Brazilian troops occupy Presidente Vargas Avenue in Rio de Janeiro April 4, 1968, for a requiem Mass in memory of Edson Luís, murdered by gendarmes seven days earlier. These events were part of a series of building-up tensions between the people against the regime that led to a further toughening of repressive polices by December. (Wikimedia Commons/Brazilian National Archives/Correio da Manhã)

No end-of-an-era announcement accompanied news of the recent death of Bishop Pedro Casaldáliga, but that would have been appropriate. He was the last of three bishops in Brazil who demonstrated extraordinary leadership for decades under the most trying of circumstances.

At a time when evidence of things gone wrong with the Catholic hierarchy threatens to overwhelm so much else, Casaldáliga, as well as Cardinal Paulo Evaristo Arns, who died in 2016, and Archbishop Dom Hélder Câmara, who died in 1999, stand apart as exemplary servants of the Gospel and their communities in the most threatening conditions and among some of the most marginalized on Earth. We would all do well to revisit their lives and example at a time of global fear and uncertainty.

Hailed in death as displaying saintly qualities — in fact a sainthood cause has been opened for Câmara — in life they often bore the deeper, hidden wounds inflicted by church authorities who questioned their motives, their theology and their allegiance.

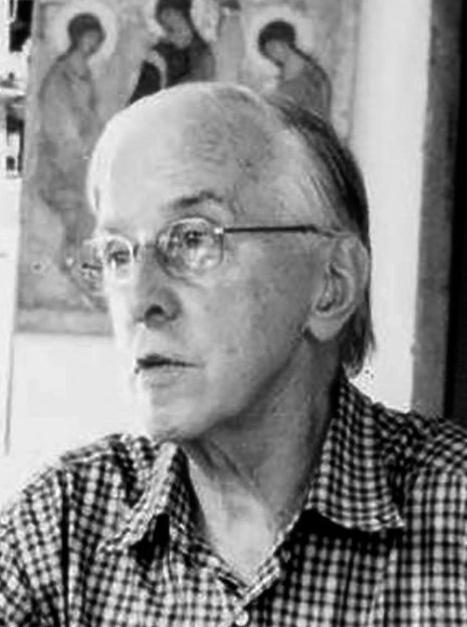

Retired Bishop Pedro Casaldáliga in an undated photo. (CNS/Courtesy of São Félix Prelature archives)

Unswerving in their advocacy of human for rights during Brazil's 21 years of oppressive and brutal military dictatorship (1964-1985), the three also had to fend off denunciations by powerful figures in the Vatican apparatus during the 1980s and '90s. It was an apparatus assembled by Pope John Paul II, hastily sainted in death, who was, in the words of long-time Vatican journalist John L. Allen Jr., simultaneously "the apostle of unity ad extra and the bruiser ad intra."

Arns, in conversation with writer Lawrence Weschler about the growing authoritarianism in John Paul II's Vatican, remarked, "This Polish pope, he is our cross to bear."

The bruises John Paul meted out to fellow bishops, theologians, various thinkers and activists, could be deep and debilitating. Reputations were trashed by those in the bureaucracy he put in place in the service of an absolutist approach to his highly personal ideas about order and discipline.

The institution changed, as it always will, and that brand of severe discipline has faded. The broader church, then, should consider what survived, what is seen today as the best expression of the heart of the Gospel.

The three Brazilian bishops led dioceses through a hellish period of social upheaval in that country, a time of mass disappearances, torture and death. Câmara led the Archdiocese of Olinda and Recife the entire length of that period, from 1964 to 1985; Arns headed the Archdiocese of São Paulo from 1970 to 1998; and Casaldáliga was bishop of São Felix from 1970 to 2005. No one would have blamed them for taking refuge behind the chancery walls. Instead, they walked into the center of the storm with those most at risk.

During the period of terror, Arns was in and out of prisons, keeping track of those termed enemies of the state. He called out the government over the assassination of a journalist, held religious services in defiance of the dictatorship, provided space for the beginnings of a worker movement and secretly collaborated with ecumenical partners and international agencies to gain access to reams of documents that described the horrors of torture and killings. Those pages became a compiled record titled "Brasil: Nunca Mais" (Brazil: Never Again).*

Advertisement

I first met Arns in the mid-1980s, knowing then that he was celebrated for having confronted the dictatorship and having advocated for the poor of his diocese in extraordinary ways. He endorsed liberation theology and had accompanied his Franciscan friend, theologian Leonardo Boff, to a session before the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), where Boff was questioned about his writing.

At a convention of the Catholic Press Association, he summoned me to a corner of one of the rooms and showed me a letter from the CDF silencing Boff. "For 21 years I worked for the right to free expression," he said, referring to the work he had done to maintain communication throughout his diocese during the period of dictatorship. "And now my brothers in Rome are doing this."

In 1991, during my first visit to Rome, I had an opportunity to witness the degree of hostility at least one influential figure in the CDF expressed toward Arns and Casaldáliga. At the time, I was news editor at Religion News Service (RNS), and the purpose of the visit was to simply get a basic understanding of how things worked in the Eternal City. A more experienced Vatican journalist who sometimes filed for RNS arranged curial meetings, and one of them was with a U.S. priest who worked at the congregation.

Cardinal Paulo Evaristo Arns in an undated photo (CNS/KNA)

As the conversation began, my associate mentioned Casaldáliga, who for some reason I no longer recall was in the news that week. As I've previously written in a 2003 NCR column, that mention "evoked a torrent of invective and vicious language." He referred to Casaldaliga and Arns by name and labeled them "ignorant little men" who were "naïve."

I remember thinking at the outset of his bizarre tirade that perhaps this was a set-up arranged by the priest and the Vatican reporter to shock the newcomer from America. But it didn't take me long to realize that he was quite serious.

I met Câmara once, briefly, prior to an event in New Jersey where he was receiving an award. It was toward the end of his life. I recall it as an encounter with a remarkable persona. One of those individuals about whom it is easy to conclude: He is whole, complete, absolutely at peace with himself. It was also easy to conclude that it is nearly impossible to do a productive news interview with someone who has clearly and authentically become a mystic.

Câmara, known for his radical insistence that the church stand with the poor, was known as "the bishop of the slums." He is quoted in a biography as having said, "When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist."

Arns, at his death, was hailed as "the cardinal of the people" and celebrated for his relentless work for human rights. At an event observing his 95th birthday, a former justice minister noted his "courage and prophet-like fearlessness, and his teachings rooted in the Franciscan values of the apostles."

Bishop Don Helder Camara at a Eucharist celebration in Den Bosch, the Netherlands, Oct. 27, 1974 (Wikimedia Commons/Dutch National Archives/Hans Peters)

Casaldáliga, who lived in austere circumstance, was called the "bishop of the poor" and described by the Brazilian bishops' Pastoral Land Commission as "a reference for citizens from all over the world who fight for democracy, for those who dream of a more just and egalitarian world."

The priest I met in the CDF office has since gone to his maker, and I can only presume for his sake that he was acting in what he believed the best interest of the church. But the tantrum I witnessed, I've realized since, was a shrill religion stuck in its fear of the unknown.

The example of the lives of the three bishops in Brazil is, by contrast, that of an enduring, mature faith willing to take steps into the unknown. Arns, Câmara and Casaldáliga, each in his own way, embraced a holy vulnerability that required they loosen their grip on certainty and absolutes.

U.S. Catholics, bishops included, facing a growing segment of the population marginalized by the consequences of a pandemic and other social and political challenges — loss of wages, food insecurity, homelessness, assaults on voting rights, and renewed hostility toward people of color — could do worse than to reflect on the lives of Arns, Câmara and Casaldáliga. They were neither ignorant nor naïve. Fools for Christ, perhaps, but we view such foolishness as saintly.

[Tom Roberts is former editor of NCR.]

*Editor's note: The title of the book ""Brasil: Nunca Mais" was incorrectly translated as "Brazil: No More." It is correctly translated from the Portuguese as "Brazil: Never Again."