Mass is livestreamed on Facebook by Fr. Tom Kovatch, pastor of St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church in Bloomington, Indiana, March 28. (CNS/Katie Rutter)

As the coronavirus epidemic stretches ahead of us for weeks, and probably for months, how will it affect the people of God? I am afraid that we will all get too comfortable in quarantine. As a Catholic theological ethicist, my thoughts turned first to the seven deadly sins.

My primary worry isn't sloth or even gluttony — I'm not worried about people spending all their time eating ice cream in yoga pants while binge-watching Netflix. And after all, it must be said that an excess of these activities could mitigate the dangers of lust and vainglory as we shelter in place. The temptation to inordinate sorrow seems more serious, as does the temptation to become frustrated and angry at one's fellow castaways.

The sin I am most worried about it is superbia. While it is often translated as "pride," the vice is better understood as excessive self-concern and egoism. To those afflicted with this vice, other members of humanity seem not only less worthy than themselves, but also less real. They don't really count when the chips are down.

Most people are sheltering at home with members of their immediate family, which can feed superbia, because it becomes a larger context for self-identity and self-concern. I am encouraged to care only about me and mine — my better half, my offspring, my progenitors. The quarantine teaches us to see others not as friends and neighbors, but as potential threats to our domestic units. We are encouraged to avoid them if possible. When forced to share any type of space with them, we immediately assess their potential danger as walking, talking, coughing, sneezing virus vectors.

Advertisement

These patterns of behavior are justified, of course, in a pandemic. But they may create habits that will cause moral and social trouble after the threat has passed. American society already manifests a proclivity to self-select into safe and comfy identity groups. In The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing Us Apart (2007), Bill Bishop describes the drive to live, work and worship with people who look, think and behave just like we do.

There is a similar proclivity in the church. Perusing the Catholic press, I noticed some conservative, home-schooling mommy bloggers admitting that the coronavirus pandemic hasn't changed their lives at all. An insight clicked into place: A small but vocal segment of the church has long treated the broader culture (and their fellow Catholics) as if infested by a moral plague. I suspect that this lifestyle choice is not an expression of Catholic sensibility but a distortion of it motivated by superbia. Of course, progressive Catholics have their own versions of self-clustering, too. But they tend to travel in their moral hazmat bubble suits, rather than stay at home.

Some might say that technology mitigates these temptations. After all, we all remain connected, but safely, virtually. It is true that programs such as Zoom and Google Hangouts can help us get our work done — I have been gratified by how well my online seminar is going. But they do not enable physical presence. That limitation is most apparent in stories of those dying in quarantine. Seeing a beloved relative's face on a smudged screen is not the same thing as holding her hand as she slips away.

But these technologies are not only limited, they can also be theologically dangerous. Zoom and Google Hangouts undermine a key piece of Christian anthropology: the embodied nature of human beings. These technologies allow us to treat one another as disembodied spirits. We see each other's faces, for a set amount of time. Then our spectral visit ends, and we are instantaneously back in our own private domestic settings. Only two of our five senses are engaged — and even then, we can mute ourselves to mask the sounds of our breathing and coughing, and we cover the camera so no one can see when we are bored or distracted. We are not confronted by the annoyances of one another's embodiment.

Fr. Tom Kovatch ends a livestreamed Mass that he broadcast on Facebook Live from St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church in Bloomington, Indiana, March 24. (CNS/Katie Rutter)

Once the crisis has finally abated, how do we reclaim our three-dimensional presence to one another, with all its possibilities and annoyances? How can the church help us reconstitute ourselves as an assembly of flesh-and-blood human beings, rather than a grid of faces on a computer screen?

Theology and ecclesiology have vertical and horizontal dimensions. The vertical dimension focuses on our relationship to God, while the horizontal concentrates on our relationship with other people, each of whom is made in God's image. While both dimensions are essential, one or the other may be more urgent at a particular point in the life of the church.

I would urge my fellow theologians — and our bishops — to prioritize the horizontal dimension after the coronavirus crisis comes to an end. The word ecclesia comes from the Greek — it is a compound of the prefix ek (out) and the verb kaleo (to call). We are called out of our own homes, our own lives, our own spaces, to assemble to worship as the body of Christ. After so long in isolation, we may need some encouragement and accompaniment to heed that call.

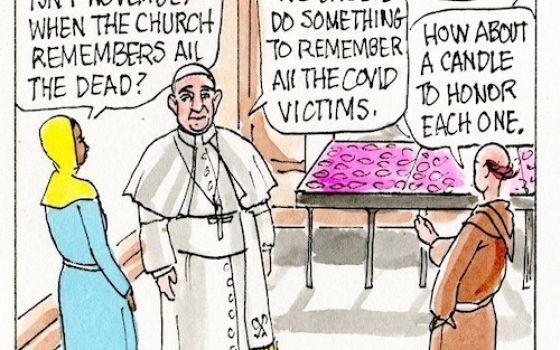

I consider Pope Francis' papacy to be a providential gift during these times. His theological anthropology is earthy, gritty and embodied. He prioritizes social connection and personal encounter. He has famously urged pastors to take on the "smell of the sheep." He urges us to go into the streets, to become present in the poorer sections of our cities, to share meals and work for the common good with those who live there. After the crisis has passed, there will be no justification for constricting our interactions to two of the five senses. Francis will remind us that the church is no place for antiseptic social distancing.

[Cathleen Kaveny teaches law and theology at Boston College.]