A screenshot shows George Weigel's recently published essay at National Catholic Register, in which he calls for a "repurposing" of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. (NCR screenshot)

George Weigel, keeper of the flame for St. Pope John Paul II, was once an exemplar of a neoconservative approach to religion and politics that many of us thought was misguided or wrong, but which at least engaged in serious discussion about serious issues. Neocons do not drive the debate any longer, and so reading Weigel the past few years has become optional.

However, Weigel's recently published call for a "repurposing" of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development (CCHD) is so tendentious it requires a response.

Weigel begins by mischaracterizing the Great Society. "The American bishops created CCHD in 1969 as a kind of Catholic analog to Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society programs," he writes. "At the time, many well-intentioned people believed that the increasingly severe problems of America's inner cities could be solved by large infusions of federal cash."

The Great Society programs were designed to expand the social welfare state in the face of human need. The two foremost programs, Medicare and Medicaid, were developed to help the elderly and poor cope with the rising cost of health care. Scientists and doctors were devising treatments that had not been possible before, but the treatments were expensive. Would Weigel have preferred that we not make bypass surgeries available to those with clogged arteries? Or that we limit improvements in maternal health to those able to afford private health insurance? Long-term care, which is enormously expensive, was once provided by the extended family, but families no longer live in the same place century after century. What is Weigel's solution?

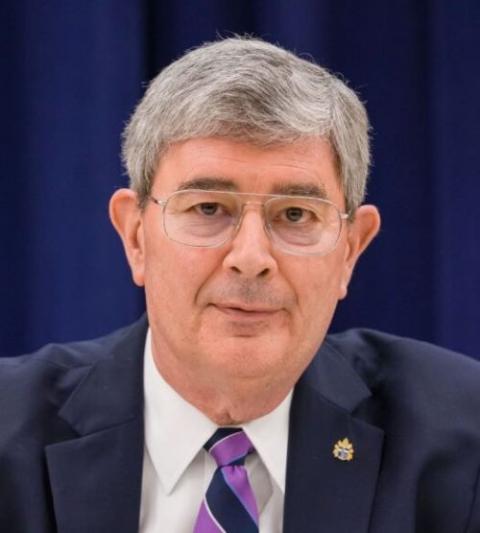

George Weigel (Ethics & Public Policy Center)

He has none. He invokes the famous 1965 Moynihan report to slam the Great Society programs. "Billions of dollars of federal money did not solve the problems of impoverished urban communities, however, because of factors already identified in the 1965 Moynihan Report, which located many of the sources of urban deterioration in the breakdown of marriage and family structures — a cultural crisis not amenable to solution by cash," he writes. But Moynihan himself did not oppose the Great Society programs. And he recognized the cultural complexities of the breakdown in marriage, especially for Black Americans. Weigel ignores all of this.

Instead, he lumps together yet more complicated history to coarsely attack the CCHD's model of community organizing. "And as Great Society programs evolved," he continues, " 'community organizing' often led to radical politics, the catastrophic effects of which are now visible in cities like Chicago, home of 'community organizing' as defined by the movement's guru, Saul Alinsky, in his books Reveille for Radicals and Rules for Radicals." This kind of monocausal analysis is unworthy of serious engagement. Chicago — and other cities — have their problems, and their hopes, but neither the problems nor the hopes are simply the result of community organizing or radical politics.

Certainly, the Great Society programs, like most human endeavors, had unintended consequences. For example, the 1968 Fair Housing Act began the slow, still unfinished work of confronting discrimination in housing, helping many Black and Hispanic Americans move into the suburbs, purchase real estate and build equity. This had the unintended effect of diminishing social capital in the inner-city neighborhoods at precisely the time blue collar jobs were being shipped elsewhere. Americans can and should discuss ways to address such unintended consequences, while also celebrating the successes the programs achieved. Weigel reduces it all to a caricature of government spending.

In his heyday, (George) Weigel was a writer who engaged ideas substantively, and with whom one could have serious disagreements. Now he traffics in ideological reductionisms and gross caricatures.

The simplistic, monocausal analysis continues. "Insofar as CCHD funds have supported community organizers whose chief accomplishment has been to radicalize the Democratic Party to the point where the once-traditional home of American Catholics has become a poisonous environment for Catholics who take seriously Catholic teaching on life issues and related matters, CCHD has paid, if indirectly, for anti-Catholic political activity," he writes. I agree that the Democratic Party has become "poisonous" for Catholics who take certain life issues seriously. For other life issues like climate change, the poison comes from the GOP. But, in both cases, the reasons for these changes are many and various. Weigel distorts and inflates the role community organizing played in partisan shifts by ignoring other factors.

Weigel turns to — who else? — Pope John Paul II for a solution but then proceeds to distort the pope's teaching. "As proposed by Pope St. John Paul II in his epic 1991 social encyclical Centesimus Annus, the Catholic approach to anti-poverty work begins with an affirmation of the potential latent in the poor, and then seeks to unleash that potential through empowerment programs that inculcate and develop the virtues and skills necessary to participate in the networks where wealth is created and exchanged today." Empowerment is not a bad definition of the goal of community organizing, but for Weigel, the focus is always on individuals cultivating their own virtue and never on the role of the community and its capacity to help, or hinder, the overcoming of poverty. We need both.

Advertisement

Finally, Weigel repeats a proposal first floated by Springfield, Illinois, Bishop Thomas Paprocki to redirect CCHD money into Catholic parochial education because Catholic schools are the best anti-poverty program going. I agree that Catholic schools play a vital role in helping tens of thousands of children escape poverty. They also provide social capital to the neighborhoods they serve, as University of Notre Dame professors Nicole Garnett and Margaret Brinig demonstrated a decade ago in their book Lost Classroom, Lost Community: Catholics Schools' Importance in Urban America. It would be worthwhile examining how CCHD programs could collaborate with our Catholic schools. Pitting them against each other serves no useful purpose.

In his heyday, Weigel was a writer who engaged ideas substantively, and with whom one could have serious disagreements. Now he traffics in ideological reductionisms and gross caricatures. It is sad.