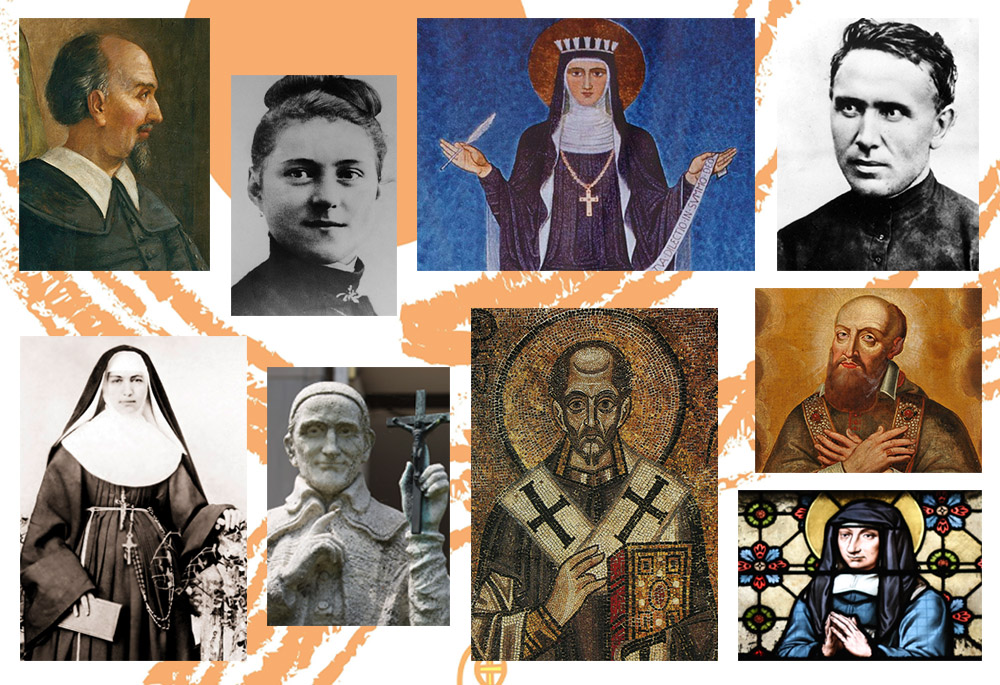

Clockwise from upper left: Bartolomé de las Casas (Wikimedia Commons/Architect of the Capitol); Thérèse of Lisieux (Wikimedia Commons); Hildegard of Bingen (CNS/Paul Haring); Damien de Veuster (CNS/Courtesy of Damien Museum); Francis de Sales (Wikimedia Commons); Louise de Marillac (Wikimedia Commons/GFreihalter); John Chrysostom (Wikimedia Commons); Vincent de Paul (CNS/Chaz Muth); Marianne Cope (CNS/Courtesy of Sisters of St. Francis of the Neumann Communities). Background: Detail of synod on synodality logo (OSV News/Courtesy of Synod of Bishops).

Pope Francis' synod on synodality envisions an inclusive dialogue that encompasses as many participants as possible. First, it is a dialogue of believers among themselves with all their varied and sometimes even inconsistent connection with the church. Synodality also invites others who are not a part of the Catholic family of faith. Ideally, the dialogue partners should include as many as possible and so represent the many rich dimensions of human experience.

Still, the synod dialogue is missing essential voices and remains incomplete. A fuller sense of who we are as God's church can widen the tent of dialogue.

The church is not only the church on earth. It is the communion of saints and the historical people of faith. In the process of synodality, we can and should be sharing our experiences and aspirations. At the same time, we must also be in dialogue with our historical tradition.

That tradition is no mere abstraction. It is embodied in the saints and all the women and men of faith who have gone before us and still walk with us. If these partners are missing, we will have flattened out our experience of church and reduced it to our current state of soul on the planet Earth.

If that happens, our dialogue will be incomplete. Even more significantly, we will have hampered the Spirit's creative movement among us.

My experience of teaching and reflecting on spirituality has led me to a strong conviction that we must be in dialogue with the saints and with our history to have a full and complete sense of ourselves and where God is drawing us forward.

Advertisement

For many years, I taught a course titled "Spirituality by Way of Autobiography." My students and I read five classic autobiographies of the tradition (Thomas Merton, Thérèse of Lisieux, Teresa of Jesus, Julian of Norwich and Augustine) to grasp across cultures, historical periods and gender experiences how the Gospel and discipleship of Jesus had its constants but also its variations.

Later, I wrote a book titled The Archaeology of Faith: A Personal Exploration of How We Come to Believe. Our faith, I affirmed in that book, is not just an individual and contemporary enterprise. It builds from a rich matrix of those who have gone before us and who continue to shape our beliefs and our spiritual life journeys.

As we draw from our history, we must always remember that it is not just the story of triumphant grace. Our collective and personal history includes sin, and that means a summons to repentance accompanied by a firm purpose of amendment. That amendment means that we do not forget where we have been, so that we can go forward in a transformed and healed direction.

In the measure that the synodal dialogue does not incorporate our history with its lights and shadows and the living communion of saints, that dialogue — however wide-ranging the number of its earth-bound and time-bound participants — will remain one-dimensional, narrow and incomplete.

This lack could also contribute to ideological divisions in a church process that ironically is meant to build unity.

Consider some of the examples of the pilgrim people of God grappling with sin and grace that both mark our past and have an imprint on our present. The sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable persons comes immediately to our minds today. Also think about the wars of religion and collusion with worldly powers to colonize, exploit and subjugate peoples.

We must be in dialogue with the saints and with our history to have a full and complete sense of ourselves and where God is drawing us forward.

There is, however, not only sin. There is also much grace embedded in our history. Consider across the years the remarkable care for the poor and infirm.

Think, too, about how we finally got some things right after years, even centuries of tragic missteps — for example, with the Second Vatican Council's declaration Nostra Aetate and our relationship with the Jewish people.

These examples, of course, do not represent abstract events. They are populated by people, and the most influential of them both then and now are holy women and men, saints both canonized and not canonized.

Think of John Chrysostom not letting the people of Constantinople forget the poor and marginalized. The same could be said of Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac as well as Damien De Veuster and Marianne Cope.

Bartolomé de las Casas stood against the tide of the exploitation of Native peoples and worked for justice. Then there is the towering medieval figure of Hildegard of Bingen, who brought together science and art.

Both Francis de Sales and Thérèse of Lisieux with their advocacy for "the devout life" and the "little way" democratized holiness, making it accessible for everyone and corrected an often-entrenched spiritual elitism.

These are just a very few examples of voices that need to be in the synod dialogues. Their concerns and their vision are entirely relevant for today's church on pilgrimage.

The question is this: How do we bring these voices from the communion of saints and sinners into the synod's tent of dialogue?

Mosaic of Sts. Barnabas and Paul above the front door of the Church of St. Panteleimon in Nicosia, Cyprus (Wikimedia Commons/Молли)

One possibility is to draw on an already existing office in the synod process. When synodal gatherings take place, there are always relatores, reporters who gather the results of dialogue and report back to the assembly. Relatores on behalf of at least some of the repentant sinners and the saints of our tradition could carry their voice into today's assemblies. They would help us to understand that we are not just the sum of our current experience but that we belong to a much larger people of faith in history who share a longed for future in the reign of God.

There is an echo of this approach in the earliest synodal assembly in the church's history, the Council of Jerusalem as we find it in Acts of the Apostles. The council was prompted by an urgent question: Do Gentiles need to be circumcised to be saved?

On their way to Jerusalem, Paul and Barnabas describe a new experience: "They reported the conversion of the Gentiles, and brought great joy to all the believers" (Acts 15:3). And they again spoke of their experience and how "God ... testified to them by giving them [the Gentiles] the Holy Spirit, just as he did to us" (15:8).

In this dialogue, someone serves as a relator and represents the past but also very much present prophetic tradition. The prophet Amos is cited to bring light to their situation: "After this I will return, and I will rebuild the dwelling of David ... so that all peoples may seek the Lord — even all the Gentiles over whom my name has been called" (15:16-17).

Today, we would do well to expand our tent of dialogue to include those who have gone before us and walk with us still. Our synodal church needs to make its pilgrim way by embracing all who belong now and from the past, on earth and in heaven above.