St. Peter's Square, the Vatican, Rome (Unsplash/Caleb Miller)

Last week, the Lumen Christi Institute at the University of Chicago hosted an event about church governance entitled "The Open Question of Church Polity: Trent, Vatican I and Vatican II." I was not able to find video of the event yet, but in searching for it, I came across video of an event sponsored by Lumen Christi last year that touched on the same theme but with a more explicit focus on Vatican I. That event was entitled, "Vatican I: Loss and Gain with Papal Governance of the Catholic Church."

At a time when questions are being raised about the viability of the Catholic Church's current model of government, both events were a timely reminder of the array of issues involved, and the seriousness with which those issues must be engaged. Today, I shall focus on the event last year and will look forward to video of last week's event.

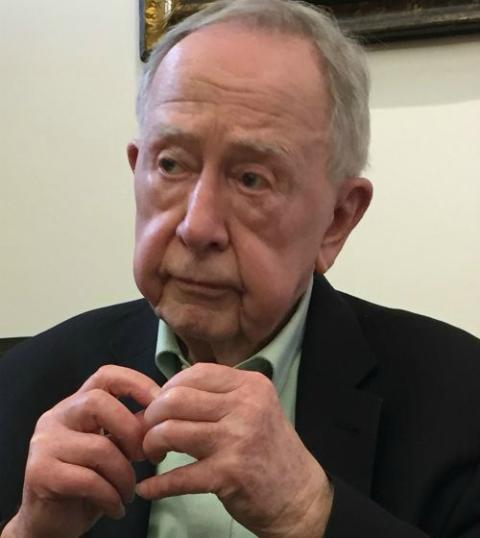

Jesuit Fr. John O'Malley, Jan. 24, 2018 (CNS/Cindy Wooden)

Jesuit Fr. John O'Malley explained that by the end of the second century, bishops were responsible for the governance of the local church and, by the end of the third, the bishop of Rome was given a special status. In the 11th century, popes began to exercise increasing degrees of governance over the universal church. The papacy was notably weakened in the 18th century, epitomized by the death of Pope Pius VI in custody at century's end. As well, by the time Vatican I opened, the centralization of authority had become pronounced in civic governance, "it was required by the culture in which we live," O'Malley said. Papal governance also highlighted the universality of the church, giving concrete expression to the Lord's command to go out to the ends of the earth baptizing and preaching, as well as counteracting what O'Malley termed "an almost rabid nationalism" that characterized the 19th century, if not always effectively.

O'Malley touches on one of the ironies of history I have noted before, namely, that anti-Catholic governments often strengthened the papacy unintentionally. For example, even though the Catholic Church condemned the separation of church and state until Vatican II, the fact that the U.S. Constitution enshrined it prevented the U.S. government from exercising any role in the selection of bishops, and that power was placed entirely in papal hands. The anti-clerical government of the French Third Republic in 1905 abrogated the concordat that had given the government a prominent voice in the selection of bishops, again leaving the matter up to the pope. And so on. O'Malley rightly notes the importance of new communications technologies in also making the pope a more visible presence throughout the Catholic world.

This change, O'Malley points out, meant that while the spiritual goals of the church need never be hindered by the political goals of a particular government, the selection of bishops was now entirely in the hands of clerics. Kings and queens and emperors were, after all, members of the laity. I think the more important point is that the involvement of governments added a local counterweight to Roman authority that probably served a moderating role. And, most royals saw their role as divinely ordained, and so I question the degree to which the fact that they were lay altered the landscape.

In any event, and as O'Malley notes, whatever the strengths or weaknesses of the old system, there is no way to bring it back.

The role of the papacy as a "theologian-in-chief" emerges from the Ultramontane movement and specifically Pastor Aeternus, the dogmatic constitution on the church, adopted at Vatican I. Although not technically linked to papal primacy in other areas, this change had the effect of weakening the episcopacy and strengthening the papacy. It should also be noted it was the truncated constitution, because the council was interrupted by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, and so the council never got to discuss and promulgate Catholic teaching on the episcopate. O'Malley rightly notes that St. Thomas Aquinas never systematically dealt with the concept of papal teaching, still less cited it, because there were no encyclicals back then. This is an issue that will continue to require examination: The chair of Peter is many things, but it is not a faculty chair.

O'Malley concluded his talk with the assertion that it is "axiomatic" that good governance is most likely to emerge when there is a balance between the center and the periphery. He believes the tradition has the resources to achieve this balance, because it is collegial as well as hierarchical in structure.

Advertisement

Russell Hittinger, who is currently scholar in residence at Lumen Christi, pointed to the difficult history of the Council of Trent's disciplinary canons on marriage, which demanded the presence and blessing of a priest for validity, among other changes. Some civil governments saw this as a bridge too far and refused to permit publication of the canons. They were only universally applicable after Vatican I, 300 years later! The image of an all-powerful papacy in the Middle Ages or at the time of the Reformation is bosh. Hittinger had much else to say, and I encourage people to watch his intervention in its entirety as well as the response to both presentations from Jesuit Fr. Joseph Mueller of Marquette University.

My purpose today is merely to point out that advocates for changes in church governance, often growing out of proper indignation at the way the hierarchy has handled — better to say mishandled — the clergy sex abuse crisis, need to consider the theological and historical reasons the church is structured the way it is and be honest about the dangers their proposals portend.

So, for example, after the forced resignation of Buffalo Bishop Richard Malone, Terry McKiernan, co-director of BishopAccountabilty.org, said, "Rome has allowed and enabled the slow-motion train wreck of a great American diocese." In May, the pope gave local metropolitans the responsibility to request authority to investigate allegations made against a suffragan bishop involving sex abuse and covering up such abuse.

Russell Hittinger, 2009 photo (CNS/Eastern Oklahoma Catholic/Dave Crenshaw)

All summer, I kept expecting New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan's office would make an announcement he had requested permission to open such an investigation. I do not know why he failed to do so. It was Rome that finally intervened in October, dispatching Brooklyn Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio to conduct an apostolic visitation. In less than three months, Malone was ousted. This was the third such visitation in the U.S. ordered by Pope Francis, all of which ended in the removal of the bishop. (Memphis and Kansas City were the others.) Is that dereliction of duty? And, by the way, the pope hosted a synod during that time.

Tim Busch, the plutocrat who thinks he knows how to fix the Catholic Church, is suddenly in favor of lay leadership. Busch's Napa Institute is a hotbed of opposition to Francis. Is that the kind of lay leadership we think will help the church? Or the kind offered by Carl Anderson at the Knights of Columbus? Do progressive Catholics have the organization or money to compete with these conservatives if lay people were ever to gain more control over the church?

The governmental influence in the selection of bishops that O'Malley described also introduced specifically political considerations into the process. Does anyone think involving the laity today would not have the same result? In commenting on the often capricious behavior of Queen Anne in his book Marlborough: His Life and Times, Winston Churchill commented, "Royal favour was like the weather. It was as useless to reproach Queen Anne with fickleness and inconstancy as it would be to accuse a twentieth-century electorate of these vices."

In this environment, in this country, at this moment in history, it is irresponsible and reckless to be beating the lay leadership drum. Those who prattle on about the problems with "bishops investigating bishops" should get serious and explain what alternative they think is better.

Need one point out that in this decade, the Catholic hierarchy, for all its dysfunction, produced Francis to lead the universal church? Our vibrant democracy produced President Donald Trump. I'll take my chance with the hierarchy, thank you very much.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.