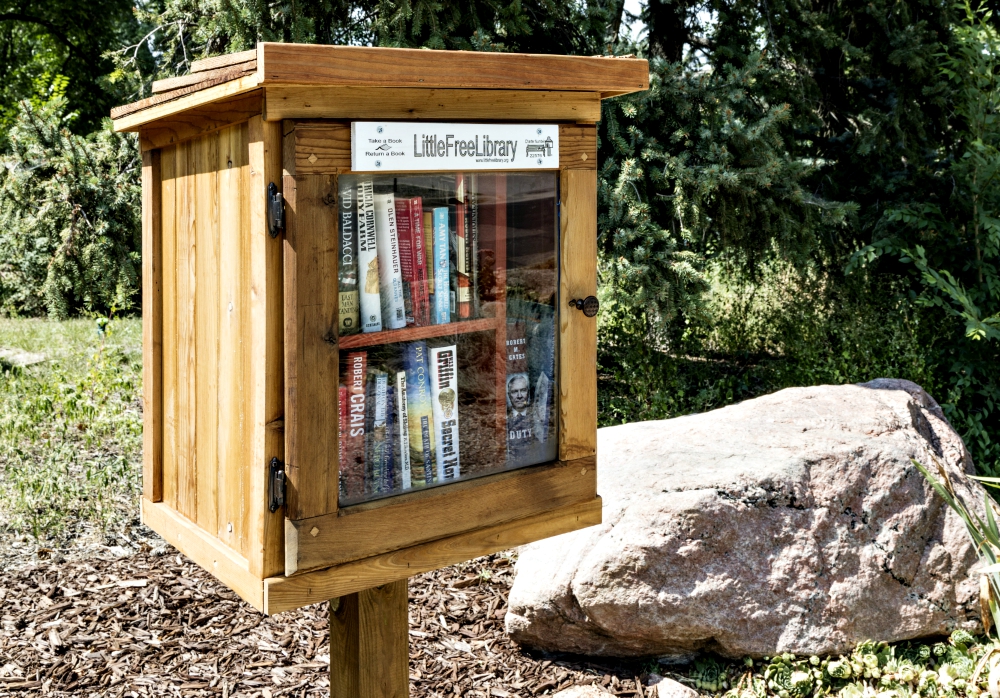

A Little Free Library is seen in Colorado Springs, Colorado. (Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress/Carol M. Highsmith)

My youngest child never opened a Facebook account back when his peers were all invested in that particular platform. His friends couldn't understand it. He told them, "Let's not be Facebook friends. Let's be friends."

His words have stayed with me as I observe the deepening damage done by online rants and rages, screen-shrouded anonymity loosening those norms of courtesy and restraint that make our life together possible. When virtual community is all that we have, then we are stranded, castaways — alone, but without solitude, alone, but without stillness. Just alone. It is a terrible fate, and we must struggle against it.

Last Christmas, in 2016, my children gave me a modest tool for building real community. They gave me a small wooden box on a pole that my son-in-law cemented in front of our house, just west of the driveway's footprints and handprints of grandchildren sunk in the concrete, and just north of the Peking cotoneaster hedge. They gave me a Little Free Library.

Little Free Library is a modest project that has captured the imaginations of thousands of us all across the country. The library boxes look like tiny houses on sticks. Mine is barn-red with a metal roof, though others paint them in all colors and decorate them with images of flowers and birds.

Each box has a door with a clear Plexiglas insert and a latch. At the top of the door, there is a wooden plaque with the owner's charter number. My charter number marks me as a member of the Little Free Library community. We are a far-flung group, but the work we do, and the pleasure we have, is all local. It is a face-to-face, hand-to-hand, book-to-book movement. The movement's motto: "We all do better when we all read better."

Advertisement

Inside the box are the books, two shelves of them. There is no particular order and certainly no Dewey Decimal System or checkout procedure. There are just the books I have read (or meant to have read) and do not wish to keep, as well as the books my neighbors bring and shelve there.

I'm not sure my library satisfies the charge to "read better." It is usually stuffed with self-help books and mysteries and the occasional romance. John Grisham and Stephen King and Ken Follett and Michael Connelly and Mary Higgins Clark seem to have found a permanent home within. Different books, same authors, though Lee Child's Jack Reacher stories are always gone within a day.

Just about every "Idiot's/Dummies' Guide to [name your poison]" has settled there. All the numerical steps and habits of highly (fill-in-the-blank) people show up. Religious texts of the "everyone-but-me-is-wrong-and-I'll-tell-you-why" variety make an occasional appearance.

Out of that jumble, I've only removed two volumes for cause. One was Fatherhood by Bill Cosby, which seemed both too soon and too sad for my little library, and a book on various erotic pleasures, which looked distinctly out of place (in all senses of that phrase) next to a paperback copy of The Secret of the Old Clock. I read and savored this first Nancy Drew mystery when I was a gir,l and I can tell you (without giving away the ending) that the old clock's secret is G-rated. Nancy's father, Carson Drew, respected criminal attorney, would surely have approved my decision.

So I might amend the Little Free Library slogan from, "We all do better when we all read better," to, "We all do better when we all meet one another and talk together better." I can look out my kitchen windows and watch folks browsing through the titles. It is a short walk from the kitchen to the driveway to introduce myself and to encourage a browser to become an owner. (Some libraries have a "take a book, return a book" policy, but we are in danger of being buried in a book and magazine and newspaper tsunami here, so I encourage a "take a book and keep a book" policy.)

I've met neighbors as I was pulling out of or into my driveway while they were reading the book jackets and blurbs. I've gotten to know a checker at my local grocery store, who, though he lives several miles away, likes to walk down my street on his way to the park and who always stops and takes a look at what's new.

I've met an elderly man who pushes a grocery cart up and down the block and who can be counted on to stuff three or four volumes at a time into his knapsack. If I read an online posting about the homeless or the mentally ill in town, I can feel my anxiety levels rising. But meet the shopping cart man in person, and the impression is one of eccentricity rather than menace.

Our area is sprouting Little Free Library boxes on block after block. One of the happy effects of all this happened this Christmas when my neighbor hosted, not a cookie exchange, but a book exchange. We each brought a book and each left with a book. I came away with a thick volume of mystery stories, just right for a cold winter's night. And I will, no doubt, be wedging it in the Little Free Library shelf come spring.

So, stop on by. You might just find your next good read, and you might meet some people as entertaining as any book.

[Melissa Musick Nussbaum's latest book, with co-author Anna Keating, is The Catholic Catalogue: A Field Guide to the Daily Acts That Make Up a Catholic Life.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time this column, My Table Is Spread, is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert signup.