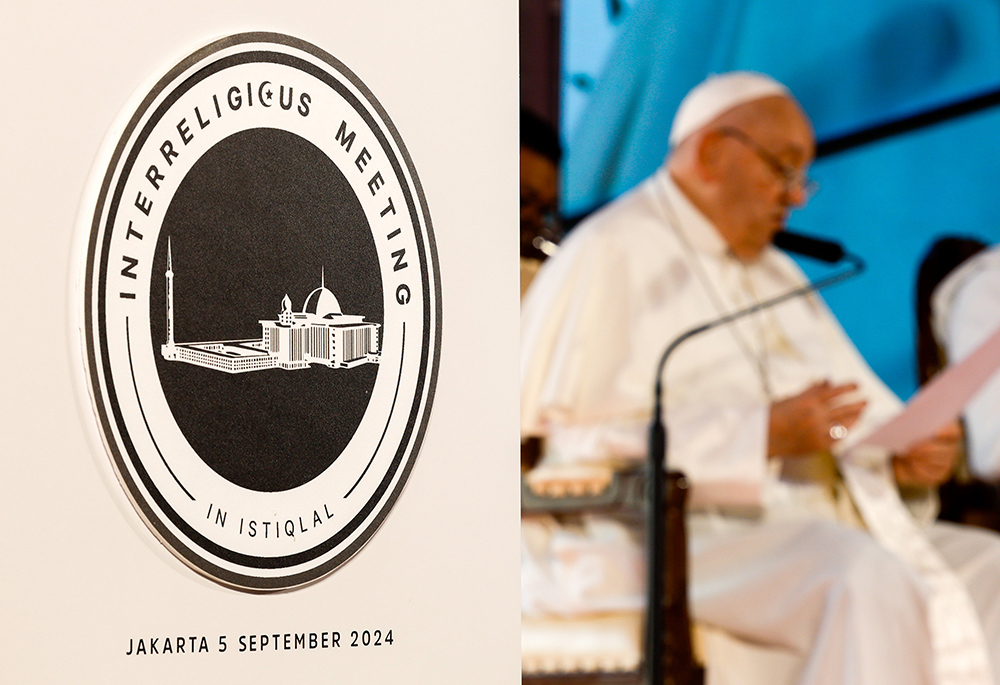

Pope Francis speaks to representatives of Muslim, Christian, Hindu, Buddhist and other religious communities during an interreligious meeting at the Istiqlal Mosque in Jakarta, Indonesia, on Sept. 5. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

Pope Francis, in his address to an interreligious gathering at the Istiqlal Mosque in Jakarta, Indonesia, on Sept. 5, called attention to the "tunnel of friendship" which connects the mosque with the nearby Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption. He called it an "eloquent sign" of the culture of encounter that has been central to his ecclesial vision, as well as key to Indonesia's history of relative peacefulness among the various religions that coexist within the vast archipelago.

"[T]his passageway allows for encounter, dialogue and a real possibility for 'finding and sharing a "mystique" of living together, mingling and encounter […] stepping into this flood tide which, while chaotic, can become a genuine experience of fraternity, a caravan of solidarity, a sacred pilgrimage' [apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, Paragraph 87]," the pope said. "I encourage you to continue along this path so that all of us, together, each cultivating his or her own spirituality and practicing his or her religion, may walk in search of God and contribute to building open societies, founded on reciprocal respect and mutual love, capable of protecting against rigidity, fundamentalism and extremism, which are always dangerous and never justifiable."

In the West, we look back at the 16th-century wars, fought in part over religion, and some people think religious fervor inevitably leads to conflict. John Lennon's "Imagine" gives voice to the sentiment: "Imagine there's no countries/ It isn't hard to do/ Nothing to kill or die for/ And no religion, too." In truth, it is hard to imagine a world with no countries; there are things worth dying for and imagining a world with no religion fills me with dread, not dreams. And the 16th-century sociocultural landscape had a lot of moving parts of which religion was only one.

Nasaruddin Umar, grand imam of the Istiqlal Mosque in Jakarta, Indonesia, kisses Pope Francis on the top of the head at the conclusion of an interreligious meeting Sept. 5. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

It is also true that flying airplanes into buildings is not something likely to be done by a zealot motivated by mere terrestrial or quotidian ambitions. I do not suppose fighting for an increase in the minimum wage or against higher capital gains taxes would be enough to motivate someone to such fanaticism. The terrorists who murdered some 3,000 people on 9/11 were told to shout "God is great." Theirs was a religious act. Blessings on the grand imam in Jakarta for welcoming the pope and for being a voice of irenicism and solidarity.

After the attacks on 9/11, Frontline interviewed many people. One of them was Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete. "From the first moment I looked into that horror on Sept. 11, into that fireball, into that explosion of horror, I knew it," he recalled. "I knew it before anything was said about those who did it or why. I recognized an old companion. I recognized religion."

Albacete also recalled the image of two people holding each others' hands as they jumped from one of the burning towers. "To me, that image is an inescapable provocation. This gesture, this holding of hands in the midst of that horror, it embodies what Sept. 11 was all about," he said. "The image confronts us with the need to make a judgment, a choice. Does it show the ultimate hopelessness of human attempts to survive the power of hatred and death? Or is it an affirmation of a greatness within our humanity itself that somehow shines in the midst of that darkness and contains the hint of a possibility, a power greater than death itself? Which of the two? It's a choice."

Advertisement

Pope Francis spoke to that choice in his speech. He said:

… always look deeply, because only in this way can we find what unites despite our differences. … We could say that what lies "underneath", what runs underground, like the "tunnel of friendship", is the one root common to all religious sensitivities: the quest for an encounter with the divine, the thirst for the infinite that the Almighty has placed in our hearts, the search for a greater joy and a life stronger than any type of death, which animates the journey of our lives and impels us to step out of ourselves to encounter God. Here, let us remember that by looking deeply, grasping what flows in the depths of our lives, the desire for fullness that dwells in the depths of our hearts, we discover that we are all brothers and sisters, all pilgrims, all on our way to God, beyond what differentiates us.

Too often, interreligious dialogue gets worried about conflicts over doctrine, and ends in a kind of lowest common denominator ethical stance or political activism. Instead, the pope invites us to look to the depths of our humanity where we discover "the thirst for the infinite that the Almighty has placed in our hearts."

Accompanied by Nasaruddin Umar, grand imam of the Istiqlal Mosque, Pope Francis visits the Tunnel of Friendship as part of an interreligious meeting in Jakarta, Indonesia, on Sept. 5. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

It is counterintuitive in our rationalistic age to suggest that it is in desire that we find commonality and a path to mutual respect. Romanticism, Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 notwithstanding, was drunk on desire and it did not lead to universal peace and goodwill. It led to an extravagant belief in the importance of belonging, and thence to nationalism and fascism. The depth of the religious desire must invite a humility about our role in the divine economy, as well as demanding a humanistic (and, therefore rational) approach to religion in the world. You cannot ever affirm the divine by murdering humanity, never. Pope Francis' gestures of friendship at the mosque are the antithesis of religiously inspired hatred.

The tunnel of friendship is a wonderful thing, but the proverbial rubber hits the road in Jakarta in the fact, reported by NCR's Vatican correspondent Christopher White, that the Istiqlal Mosque and Cathedral of the Assumption also share a parking lot. Religious dialogue can sometimes sound pie-in-the-sky, and what is way up there often has little binding force in life's daily claims. In Jakarta, the mosque and the cathedral share a parking lot. I love that. If you have ever been stuck in the great city's traffic, you know that by the time you reach your destination, frustration is your companion. In the tunnel, Muslims and Catholics can plumb the depths of their shared humanity. In the parking lot, they bear each other's frustrations.

These papal trips around the world are a source of ambivalence. They turn the pope into a celebrity, but his authority resides in the fact that he is the successor of a martyr. On the other hand, they are a shot in the arm to the local church. An added value is found in the pope's address at the mosque. He could have said the exact same words in Rome, and who would have noticed? But at a mosque in the most populous Muslim nation on earth, they reach a wider audience. They invite all of us Catholics to think about how we encounter persons of other religions. The invitation to look deeply, not to be afraid of whatever doctrinal differences might separate us, is a really important point and should shape interreligious dialogue in the years ahead.