Religious artwork and vintage photographs adorn a wall behind a voter as he completes his ballot at a polling place inside St. Leo the Great Roman Catholic Church, Nov. 6, 2018, in Baltimore. (AP photo/Patrick Semansky)

In America's religious landscape, the groups attracting the most public attention are those staking out the poles in our political divides: the shrinking, aging but still influential group of white evangelical Christians on the right vs. Black Protestants and the growing religiously unaffiliated cohort on the left. With the media, political and philanthropic spotlights all focused on the edges, however, America's important religious middle remains in the shadows.

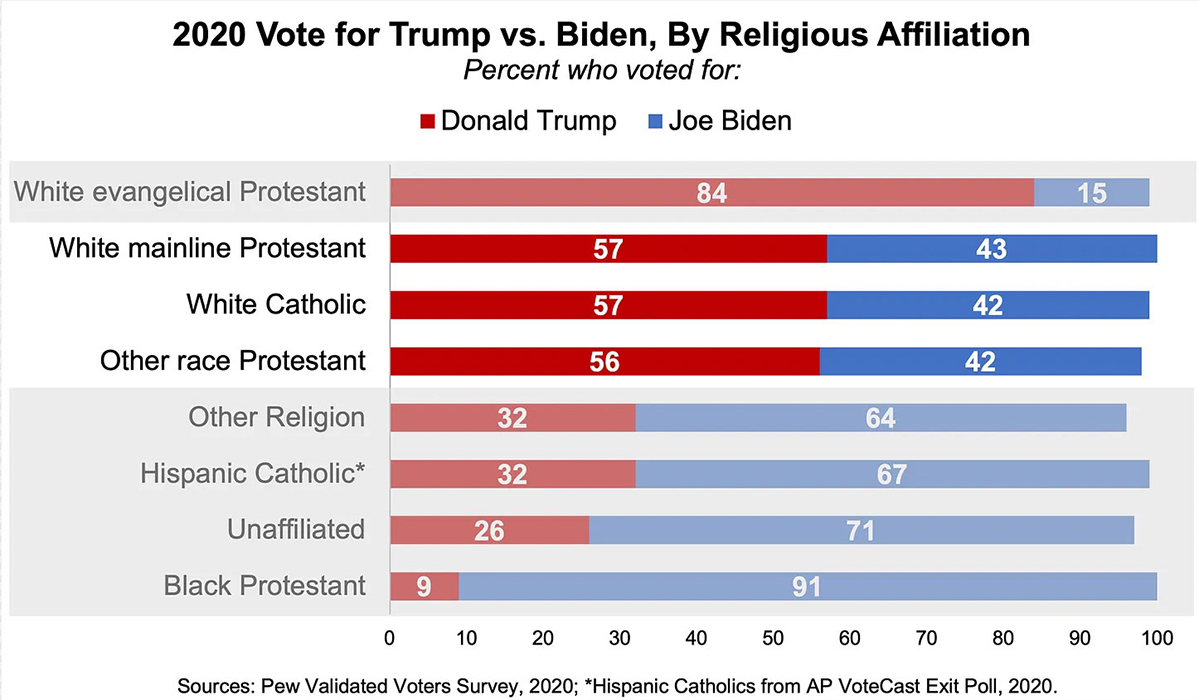

To be sure, the religious groups at the poles powerfully demonstrate the eye-popping levels of political polarization in the country. In the 2020 election, according to the 2020 Pew Validated Voter Study and the 2020 AP Votecast Exit Poll, 84% of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, while 71% of religiously unaffiliated voters and 91% of Black Protestants voted for Joe Biden.

You can also see the political chasms in the religious landscape on hot-button issues such as abortion and immigration: Three-quarters (75%) of white evangelical Protestants say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases; by contrast, 70% of Black Protestants and 82% of religiously unaffiliated Americans believe it should be legal in all or most cases.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of white evangelicals, compared to only about one-quarter of Black Protestants (25%) and religiously unaffiliated Americans (23%), favor extreme measures at the U.S. border, such as "installing deterrents such as walls, floating barriers in rivers, and razor wire to prevent immigrants from entering the country illegally, even if they endanger or kill some people," according to PRRI's 2023 American Values Survey.

These divides are troubling, and important for understanding the challenges our democracy is facing. But they are not the entire story.

On the right, after steep declines over the last two decades, white evangelical Protestants comprise only 14% of today's U.S. population and 19% of 2020 voters. On the left, Black Protestants have been holding steady at 8% of both the population and voters, while the growing group of religiously unaffiliated Americans has ballooned to 27% of the population and 25% of voters. These groups anchoring the right and the left, combined, account for only about half the country.

Breakdown of Trump and Biden 2020 election voters by religious affiliation (RNS/Graph courtesy of Robert P. Jones)

Among the groups comprising the remainder of the religious landscape, the divides are less lopsided. In this neglected religious middle, three groups' partisan and ideological divides are the most balanced: white mainline/nonevangelical Protestants (14% of the population and 15% of 2020 voters), white Catholics (13% of the population and 14% of voters), and "Other race Protestants" (6% of the population and 4% of voters). These groups all lean Republican, but not overwhelmingly so; they each supported Trump over Biden in 2020 by slightly less than a 60-40% margin.

Across a number of measures, you can see ways in which these groups look significantly different from the white evangelical Protestants. They don't fit comfortably into left-right stereotypes. (Note: In the analysis below, I cite data for Hispanic Protestants, who represent the largest subgroup in the composite "Other race Protestant" category.)

Trump and the 'big lie'

While just under 6 in 10 of each group supported Trump in 2020, majorities of each nonetheless reject the idea that the election was stolen (59% of white mainline Protestants, 59% of white Catholics, and 56% of Hispanic Protestants). By contrast 60% of white evangelicals believe the "big lie" that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump.

Political ideology

While a plurality of both white mainline Protestants and white Catholics identify as conservative, more than one-third identify as moderate and about 1 in 5 identify as liberal. Among Hispanic Protestants, equal numbers identify as conservative or moderate (about 4 in 10 each), and 1 in 5 identify as liberal. Among white evangelical Protestants, 7 in 10 identify as conservative.

Abortion

Nearly-two thirds (65%) of white mainline Protestants and 59% of white Catholics say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Hispanic Protestants are more divided (46% legal vs. 53% illegal in all or most cases) but look significantly different than white evangelical Protestants, among whom only 24% believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

Same-sex marriage

Approximately three-quarters of white mainline Protestants (77%) and white Catholics (73%) favor allowing same-sex couples to marry legally. Hispanic Protestants are divided (50% favor vs. 48% oppose) but considerably more supportive than white evangelicals (36% favor).

Immigration

Majorities of white mainline Protestants (56%) and white Catholics (55%) believe the growing number of newcomers from other countries threatens traditional American customs and values, compared to only 32% of Hispanic Protestants. At the same time, about 6 in 10 white mainline Protestants (59%) and white Catholics (58%), along with two-thirds of Hispanic Protestants (66%), favor a policy that would provide a path to citizenship for immigrants living in the U.S. illegally. On both of these measures, there is significant daylight between these groups in the religious middle and white evangelical Protestants, among whom 7 in 10 say newcomers threaten American culture and only 45% support a path to citizenship.

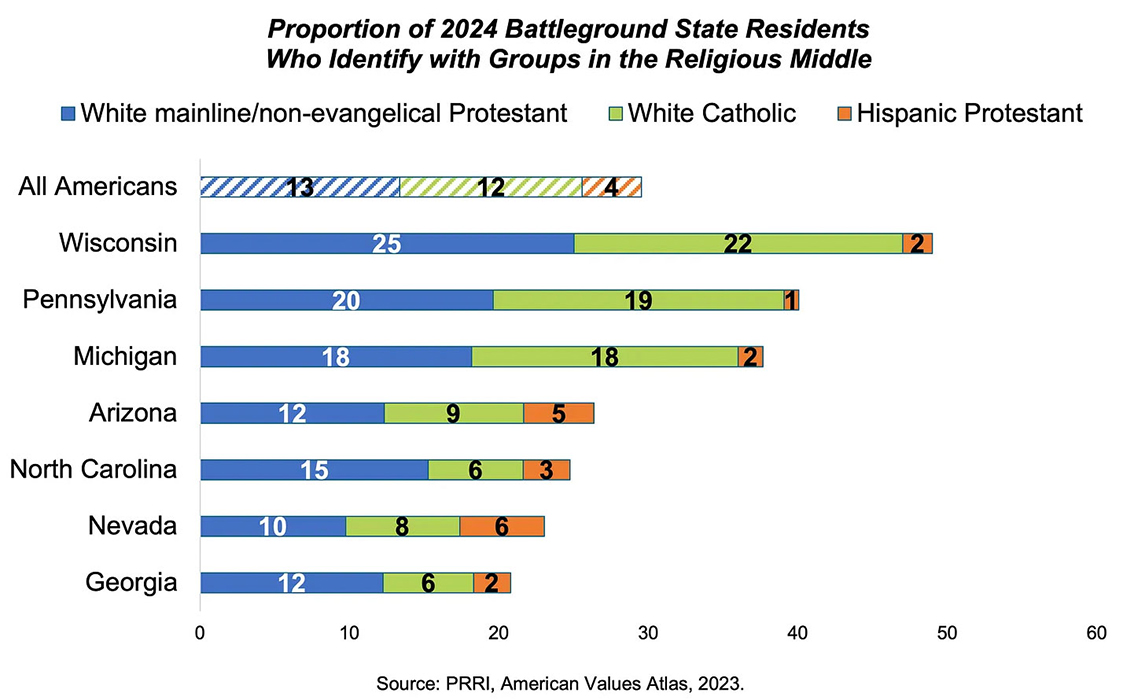

These groups in the overlooked religious middle are also poised to play an outsized role in determining the outcome of the 2024 presidential contest. In the Rust Belt battleground states, they comprise about 4 in 10 or more of the state's residents. In Wisconsin, they represent nearly half the population.

Advertisement

Across the Sun Belt battleground states, the religious middle is smaller but nonetheless comprises one-fifth to one-quarter of the population. While Hispanic Protestants remain a small proportion of Rust Belt states, they comprise 5% of Arizona residents and 6% of Nevada residents — enough to make a difference in a tight election. (In 2020, Biden won Arizona by 10,457 votes and won Nevada by 33,596 votes.)

Notably, in all the battleground states except Georgia and North Carolina, white mainline Protestants alone outnumber white evangelical Protestants.

Historically, dramatically more resources have been marshaled to understand, engage and mobilize the groups on the ideological poles of the religious landscape. In tight elections, like the 2024 presidential race, base turnout always takes precedence in campaign strategy. But if the campaigns are looking for ways to move the needle, outreach to these religious middle groups will almost certainly yield a higher return on investment than to more locked down groups like white evangelical Protestants.

Proportion of battleground state residents identifying in the religious middle (RNS/Graph courtesy of Robert P. Jones)

Cleavages within the groups in America's religious middle are plainly visible.

Many white mainline Protestant denominations, for instance — most recently the United Methodist Church — have been roiled by debates over the morality of same-sex relationships and over their historical complicity with white supremacy. Their churches house a challenging clergy-laity gap, with clergy generally more liberal than their congregants.

White Catholics are largely supportive of abortion rights and marriage rights for LGBTQ people, in direct contradiction to church teaching. They are also experiencing tensions between the more progressive leadership of Pope Francis and the more conservative bent of the U.S. Catholic bishops.

Hispanic Protestants, a small but growing and increasingly complex group, are more conservative on cultural issues. But their ties to recent immigrants to the U.S. inoculate them against the worst of Trump's xenophobic appeals even as their theological ties to white evangelicals provide inroads for some of MAGA's apocalyptic and authoritarian appeals. On the other hand, they prioritize economic issues such as health care, education and rising costs of everyday items above culture war issues.

But in our era of polarization, the disagreements among America's religious middle should be seen as a virtue. Amid the hyperpolarization plaguing our nation, we should be looking diligently for institutions that hold us together, not just in comfortable agreement but in good-faith debates.

If we take the long view, with our eyes fixed on the goal of a healthy democracy, we'll refocus our attention toward these groups in the neglected religious middle, where denominations and pastors and churches are struggling, however imperfectly, to hold people in community across partisan and ideological lines.

(This article first appeared on Robert P. Jones' Substack newsletter. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)