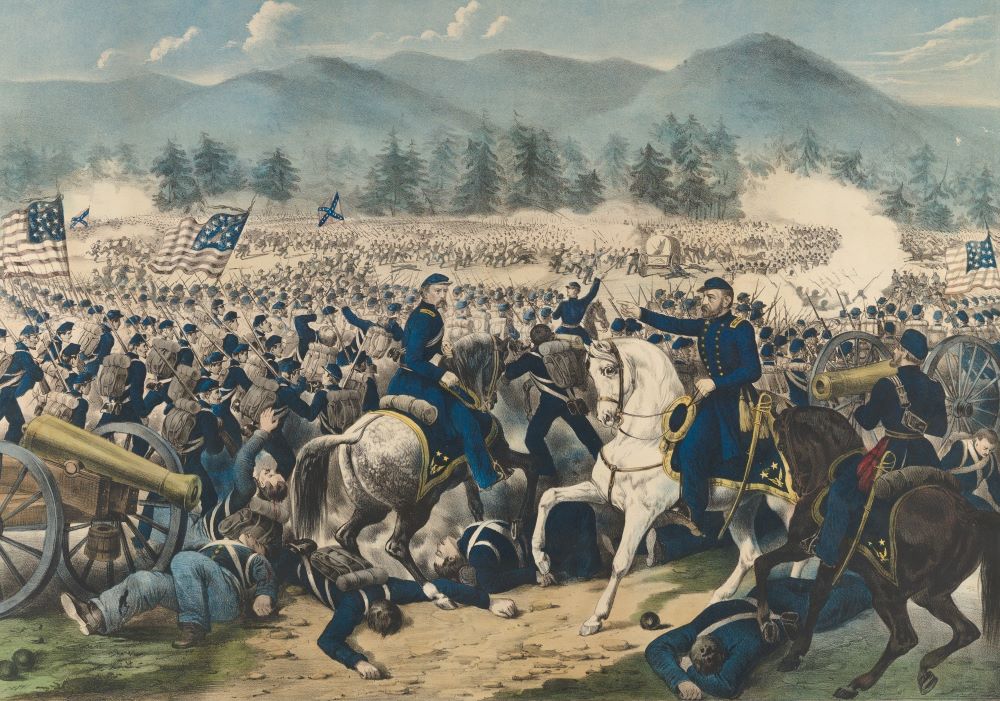

"The Battle of Gettysburg, Pa., July 3rd, 1863," a lithograph by Currier & Ives (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When James Davison Hunter publishes a book, people need to pay attention. Hunter's 1991 book Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America delivered the most useful — and often used — metaphor for the political changes of the late 20th and early 21st century. His new book, Democracy and Solidarity: On the Cultural Roots of America's Political Crisis, does the same for the present time, pointing to the most basic question our country must face and answer: Can our democracy survive when the cultural wellsprings of social solidarity run dry and no longer generate a shared mythos that unites Americans?

Hunter starts with a rich and nuanced historical survey, and today I will focus on that part of the book. On Monday, we'll wrap up with a look at how Hunter analyzes the current moment.

The historical survey Hunter undertakes comes with a sharp historiographical lens, one that he states clearly. "While it is true that politics is mainly about the use and administration of power, for it to be about more than power — for example, about justice or freedom or equality — it depends upon a realm that is relatively independent of politics," he writes. "That is why, in the end, culture is prior to politics." He argues that "Every culture implicitly poses and addresses (in various ways) these proto-philosophical questions — the questions of metaphysics, epistemology, anthropology, ethics, and teleology." And, so, Hunter swims against some powerful academic tides which only analyze power or, at best, consider ethics apart from anthropology or metaphysics.

It is this deep level of cultural analysis that makes this book so easy to engage for Catholics who know that reducing politics or religion to ethics is the first step toward misunderstanding.

One other critical point that Hunter mentions up front, and repeats several times throughout the book: These deep cultural sources he is examining are strongest when they are implicit, when they are so widely and deeply held that they do not need to be mentioned. This is why so many attempts by non-historians to undertake history fail: They do not recognize what was unsaid in their speeches and unwritten in their correspondence, what was in the air people breathe.

Turning to the founding, then, Hunter argues that the "the strata of social thought that underwrote liberal democracy took shape as a hybrid-Enlightenment, a blending of cultural sources that drew from many different tributaries of thoughts and practice." The hybrid had to be opaque enough for people who understood concepts like "freedom" and "equality" very differently from one another to forge an "affirmative solidarity" which grounds "common understanding and common affections." It was not enough then — and it is not enough now! — to have a negative solidarity, "a coming together born in reaction to the presence of an enemy or, perhaps, in response to a crisis."

The hybrid-Enlightenment was no mere softening of the rough edges of Voltaire with the rough edges of Calvin. Hunter observes, "the Enlightenment in America carried a Calvinist moral sensibility, even when it repudiated its doctrines of original sin, the divinity of Christ, the Trinity, the existence of miracles, and the like. The reason was that everyday personal and social ethics were essentially the same." The syncretism of the founding era was thorough-going but uneven, with room for deists and orthodox Christians. What it forged was new ideas about citizenship, in which "ordinary men had the agency to determine the frameworks of public life." This caused endless political disputes because people meant different things by ideas like liberty and equality, but these ideas had a power of their own, power enough to bind early Americans into a sense of common purpose.

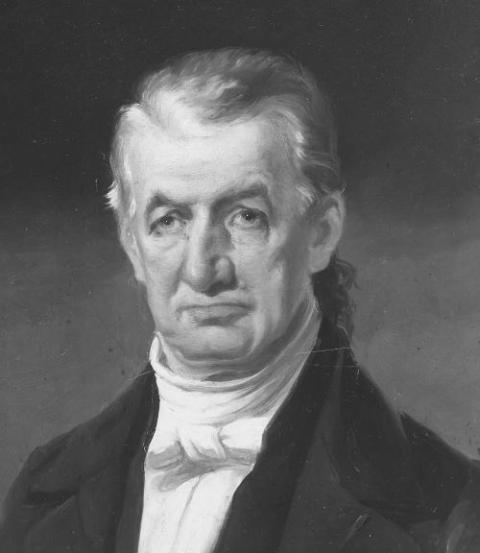

A circa 1840 painting of Lyman Beecher (Wikimedia Commons/Museum of Fine Arts Boston)

In the first half of the 19th century, the democratizing force of the Second Great Awakening had a profound effect on national self-understanding, and "revivalist evangelicalism came to dominate the cultural logics of public life in this period." Hunter looks closely at Lyman Beecher, who epitomized the interpenetration of religious and political ideas in the antebellum era, forging a narrative in which America was a new Israel, and from which all the various efforts at social reform, including abolitionism, sprung. It was in this period that America was not just a nation of Christians; it was a Christian Republic, and self-consciously so.

I asked Hunter about how the millennial understanding of America's destiny he catalogs in that antebellum era relates to concerns today about an often fuzzily defined Christian nationalism.

"I think we are seeing a couple of things," he told me. "One is that for the better part of American history, certainly from the founding especially in the first two-thirds of the 19th century, but continuing on into the middle of the 20th century, Christianity, in all of its complexity, occupied the center in elite institutions of culture formation." In short, sloganeering about "Christian nationalism," either in favor or opposed, misunderstands much of American history.

Hunter focuses on the many ways that Americans struggled with each other over their shared national mythos, and the many ways the country as a whole fell short of its stated ideals. He examines the "boundary work" of national identity at each stage of the story, how enslaved Black Americans, Native Americans, Catholics and Mormons were all kept in the category of "other," until they weren't, and how institutions like the Black church and movements like abolitionism all sprang from the shared, democratized Christian heritage to which slaveholders in the South also subscribed. As he said, the national mythos has to be opaque!

The Civil War remains the moment in American history when the country failed to "work through" the tensions in its national mythos. The anthropological conflict in seeking to answer the question "Who is a person?" could not be resolved. The differences were categorical. "The inability to resolve these contradictions in nation life either rationally, constitutionally or theologically meant that they could be resolved coercively, through military strategy and might," Hunter writes.

Abraham Lincoln delivers his second inaugural address as president of the United States on March 4, 1866, in Washington, D.C. (Wikimedia Commons/Alexander Gardner)

Toward the end of that war, Abraham Lincoln delivered his Second Inaugural Address. Hunter echoes Alfred Kazin's observation that the speech was the culmination of the age of belief. Then he makes a claim I found confusing: "By taking sides so prominently in the war and having intensified the moral stakes of the conflict, biblical faith, in effect, had discredited itself as a source for interpreting and directing policy matters and directly influencing public life." I would have thought the Union side would have felt vindicated by the result of the battle. Hunter argues that religion's loss of authority in public life began to unwind at that moment.

I asked Hunter about this claim that religion began to lose its cultural authority at the end of the Civil War.

"I don't think they were aware of it at all," he told me. "I do think that the catastrophe of the Civil War was not just in the death count, it was in the number of wounded which was far more, and given the nature of health care at that time, it just destroyed, certainly the southern economy, but it was just this — the nation was just hit by a truck."

"There was quick work done, with the Emancipation Proclamation and with the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, to right the ship, create national unity, but at an emotional level, a social level, this was a body blow that was deeply intimate and it pervaded every aspect of the social order. So, bouncing back from that, generated a lot of doubt," he added. "And, of course, this is the time when Darwin is publishing, we are seeing the growing Enlightenment sensibility and the promise of a kind of secular science, the Berlin model of a German university was not long after being embraced by Johns Hopkins and other major universities. I think a number of things came together, but not least, a kind of emotional fallout [after the Civil War] at a national level."

Advertisement

This thesis needs more work — especially on the ways elite institutions and popular imagination interacted as these acids of modernity ate away at the very concept of transcendence. It is critical to our understanding not only of our shared history but of the moment in which we find ourselves today.

The diminution of religion as a source of cultural authority is evident, and it is increasingly difficult to make the case that it has been a boon for society. Not for the first, or last, time have elite institutions of culture formation headed far down the wrong path! But, let's not get ahead of ourselves. I will wrap up my review of this important book on Monday when we will examine Hunter's profound and provocative assessments of our political polarization and its cultural sources.