Guatemalan President Bernardo Arévalo, center, and Vice President Karin Herrera, right, attend an Indigenous ceremony held in their honor at the sacred Mayan site Kaminaljuyu in Guatemala City, Jan. 16. a day after they were inaugurated. Arévalo was elected in a landslide in August. (AP/Moises Castillo)

Guatemala, so often defined by dysfunctional government and horrendous human rights abuses, has become a symbol of democratic hope, tenuous though it is, in a world where authoritarian models are ascendant.

The inauguration on Jan. 15 of anti-corruption reformer Bernardo Arévalo as the president of the most populous country in Central America is, in several ways, a full-circle moment. The Catholic contribution to this moment is, as you will see, formidable.

Arévalo's landslide victory in an April runoff election was described by The New York Times as "a stunning rebuke to the conservative political establishment" in that country. Time magazine saw it as "a rekindling of the revolutionary flame that once sought to transform Guatemala from a feudal autocracy to a more inclusive social democracy."

If the civil realm in our country has finally learned something from its long complicity in the suffering of Guatemala, so should the religious realm, especially the U.S. Catholic community.

That revolutionary flame was initially carried by Arévalo's father, Juan José Arévalo, an academic who became the first democratically elected president of Guatemala in 1944. The reforms he advanced in health care, education, labor and democratic rights were a sharp departure from decades of military dictatorship. Those reforms were advanced by his successor, Jacobo Arbenz. Both were seen as threats to the established order, and Arbenz' proposed land reforms were particularly upsetting to the U.S. firm United Fruit, which not only owned vast amounts of land, but also much of the country’s infrastructure.

The situation is described in great detail in, among other sources, Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala by journalists Stephen Kinzer and Stephen Schlesinger.

Guatemala as US target

Guatemala in that era became a target of the Eisenhower administration in the person of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, easily convinced by United Fruit that the reforms were a communist plot. He inspired a CIA-backed coup that overthrew the Arbenz government in 1954 and replaced it with a military dictatorship. The result? The beginnings of guerrilla warfare in Central America, 36 years of civil war in Guatemala, the disenfranchisement and eventual genocide of the Indigenous population there and the otherwise brutal savaging of the civilian population by government-aligned death squads.

Supporters of Guatemalan President-elect Bernardo Arévalo, right, face off with police outside Congress, to protest a delay in the start of the legislative session to swear in new lawmakers on Jan. 14. (AP/Santiago Billy)

Through all of it ran U.S. complicity, from military training in the United States to the constant presence of CIA operatives and military personnel.

Perhaps the darkest moments in this bleak stretch of decades came in the 1970s and1980s, when some of the most egregious human rights horrors occurred.

Then-president Gen. Lucas Garcia engaged in a vicious, individual-by-individual, intimidation of institutions by death squads. He governed from 1978, the year the Carter administration stopped military aid because of the level of human rights abuses, until 1982 when he was overthrown in a coup by Gen. Efrain Rios Montt.

President Ronald Reagan, who saw communists behind every coffee plant in Central America, was either astoundingly naïve about what was going on in Guatemala or intentionally blind to it. He assured the world that Rios Montt was "totally dedicated to democracy in Guatemala," was a victim of a "bum rap" and was "a man of great personal integrity." The Reagan administration reinstated military aid in 1983.

Despite Reagan's guarantees, the general was no democratic savior. Montt was a religious right-wing dictator who oversaw what the United Nations determined was a genocide against the Indigenous population. He was, in fact, convicted by his own national court of genocide — but died in 2018 before a final judgement could be rendered.

Sr. Rosa María Reyes poses for a photo in front of a statue of Our Lady of the Assumption after voting at a school Aug. 20 in Guatemala City. Guatemala wasn't just voting for a candidate but for change it desperately needs, she said. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Deep yearning for democracy

The war essentially exhausted itself, and peace accords were signed in 1996. But, as I've noted elsewhere, that was akin to signing legislation banning natural disasters. Official state violence simply morphed into various forms of civil violence. Guatemala became both a route for drug smugglers and a continuing source of resources to be exploited by foreign interests. Those controlling the major political and judicial institutions as well as the country's wealthy business interests — heirs of that long legacy of oppression, especially against the significant Indigenous Mayan population — resisted Arévalo's election. They even managed to delay his inauguration for nine hours.

That he ultimately was able to take office is testament to a deep yearning in Guatemalan society for democracy, a persistence that seems almost unimaginable in the face of the obstacles those forces for good had to overcome.

I once encountered the face of that persistent hope in the person of Julia Esquivel, a poet, theologian and human rights activist of international renown. It was in 2013, during the latest of a number of trips I made to Guatemala beginning in 1981. Esquivel, who died in 2019, was 82 at the time of my visit. She had been driven into exile in 1980 for eight years for opposing the government. Of our meeting I wrote that while she knew the horrors of recent Guatemalan history, she also spoke in fervent terms of her hope for the future of her country.

"There are people who have been victims of violence, who have suffered terrible violence, women who have been raped, who today are working with other women to process the rage that they feel and to recover their essential humanity," she said. "That to me is a miracle.

"The other thing that seems to be incredible when I think about it is the communities, rural communities, that continue to organize themselves and as they organize they stand up against the exploitation of the mining companies," she said, referring to clashes between mostly Indigenous communities and mining companies over land use and environmental issues. "It is amazing. How is it possible that after everything they have experienced, all that they have suffered, these communities have the strength to unite and resist? It's admirable."

Advertisement

Maybe even she would have been amazed at the degree of strength the women of Guatemala and those communities she mentioned showed in the face of recent opposition. According to journalist Mary Jo McConahay, who has reported deeply on Guatemala over decades and attended Arévalo's inauguration, the Mayan population was essential to the new president’s success.

The Indigenous authorities, she reported, "kept up a constant flow of informational meetings and communiques and organized an extraordinary 106-day peaceful siege of the Justice Ministry to pressure for respect for the vote."

Arévalo, a career diplomat with degrees in philosophy and sociology, faces great odds in his ambition to turn Guatemala into a legitimately democratic society. He campaigned on a promise to end corruption in the country, a Sisyphean undertaking.

If Guatemala has, indeed, entered a new era, it is due not only to determination but also to a host of religious witnesses who gave their lives for the causes of peace and human dignity. The Catholic role in this era has been breathtaking, including such people as the late Dianna Ortiz, an Ursuline Sister of Mount St. Joseph, Kentucky, who survived torture and rape by military forces while serving in the country. She went on to become an advocate for victims of torture.

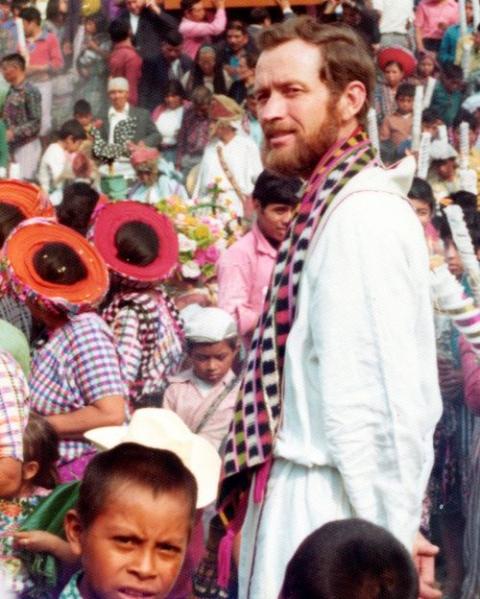

Blessed Stanley Rother was murdered in 1981 in the Guatemalan village where he ministered to the poor, was beatifified in 2017. (OSV News/CNS file, Archdiocese of Oklahoma City archives)

Fr. Stanley Rother, a priest of Oklahoma, served the Indigenous population in Santiago Atitlán from 1968 until 1981, when three masked men killed him. Rother, who had the option to return home to the U.S. after learning he was being targeted, decided to stay with the people he had pastored.

Bishop Juan Gerardi, founder of the Human Rights Office of the Archdiocese of Guatemala and a force behind the Interdiocesan Project to Recover the Historic Memory, known as REMHI, was assassinated in 1998 outside his residence. The killing occurred two days after he had publicized "Guatemala: Nunca Mas" ("Never Again"), a church-sponsored report on the three decades of violence that had torn the country apart.

A Guatemalan woman holds a poster honoring slain Auxiliary Bishop Juan Gerardi Conedera April 26, 2002, in the Guatemala City cathedral. A special exhibit marked the fourth anniversary of his murder. (CNS/Reuters)

In late April 2021, the Catholic Church in Guatemala celebrated the beatification of the 10 martyrs of Quiché, three priests and seven laymen killed between 1980 and 1991. One of the six lay catechists was 12-year-old Juan Barrera Méndez, "who helped prepare younger children for their first Communion," Catholic News Service reported. "Captured by soldiers during a prayer meeting they believed was a meeting of leftist guerillas, the boy was tortured and then shot in 1980."

The United States, supportive of the new president and the initiatives to shore up democracy as well as human rights, seems prepared to finally do something right by Guatemala.

Families enter a voting center in Chinautla, on the edge of Guatemala City, in mid-August. (Courtesy of Faith in Action)

If the civil realm in our country has finally learned something from its long complicity in the suffering of Guatemala, so should the religious realm, especially the U.S. Catholic community. The people in Guatemala we now extol as examples of civil and religious courage were not proponents of militarism, or of a version of religion that appears willing to make common cause with supporters of exploitive economics or nationalistic jingoism.

Quite the opposite.

If Arévalo accomplishes even a fraction of what the population hopes for, it will be a triumph of struggle, of determined humility, of sustained effort to rise above victimhood and to seek ways to elevate the marginalized, especially women and the Indigenous population. Some valuable lessons in all of that for the civil realm and religious leaders of its northern neighbor.