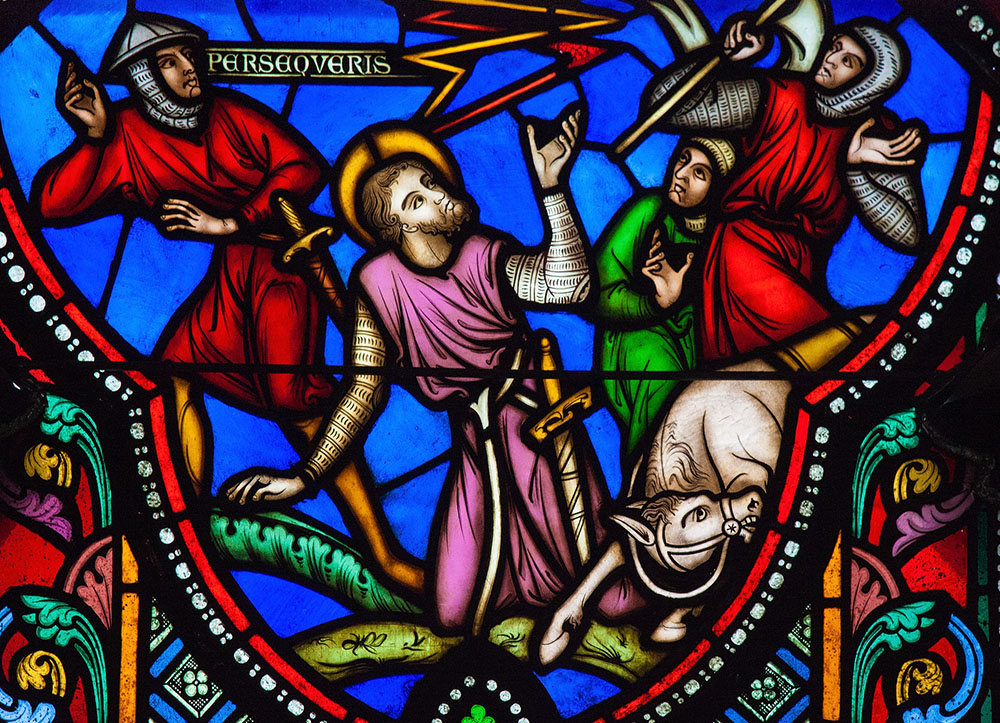

The conversion of St. Paul the Apostle in stained glass at the Catholic Cathedral of St. Gudula in Brussels (Dreamstime/Jorisvo)

Catholics love a good conversion story. Since the early days of Christianity, we have cherished the tales of saints, scholars and artists who entered the Catholic church as an act of radical departure from the lives they had lived previously. From St. Paul and St. Augustine in ancient times to St. John Henry Newman and Dorothy Day in the modern era, converts to Catholicism have left their mark on church tradition and shaped Catholic identity.

Today, we have our own lineup of noteworthy Catholic converts among clergy, religious, apologists and influencers. The world of Catholic apologetics, especially, is dominated by famous converts.

Many in Catholic audiences seem more compelled by the conversion story of someone who recently entered the church than by the perspectives of those who have been formed by it over a lifetime. This is not necessarily a bad thing, since newcomers can bring fresh outlooks, both personally and theologically.

However, we need to be careful about how we talk about this topic, given the church's morally deplorable history of forcing conversions, whether of Jews in Europe or Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Some who defend these forced conversions act as though Catholics are justified in using any means at their disposal, even intrinsically evil acts, to get someone into the church.

Advertisement

For instance, Declan Leary, a contributing editor to The American Conservative, wrote, in a 2021 article that the mass graves at residential schools in Canada should be viewed in a positive light, since they mean Indigenous children stolen from their families were baptized into the church before they died.

Even when we aren't forcing people into the church on pain of death or imprisonment, there can be a tendency for Catholics, and Christians in general, to take a consequentialist view, regarding people as potential "catches."

Pope Francis has rightly warned against a type of proselytization that is more like marketing the faith, or even coercing people into it. If the Gospel of Jesus is a message of liberation, forcing or cajoling people to assent to it seems self-contradictory.

Then there is the problematic trend of idolizing celebrity converts. Whenever a high-profile individual enters the church, there is a temptation to place that individual on a pedestal, while congratulating ourselves on having snagged an especially big fish.

When people who are best known for trolling, hate speech and abusive behavior are attracted to your in-group, it’s time to ask yourself whether they’re attracted to you for the right reasons.

Anyone joining a faith community should be welcomed with open arms, of course, but when celebrity converts are given special treatment, and fawned upon, this again runs counter to the teachings of Jesus, who viewed all people as equally sacred, and taught that the "last shall be first" and "the meek shall inherit the earth." When joining the church becomes a way to earn extra fame and fortune, conversion to Catholicism can almost look like a career move.

Lately, quite a few high-profile converts to Catholicism have been celebrated in media and politics. One of these is J.D. Vance, who converted to Catholicism in 2019, and recently won the 2022 race for U.S. senate in Ohio, over Democratic candidate Tim Ryan. As an Ohio resident and practicing Catholic, I closely followed the campaign of both Vance and Ryan. And I noted that many of my fellow Catholics in my area were quick to enthuse over the Catholicism of Vance while ignoring that of Ryan.

As NCR reporter Brian Fraga discussed in an article published only days before the midterms, Vance and Ryan represent two strikingly different forms of Catholicism. Ryan, the Democratic candidate, is a social justice Catholic, born into the faith and educated in Catholics schools. Vance, by contrast, is associated with "integralist" Catholics who believe the U.S. experiment with liberal democracy has failed, who seek to abolish separation of church and state, who tend toward nationalism, who oppose LGBTQ rights and racial justice initiatives, and who are critical of the pope.

Both Ryan and Vance had their enthusiastic Catholic backers. Catholics Vote Common Good, a grassroots nonprofit committed to the church's social teachings, campaigned for Ryan. Meanwhile, Vance was feted by leading Catholic integralists at a conference held at Franciscan University.

That Vance ultimately won the senate seat does not necessarily mean anything about the national influence of integralist Catholicism versus social justice Catholicism. It does, however, raise questions about why some Catholic converts end up getting the spotlight, especially when, like Vance, they ignore or even dissent from crucial Catholic teachings on racial justice, the rights of immigrants and refugees, and care for the Earth.

What goes on in the human heart is complicated. It is possible that a person could be genuinely attracted to the sacramental life of the church, or the richness of Catholic cultural heritage, and still hold views contrary to the teachings of Jesus and the church's social doctrine. Plus, conversion can be a lifelong, messy process, with lots of ups and downs along the way.

Yet Vance and other notable converts, such as anti-abortion activist Abby Johnson, alt-right personality Milo Yiannopoulos and most recently actor Shia LaBeouf, seem to be attracted less to the church founded by Jesus and the apostles, and more to a powerful institution that has, historically, sometimes allied with oppressors instead of with the oppressed.

As other Christian denominations change or develop their teachings on LGBTQ rights, contraception and the role of women in the church, the Catholic church can look attractive to individuals who enjoy ritual and tradition in a space where women are kept in the background and LGBTQ persons encouraged to remain in the closet. Far-right media personality Taylor Marshall and blogger Dwight Longenecker are both former Episcopalian priests who appear to have embraced Catholicism only because their original faith community was becoming too inclusive.

To what are these individuals converting? Are they really attracted to Jesus, the Gospels, the sacraments, the witness of the saints? Or are they attracted to the power associated with the church, and the opulence of traditional liturgy?

Perhaps these questions are too cynical. Perhaps I am giving insufficient credit to the mysteries of God's ways and the complexity of the human psyche. But, supposing these converts are genuinely drawn to truth and beauty, not to power and privilege, Catholic leaders and laity should be helping them divest themselves of their bigotries, for their conversion to be complete.

What kind of conversion is it, really, if one loves the Latin Mass and reading Aquinas, but hates God's children who are queer, immigrants or of different religions?

When people who are best known for trolling, hate speech and abusive behavior are attracted to your in-group, it's time to ask yourself whether they're attracted to you for the right reasons. Certainly, no one should feel that it's their right to march into the Catholic faith tradition with all their hate flags flying proudly.

What are we doing wrong, that so many decent, kind individuals are withdrawing from the church, while people who have made names for themselves through behaving cruelly are made welcome?

If people who have embraced bigotry, white supremacy and sexism wish genuinely to convert from their sins, this is a good thing, to be encouraged and celebrated. But if they are drawn to the church because they see it as a safe space for bigotry, this doesn't look like conversion. At least, it doesn't look like conversion toward Jesus.