is that if Christians can explore a principal devotional ritual of Islam, namely repetition of the Koranic names of God, this will give them a starting point to appreciate what can seem like a strange and inaccessible religion to some Christians. All three of the Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — are "people of the book," each has a written scripture and all name God.

Steindl-Rast is clear about why humans name. In their encounter with God, who is understood as "Thou," they make clumsy attempts to address and call by name the transcendent yet intimate reality. He attests that this naming expresses the human experience of God, but only indirectly the Ultimate Reality encountered. All these 99 names are related and connected but none singly or together can capture God. Steindl-Rast analogizes these names both as a prism that refracts God's resplendent beauty and as windows onto God's mystery.

Some of these names of God derive from human intellect and reason, including the "almighty," "the powerful," "the sovereign." Others arise from the intimacy of the encounter, such as "the merciful, "the compassionate," "the ever-forgiving." The devotional purpose of repeating these names is to bring one closer to the encounter that produced them. Naming is a stammering attempt to "call to" Ultimate Reality experienced as "Thou." Christians should find here a ritual practice familiar to them.

Advertisement

It is evident that Steindl-Rast has used this ritual practice of praying 99 names as a way to enter into the mystery of God. In this devotional volume, each of the 99 names is rendered in Arabic, English and calligraphic form. Because Islam does not allow any visual depiction of Allah or Mohammad, calligraphy serves as a major expression of religious devotion. Steindl-Rast explores each of the 99 names, interprets each for Christians and then gives a prompt for further reflection. His intent is not to collapse Islam into Christianity or vice versa, but rather to appreciate that Muslims too encounter God, and like Christians their naming is a way to enter into the nameless origin of all. He urges Christians to pay attention to this Islamic devotional ritual in order to make them ready for dialogue.

God is the "First without Beginning" and "The Last without End," "The Giver of Life," and "the Bringer of Death." God is "The Steadfast," "The Faithful," "The Self-giver." God, "The Nourisher," prompts us to be grateful for what has been given to us and to nourish others. God, "The All Wise," is the one who affirms seemingly paradoxical contradictions. God, "The Most Gracious," urges our total dependence and spurs us to be gracious to others. God, "The Holy One," heals and is merciful and brings us to acknowledge both our flawed nature and the ability to allow God's holiness to stream through us. God, "The Compassionate," shares our suffering and our passion. God, "The Guide," is close to us as we search for direction. God, "The Creator of the New," grants us a role in realizing our unique potentiality.

It is evident that Steindl-Rast has used this ritual practice of praying 99 names as a way to enter into the mystery of God.

As a man who has given his life to speaking across religious divides, Steindl-Rast exhorts Christians to open themselves to inter-religious dialogue. He writes:

For most people this inter-religious dialogue will be something that they only read about, because they have no opportunity to engage in it. … If you are interested in promoting the inter-religious dialogue — which I think we should be interested in … then we should expose ourselves. Exposure is the key word. All the people who have been exposed to other traditions — really exposed and not just told about them and not just made fearful about them — "meet" somebody who is from a different religion. So make a special effort to "meet" other people from other religions.

He offers the 99 Names of God as the beginning of that process.