A woman holds an image of Jesus and a poster about President Donald J. Trump during the annual March for Life rally in Washington Jan. 24, 2020. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

A lot of attention has been given to the intersection of Donald J. Trump's 2024 presidential campaign and Christianity in the United States, especially certain strands of evangelical Christianity. Ironically, the unholy marriage between Trumpian political forces and an already idiosyncratic strain of Christianity is resulting in what I would characterize as a deeply secular religion. It has little to do with or resemblance to authentic Christianity apart from the use of the same appellation, recourse to sacred Scripture (albeit in often self-serving and eisegetical forms) and eerily familiar liturgical and devotional invocations and contexts.

According to several investigative reports, the Trump campaign has been working with organizations intent on infusing overt Christian imagery and language into Trump's political platform, with hopes of exciting his prospective Christian base. In January, a viral video titled "God made Trump," which was aimed at Iowa caucus goers, was published by an independent group and quickly adopted by the Trump campaign.

Even though many Christian ministers around Iowa objected to the implications of the video — that God has ordained Trump to be a "caretaker" for the United States or that Trump is otherwise divinely chosen — those self-identified Christians most supportive of Trump and this kind of rhetoric are actually non-church-going Christians. Thus, the concerns raised by ordained Christian ministers were not reaching the most passionate Trump supporters.

To be clear, this is a real religion that we are talking about here; it's just not Christianity.

A recent Politico report highlighted the key role a Washington, D.C., conservative think tank is playing in "developing plans to infuse Christian nationalist ideas in his administration should the former president return to power."

According to that report, Russell Vought, president of the Center for Renewing America, and his staff have explicitly embraced the term "Christian nationalism" and marked it as a priority for a potential second-term Trump administration.

The article explains, "Christian nationalists in America believe that the country was founded as a Christian nation and that Christian values should be prioritized throughout government and public life. As the country has become less religious and more diverse, Vought has embraced the idea that Christians are under assault and has spoken of policies he might pursue in response."

In recent weeks Trump's blatant, if often awkward, attempts to lure Christians (at least of a certain ilk) to his campaign took an even more bizarre turn.

As has been widely reported, on March 26, just days before Easter, Trump posted a video on social media in which he encouraged his supporters to purchase the "God Bless the USA Bible." This edition contains not only the canonical books of scripture in the King James Version translation, but also an assortment of non-Christian texts like the U.S. Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the Pledge of Allegiance and the chorus of musician Lee Greenwood's song "God Bless the USA."

In a repeatedly lampooned excerpt from the promotional video, Trump says, "All Americans need a Bible in their home, and I have many. It's my favorite book."

But what I found more interesting, and less humorous, was another line in his video: "Religion and Christianity are the biggest things missing from this country." While many of his supporters have convinced themselves that Christianity may be missing from or under attack in this country, what Trump has been offering them in return is not a vision of authentic Christianity, but a different religion called by the same name.

A couple of years ago I mentioned in my column an essay by the renowned Christian ethicist Stanley Hauerwas, who wrote about what he calls "America's God." In light of the Trump campaign's effort to recast Christianity as something accommodating nationalistic, anti-immigration, anti-LGBTQ and other discriminatory and harmful views, I have been thinking again about Hauerwas' insights.

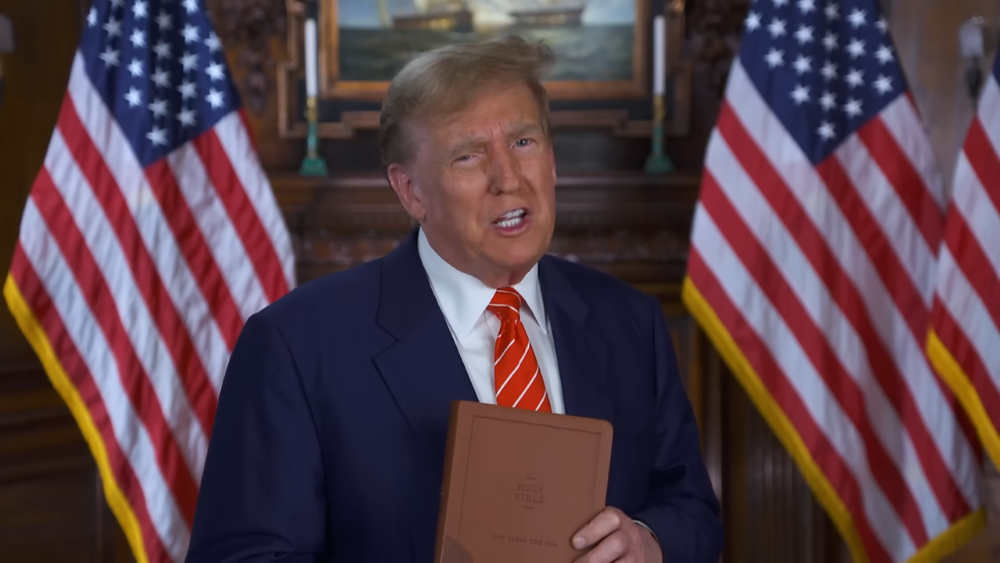

Former President Donald J. Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, is pictured in a video pitching sales of his $60 "God Bless the USA Bible" during Holy Week, in partnership with country singer Lee Greenwood. (NCR screenshot/YouTube/Lee Greenwood)

In his article, published in 2007, Hauerwas writes: "Ironically, the feverish fervency of the Religious Right in America to sustain faith as a necessary condition for supporting democracy cannot help but ensure that the faith sustained is not the Christian faith."

He notes that Americans are statistically more likely to go to church or some other worship service than their European counterparts. But the messages they hear in preaching and religious formation do little to challenge secular and political presumptions that inform and shape their outlooks, or their personal and communal lives.

What Hauerwas calls "America's God" is shorthand for what I would simply call an idol. Belief in such a "god" is not belief in the God of Jesus Christ as informed by the Gospels and tradition, but the divinization of a self-serving projection of ideas, positions and campaign platforms.

It's striking that 17 years ago Hauerwas was able to say, "I cannot avoid the reality that American Christianity has been less than it should have been just to the extent that the church has failed to distinguish America's god from the God we worship as Christians."

Nearly two decades later, this statement is both more true and more disturbing. This is especially because while the idol of America's god has been around for some time, Trump now seems to be forming another kind of religion that worships such an idol, and the number of his faithful adherents is not insignificant.

The New York Times this week published a substantive article by political reporter Michael Bender that describes exactly what the Church of Trump looks like. Longstanding hallmarks of Trump rallies have included his firebrand diatribes and confusing word salad meanderings, often with energy and bombast. Recently he has taken to ending his events with something eerily resembling a religious worship service.

Bender describes this recent shift: "Soft, reflective music fills the venue as a hush falls over the crowd. Mr. Trump's tone turns reverent and somber, prompting some supporters to bow their heads or close their eyes. Others raise open palms in the air or murmur as if in prayer." He adds, "The meditative ritual might appear incongruent with the raucous epicenter of the nation's conservative movement, but Mr. Trump's political creed stands as one of the starkest examples of his effort to transform the Republican Party into a kind of Church of Trump."

Despite the use of language that at first appears to be "Christian," the religion that Trump is promoting and that many of his followers are adopting is merely a simulacrum of authentic Christianity. This pseudo-Christianity bears a superficial resemblance to the real deal, but lacks the moral exhortations, scriptural foundations or doctrinal grounding.

Advertisement

To be clear, this is a real religion that we are talking about here; it's just not Christianity. It has doctrinal propositions ("America is a Christian nation," "God made Trump," "America First," etc.); it has supreme religious authority (His Holiness Donald Trump); it has religious imagery and symbols ("MAGA," depictions of Trump and Jesus as equals or partners, and so on); and it has liturgies (Trump rallies are its most solemn worship and online communities are its ongoing fellowship).

On this last point about the liturgical valence of Trump's rallies and religion, it is worth reading the philosopher James K. A. Smith's 2009 book Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation, which studies the nature and reality of secular liturgies and appears stunningly prescient given the rise of Trump.

For Trump, this pseudo-Christianity that worships the "America's god" of his creation serves as a vehicle to attract and retain his faithful adherents with hopes that they will deliver him the reelection he wants at any cost. For his followers, this Trumpian religion provides them with something resembling a mirror into which they can gaze and see reflected back to them a "Christianity" that aligns comfortably with whatever it is they desire. Together, this combination portends danger for both politics and religion, which should concern anybody who is serious about authentic Christianity.