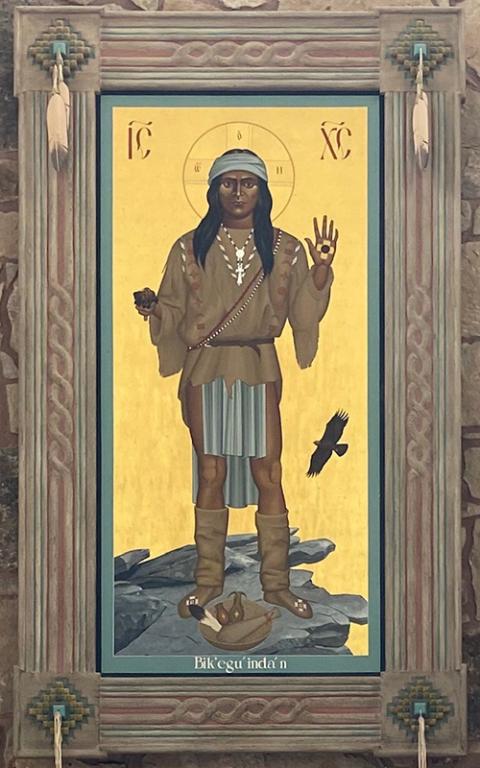

Fr. Dave Mercer, then-pastor of St. Joseph Apache Mission in Mescalero, New Mexico, stands at the altar during a first Communion Mass. Franciscan Br. Robert Lentz's icon "Apache Christ" adorns the wall behind Mercer. (Courtesy of Dave Mercer)

The recent removal of Franciscan artist Robert Lentz's painting, "Apache Christ," from St. Joseph Apache Mission, on the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico, has been rightly reversed. It is now a moment to consider the backstory for why this icon is so meaningful to our Apache friends. But first, a recent version of an old myth.

My Apache friend Marie and I were enjoying breakfast in Mescalero village when she told me of an experience that matched with the old myth of the Vanishing Indian and how it still confuses Native Americans. Marie (real name changed for privacy) had lived in the Carolinas for a while where she took night classes at a local college. A class discussion had touched upon Native Americans, when a student stated, "Oh … I thought Indians were all extinct." "Father Dave," Marie said, "how can people think that way?"

The myth long justified the replacement of Native American peoples with an ever growing Euro-American population. The former had simply vanished, and the children of Europe moved in.

"Apache Christ," painted by Franciscan Friar Robert Lentz, has been returned to St. Joseph Mission, a church on tribal land in Mescalero, New Mexico, parishioners have confirmed to OSV News. (OSV News illustration/YouTube)

Our country's storytelling is of a courageous people crossing the ocean and growing a society to become the biblical "city set on a hill" for all countries to be inspired by. Those early colonists landed on a continent that captured their Puritan view of a menacing world that did not know God. And, lurking in the dark forests around them were the godless Indians.

As the colonies grew, new settlers arrived, convinced they had a greater right to the lands. They pushed out and often killed the Native populations to populate the land. The line separating the children of Europe and Native populations moved further and further west. At one point, the children of Europe leapfrogged the Native populations to the West Coast and slowly pushed eastward. A myth developed of the Vanishing Indian which justified the growing Euro-American population where Native Americans once lived.

Our Native friends did not simply vanish, but lost their lands, and family members were killed, all in the name of the children of Europe having a manifest destiny to rule from coast to coast. Native cultures were of no real import. However, our Apache friends had a developed culture and worldview. They fought hard to preserve what the Creator had given them for their survival, and they were duty bound to protect it. Hollywood westerns never adequately depict that, for Apaches, the fight against the encroachment of whites and Mexicans was not just a battle for survival, but it was always a "holy war." Even the raids on passing wagon trains were surrounded with sacred meaning.

With the land being the Creator's gift, they experienced a Babylonian-type exile. In 1873, President Ulysses S. Grant established the Mescalero Apache Reservation. Not long after, a band of Lipan Apache refugees came to live with them. In 1886, the Warm Springs Chiricahua Apaches, led by Chief Naiche (son of the famous Cochise) and medicine man Geronimo, surrendered.

They were quickly taken by train to a Florida prison where children were forcibly removed to the famous Carlisle Indian Industrial School, and people were soon dying of tuberculosis and malaria. They then moved to a prison camp next to an Alabama swamp where more such suffering took place, before they were taken to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. As long as Geronimo was alive, the government would not consider releasing them. After nearly three decades, in 1913, they were released, but not allowed to return to their homelands near Arizona. (Arizona settlers would have revolted.) Instead, the Mescalero Apaches welcomed them to their reservation.

The exterior of St. Joseph Apache Mission in Mescalero, New Mexico (Courtesy of Dave Mercer)

Through it all, our Apache friends slowly became acquainted with Christianity. Their traditional spirituality was that of a practical religion, that is, it was how they lived in the land the Creator had given them. A sense of the sacred surrounded all aspects of life. Christianity, being missional or evangelical, could puzzle them. For example, their earliest contacts with Spanish Jesuit missionaries coming up from New Spain was typically at arm's length. They thought of them as witches, because, among other observations, Jesuits always had a supply of food, wore heavy black robes even during the hot summer months, and did not live with women. In the end, they decided to allow them to live, because the Jesuits were a source of food.

Their eventual surrender in the late 1800s was traumatic. They lost on the battlefield not because they did not fight hard. They lost to a superior technology. Keep in mind that boys grew into manhood with two primary responsibilities: to bring in the needed food and to keep their families safe. The worst thing to accuse a warrior of was to have betrayed his people. In a hostile world, survival was an everyday concern. You kill first or else your family is killed.

Advertisement

With defeat, they lost everything: the land and wildlife that the Creator gave them for their survival, the many family members killed, and the men, stripped of their primary purpose in life. Furthermore, there were no trauma intervention teams to help them cope with defeat and the subsequent despair. Everything seemed lost, and the inherited despair continues to be expressed in the higher rates of addiction and suicide. As with the Old Testament people after returning from exile, the cultural struggle of every generation has been not to vanish into history.

The first generations after defeat were forced to confront the dominant Euro-American culture, and many resisted, of course. As reservation life developed in Mescalero, the earliest Christian influence was from the Reformed and Catholic churches. Although some tribal members were baptized, follow-up pastoral care was sporadic, and most resisted the religion of the oppressor culture.

Franciscan Fr. Larry Gosselin celebrates Mass beneath the "Apache Christ" at St. Joseph Apache Mission in Mescalero, New Mexico. Gosselin is a former pastor of St. Joseph. (Courtesy of Dave Mercer)

Slowly, trust developed. Many saw common threads running through the traditional religion and Christianity: monotheism, mountain spirits were guardian angels, White Painted Woman was the Virgin Mary, and Child of Water was Jesus. A prominent tribal member could say that he had no problem with the Old Testament, it was what they believed, but he had no use for the New Testament because it teaches the love for one's enemies, which, in the hostile world they had known, could only be a suicide wish.

In 1916, Franciscan Fr. Albert Braun arrived and rode horseback along the trails to their camps, ate their food, slept on their ground and listened to their stories. And then, when the tribe's government agent and a Protestant pastor wanted to shut down the Apaches' blessing and coming-of-age feasts for being "pagan," Braun defended them, saying they were not "pagan." He invited the Bishop of El Paso, Anthony Schuler, to attend a traditional four-day puberty feast at Mescalero, and tribal member Eric Tortilla was the bishop's guide, explaining everything that was happening at the puberty feast.

At the end, Schuler stated that the feasts were not "pagan," but aligned with Catholic teaching about the sanctity and dignity of womanhood and the experience of bringing forth and nurturing life. Schuler then used many of his summer vacations to return to Mescalero and to help as an otherwise typical volunteer with the construction of St. Joseph Apache Mission.

"Apache Christ" is seen inside the church of St. Joseph Apache Mission in Mescalero, New Mexico. (Courtesy of Dave Mercer)

When work on St. Joseph Apache Mission began, sacred items from the Apache traditional spirituality were placed at the cornerstone, a clear statement that Apaches and their traditions are most welcome at the church. God (the Creator) had not forgotten the people. Years later, tribal president, Virginia Klinekole, looked back and said that her family chose to be baptized Catholic because of the great respect that Braun had shown for tribal traditions and sacred customs.

Yes, some missionaries were terrible in how they treated Native American cultures, but many were not. The best Catholic missionaries knew to leave alone what did not conflict with Christianity. Such was true with Braun and the largely Franciscan missionary legacy in Mescalero.

When Franciscan Br. Robert Lentz painted his "Apache Christ" icon, he did so with great care for Apache traditions and sacred customs and with dialogue with tribal spiritual leaders, the medicine men and women. With their approval, he painted Jesus as a medicine man, including symbols and sacred items for which our Apache friends needed no explanation. They understood the message that our Lord Jesus had been with them all along and that he is one of them as he is one with the people of every land. And, under his feet is the longtime Apache title for God: Bik'egu'inda'n, that is, Creator of Life.

'The Apache Christ reminds our Apache friends that they have not vanished into history.'

—Fr. Dave Mercer

Not long after I moved to Mescalero, I sat with my Apache big sister, Dortha, in the mission church in front of the "Apache Christ" icon, and said, "Dortha, that painting is stunning. I hope you never take it for granted." "Father, that will never happen," she said. "When it first went up on the wall, I sat here for the longest time." She paused … then continued: "I saw myself."

The Apache Christ reminds our Apache friends that they have not vanished into history.

"Apache Christ" is pictured inside the mission church. (Courtesy of Dave Mercer)

A few years ago, when former missionary and current bishop of Las Cruces, Peter Baldacchino, visited the Mescalero Reservation, I took him to a coming-of-age feast, where he witnessed the sacred dancing and singing. Taken into the sacred teepee, we accepted a blessing from the medicine man. When we were outside again, people noticed we were covered with the sacred pollen, and they nodded approvingly. The next morning, many were at Sunday Mass.

When we encounter a culture, its traditions and customs, and its art, and we do not understand something, it is not the time to remove or ridicule or label it as inferior. Instead, it is time to get on horseback with Fr. Albert Braun and ride the trails to their camps, eat their food, sleep on their ground and listen to their stories. It is time to join with Br. Robert Lentz and listen to those who safeguard their stories, symbols and sacred items.

We might find that our Lord is one of them. They might find themselves in God.