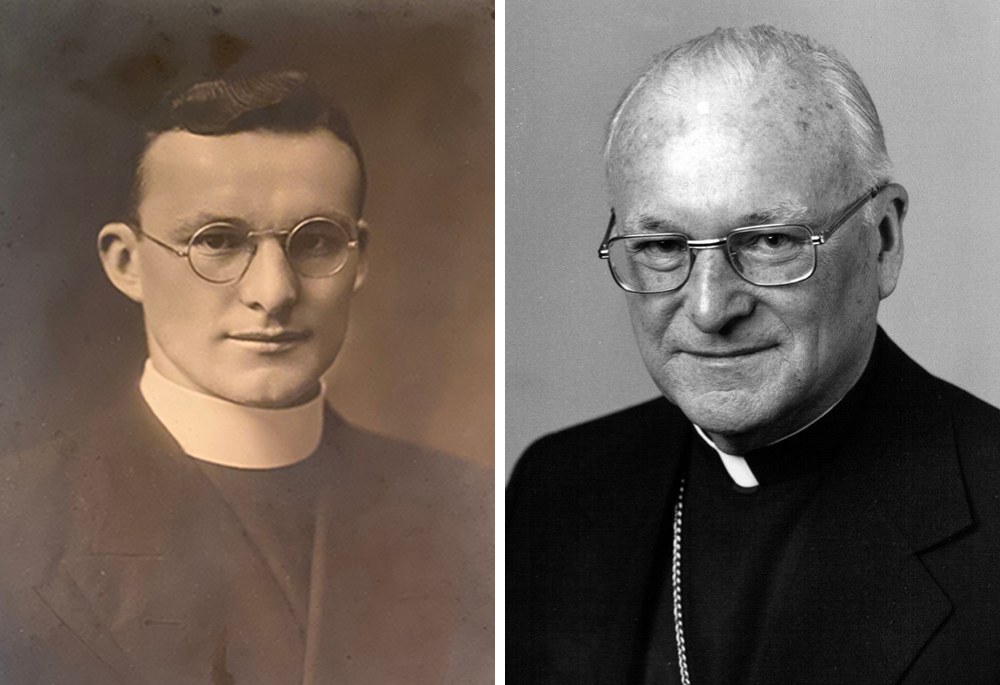

Bishop J. Carroll McCormick, left, is pictured in a portrait that he signed and gave to family members; at right, McCormick is pictured in a file photo. He headed the Diocese of Scranton, Pennsylvania, for 17 years and died Nov. 2, 1996, at age 88. (Courtesy of Stephanie Mansfield; CNS file/John Zierten)

In a 2018 grand jury report on the cover-up of child sex abuse by Catholic clergy in Pennsylvania, more than 300 priests and bishops were accused of committing or ignoring a litany of abuses, including pedophilia, sodomy, rape and sadomasochistic acts. Named in the report were three Scranton bishops, including my great uncle.

"Priests were raping little boys and girls," the report stated, "and the men of God who were responsible for them not only did nothing: they hid it all."

The cover-up was described as one of the worst scandals in church history.

"They knew exactly how it was handled," attorney Marci Hamilton, founder and CEO of child advocacy nonprofit Child USA, told me. "They thought they were not accountable to the law." (Hamilton had consulted on a similar 2005 report in Philadelphia.)

My great uncle, J. Carroll McCormick, was appointed bishop of Scranton in 1966 by Pope Paul VI. During his tenure, he was told of priests who were committing crimes against children — some as young as 10. He never notified parishioners or the police. Instead, he dismissed the allegations and transferred the offenders to other parishes where they continued to prey on minors. Many priests — when the number of new recruits was plummeting — were simply allowed to take leave for "nervous exhaustion" and sent for evaluation at church-run treatment centers like St. John Vianney outside Philadelphia.

Their priority was to avoid scandal. As one defense lawyer told me, "No money, and no new priests."

For 17 years "Uncle Carroll" protected the vilest criminals, ignoring traumatized children and keeping the information in so-called "secret archives." Canon law required bishops to keep notes on abuse allegations and he locked them away in a secret file. Only he had the key. Under canon law, those notes were to be kept for 10 years and then could be destroyed. He never destroyed them.

There are details in the report of crimes he ignored: one priest went to him and requested a leave of absence, saying he had "doubts about continuing in the active ministry." Uncle Carroll agreed. Nine years later, the priest impregnated a 17-year-old girl who gave birth to a boy. The priest was reassigned to Florida and the boy was given a scholarship to attend school by the church.

In another incident, Uncle Carroll was notified by the parents of a 10-year-old boy who was molested by a priest during a beach weekend vacation. The priest was transferred. This priest abused another boy (this time an 8-year-old) in another parish, and the church later made a $20,000 secret settlement.

And this: In 1971, a priest reported to McCormick that another priest "and a minor female were observed going into a motel room late at night on multiple occasions. They had also been seen together in public on a regular basis."

In another case, it was learned that a Scranton priest engaged in a sexual conversation with a 14-year-old girl. "Wherein he asked her about her 'sex hair' and the development of her breasts and nipples. He told her that while she was only 14 years old, she had the body of an 18-year-old," according to the report.

Advertisement

In 1980, McCormick received a letter from a parishioner who advised that the parishioners "were disgusted" with a certain priest who would not "let anyone in the rectory and that he was sleeping in sleeping bags with young boys."

After meeting with the priest accused of sexually abusing the 10-year-old boy at a beach weekend, McCormick notes: "He readily admitted the charge, insisting that once and only once did he commit an immoral act with the individual. … He stated he had never before or since become involved in that way and said he was very sorry. He claimed it was in a moment of weakness it had occurred." The priest agreed to go to St. John Vianney to see a psychiatrist.

In 2012, the Diocese of Scranton received a letter from a woman who said that in 1978 a priest in Scranton molested her when she was ten years old and engaged in grooming behavior which led to sexual abuse for a period of two years.

Some priests merely denied the accusations. A mother confronted the diocese and said a priest had molested her 16-year-old son. The priest admitted that he had "older boys visit his room in the rectory, but nothing wrong had occurred." He was told "not to do that anymore."

The same priest asked to be transferred. He was denied, being told "it would be an admission of guilt." He was then accused years later of molesting a hospital patient. One year later, staff members from the hospital said the same priest made sexual advances against a 23-year-old male patient. The priest admitted it, saying that he "did not know what comes over him." That priest was told to tell the priests who covered his Masses "he was not feeling well." In 1988, 14 years after the first accusation, the priest finally took an indefinite leave of absence.

There are lingering omissions: "In 1964, 1965 and 1966, the Diocese of Scranton received letters about Father [name redacted]'s affairs with women, his dating a young girl and getting her pregnant, and being seen in Atlantic City with this female. The letters were received from a member of the clergy, a parishioner and the mother of the girl. Nothing was found in the file reflecting an investigation or questioning of the priest."

Their cavalier attitude is reflected in one post-it note found with an email printout about a lawsuit. An unidentified person wrote: "bad abuse case. perpetrator. [Victim] sued us…we won."

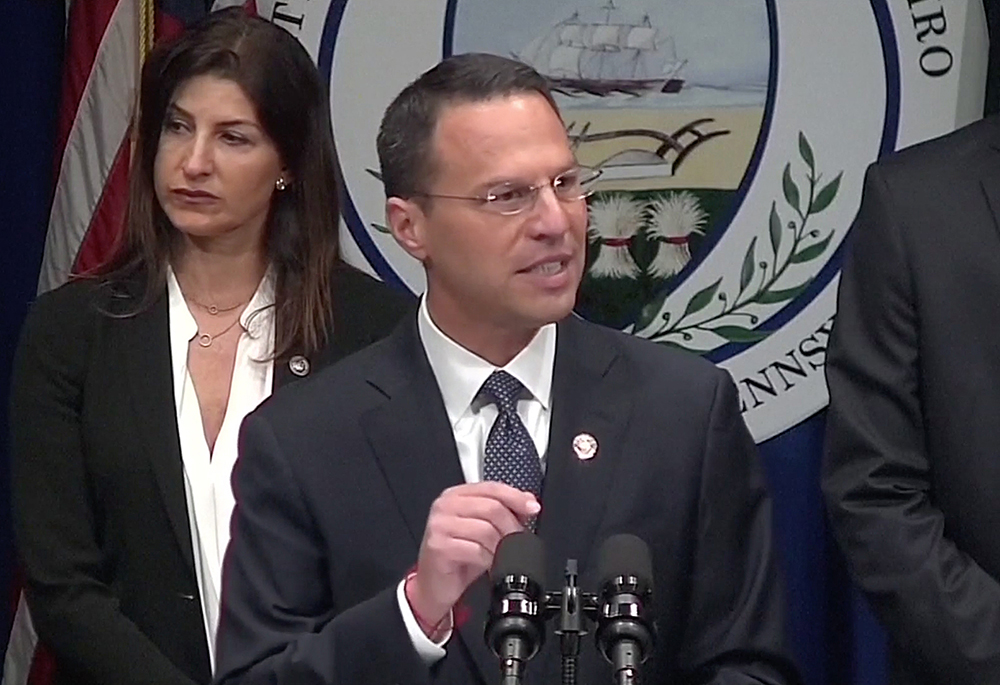

In a screen grab taken from video, then-Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro speaks during an Aug. 14, 2018, news conference to release a grand jury on a months-long investigation into abuse claims spanning a 70-year period in the Dioceses of Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, Scranton, Allentown, Greensburg and Erie. (CNS/Reuters video)

During the 24-month investigation leading up to the grand jury findings, more than 1,000 victims were identified. The real number is likely 10 times higher. The abused — both boys and girls — were given alcohol and shown pornography. They were groomed, fondled, raped, orally and vaginally. Underage girls were impregnated. They were told they were "special." Those priests my great uncle knew about went on to molest dozens of other children, many of whom were so ashamed they would not come forward for years. (The average age of child victims coming forward is about 50.)

I was probably around 4 when I became aware of Uncle Carroll. He would show up for family gatherings in his black cossack with a bright scarlet sash, large silver cross hanging from his neck, shiny shoes and a heavy gold ring on his right hand with a prominent ruby stone. We genuflected and kissed his ring. He smelled of incense.

Uncle Carroll presided over my first holy Communion, and confirmation. He gave an annual Christmas party for his dozens of nieces and nephews, the same age of many of the victims he was allowing his priests to molest. We performed for him, singing carols like "The Little Drummer Boy." He was chauffeured in a long shiny black Cadillac and always had his young male "secretary" with him. He had the bearing of a pious man — with wire-rimmed glasses and a stoic reserve.

After he participated in the Second Vatican Council from 1962 to 1965, he was vexed. He worried that he would have to give up his rings and say the Mass in English, which he refused. When he arrived at a gathering, the grownups were subdued. "Sober up — Uncle Carroll's coming." There were mild threats: if you planned to ever join a non-Catholic in matrimony, "Uncle Carroll won't marry you."

Bishop J. Carroll McCormick, center, officiated first holy Communion circa 1956 at Sacred Heart Academy in Philadelphia. Author Stephanie Mansfield is pictured third from left. (Courtesy of Stephanie Mansfield)

In Scranton, Uncle Carroll appeared to be a popular figure. He financed and built two Catholic high schools, a community center, a nursing home, and a retirement home for clergy. In his 17 years as bishop, 18 new parishes and 28 new churches were established in the diocese.

But what was the extent of his knowledge of child molestation? Was he so arrogant or blinded by obedience to protect the guilty while freeing them to commit more crimes against the most vulnerable? And to do so again. And again. Victims, many of whom as adults descended into the hell of depression, substance abuse, and in some cases, suicide.

Uncle Carroll stepped down in 1983 and died in 1996.

Once the grand jury report was made public, (the current Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro was the state's attorney general) the backlash was swift. King's College in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, announced they were removing Uncle Carroll's name from the building housing the chapel and campus ministry. The University of Scranton announced it was renaming its McCormick Hall.

Various degrees and honors were rescinded.

I didn't attend his funeral, but I read that the plumed Knights of Columbus marched, and a former governor attended. He was eulogized as a man who never sought the limelight.

Rather, "it was his stubborn and untiring determination to serve his Lord and Master."

The current bishop added: "An era has ended."