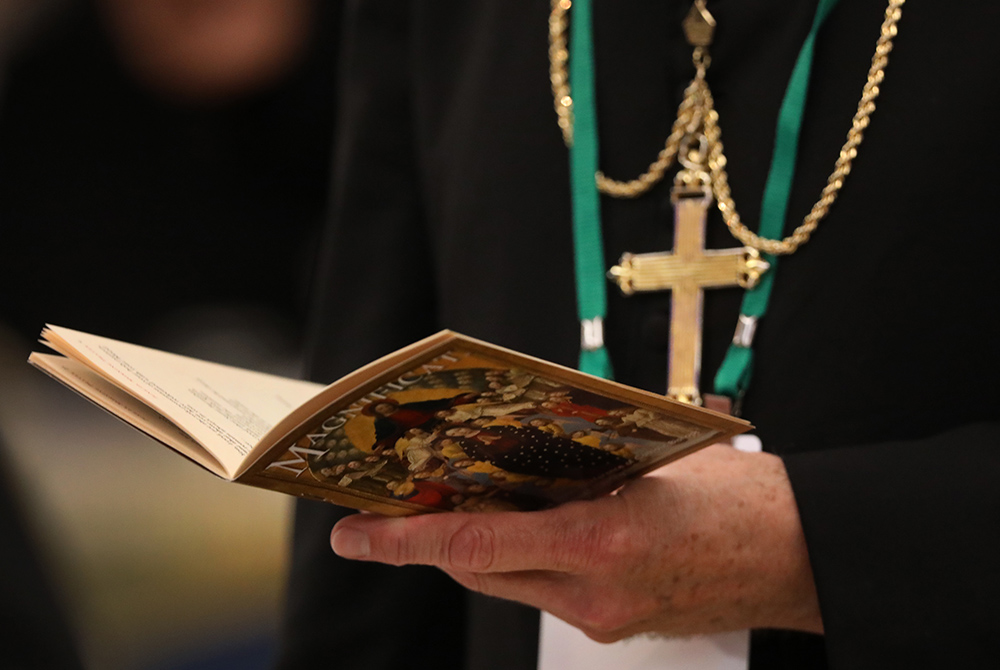

A bishop prays on the first day of the annual general assembly of the U.S. bishops' conference June 11, 2019, in Baltimore. (CNS /Bob Roller)

One of Pope Francis' most frequent themes is the need for greater empathy in our modern cultures — and in our Catholic church too. Way back in 2014, when the Holy Father addressed the Asian bishops in Korea, it was a central theme of his talk. And it runs through his most recent encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, as well.

This is not always easy. In an interview with Tucker Carlson, former Archbishop of Philadelphia Charles Chaput complained that some bishops had been "too compliant" with government-ordered restrictions aimed at stopping the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Really? I seem to remember bishops scrambling to fund and manage pop-up food pantries for the millions of people who were suddenly unemployed. I remember priests volunteering to bring the sacraments to people in hospitals and nursing homes and scrambling to figure out how to livestream a Mass. I remember bishops working with civil authorities to urge people to be cautious, to reopen schools safely and to maintain social distancing at all Masses, all in the interest of the common good. The excessively petulant Chaput sees only another culture war battle. It is the only lens he has.

Still, there is no denying that at a time when spread-eagle capitalism and libertarian mores have led many to espouse a new version of social Darwinism, Pope Francis' call to empathy should be heeded. And, for those of us who are U.S. Catholics in this moment — when some of our bishops wish to take the culture wars to the next level and make it an official teaching of our church that a politician should be denied Communion on the basis of his or her stance on public policy issues — empathy demands that we view those with whom we disagree in the most favorable light.

So, today, I should like to defend the culture warrior bishops.

I need not repeat at any length my many disagreements with those bishops who demand a document on "eucharistic coherence" and seek to deny President Joe Biden Communion. They misconstrue sacramental theology. They reduce the mysteries of faith to the demands of politics. They seem to yearn for a world that has vanished and was never as much of a Golden Age as they nostalgically recall. Their moralism blinds them to basic Catholic ecclesiology. These are points I have made in recent weeks here, here, and here.

What needs to be said on their behalf is twofold. First, that they are right about abortion being a great evil. I do not see how denying Biden will help bring abortion to an end. I do not think the bishops are the least prepared for the backlash that will greet them on the morrow of the Supreme Court's overturning Roe v. Wade. I do not think that making abortion illegal will do more to lower the abortion rate than would increasing access to affordable health care and providing women with the support they deserve to raise a child.

Still, those of us on the left all have friends who are a little too quick to make excuses for pro-choice politicians, a little too willing to raise bogus arguments to muddy the waters, a little too eager to change the subject. Those bishops who are leading the charge to deny Biden Communion are wrong in their choice of method, and their arguments are deeply flawed, but their horror at the loss of life brought about by the scourge of abortion is not wrong.

Second, the bishops are also right that the legal denial of rights to any class of human beings should make all of our moral alarm bells go off. The analogy between abortion and slavery on this point fails because we do and should express empathy with a woman facing a crisis pregnancy, while we do not and should not feel such empathy with a slaveholder. But the analogy is not entirely wrong either. Anytime a society says that one group of people do not enjoy the same rights as the rest of the people, something in the society is morally askew and great evil lurks.

This is especially true when one considers the rapid decline in the number of children born with Down syndrome. I remember the first time I started researching the politics of abortion before Roe for my first book. Survey after survey indicated that fetal abnormality was one of the most frequently cited reasons people thought abortion should be permitted. I was horrified. This had a whiff of eugenics even before advancements in prenatal testing allowed us to detect Down syndrome or other disabilities in utero. Now that whiff is a stench.

I sympathize with a parent for whom the prospect of raising a special needs child seems overwhelming, and pray for a day when our society would provide all the support needed to help a family in that situation. Eugenic solutions are evil. Full stop. And yet, hidden behind the libertarian claim that no one can tell a woman what to do with her body, eugenics has become a daily occurrence in our country.

A week from today, the U.S. bishops will begin their virtual meeting and they will discuss the issue of denying Communion to pro-choice politicians. Its advocates will say that if they fail to proceed, the Catholic Church's commitment to the pro-life cause will be in doubt. Bosh.

Advertisement

Every bishop in America agrees that abortion is a great evil and that no human person should be denied the equal protection of the law. All agree with Pope Francis that abortion is evidence of the "throwaway culture" at its most evil. All are frustrated that these moral truths have been obscured even among many Catholics. But not all agree that the way to vindicate these moral concerns is to begin denying Communion to politicians who, for whatever reasons, oppose criminalizing abortion.

Moral indignation can be understandable, even appropriate, but it is not a theology or a political strategy. By thinking it is such a strategy, the "no Communion for Biden" bishops mimic the moral compass of the Twitterverse. There are other morally significant challenges in our day, and politicians who wrestle with those many issues — and with the often powerful interests that seek to obscure the moral stakes involved — should be helped, even pitied. I will not say there is no circumstance in which a politician might not so comprehensively trash our Catholic moral teachings that he or she should be denied Communion. If he or she were racist, xenophobic, indifferent to democratic norms, misogynistic, fascistic, as well as pro-choice, perhaps it would be necessary. That is not the situation in which our country and its bishops find themselves.

I empathize with the moral horror at abortion in this country, but the bishops need to do more than throw a tantrum.