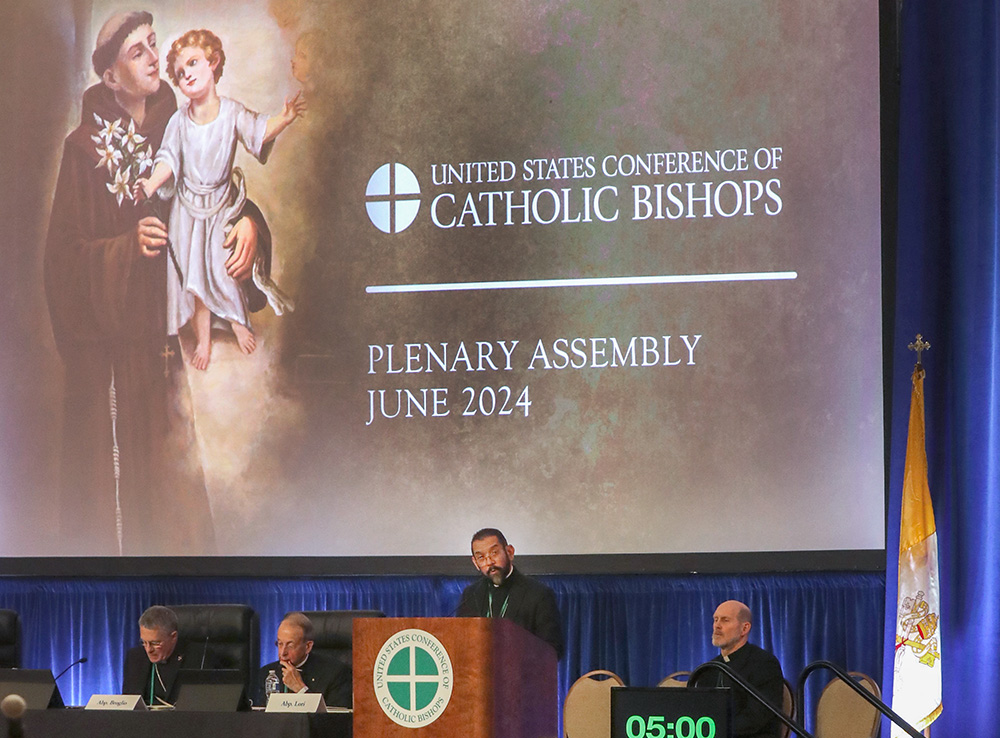

Bishop Daniel Flores of Brownsville, Texas, speaks June 13 at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' Spring Plenary Assembly in Louisville, Kentucky. (OSV News/Bob Roller)

In Louisville, Kentucky, last week, many bishops complained about the thinness of the agenda for their spring meeting. Apart from the debate over the future of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, the church's antipoverty program, did they really need to spend the time — and the expense — of this trip? It is such an exciting time in the life of the church. Why did this meeting feel somnolent?

As my colleague Brian Fraga reported, the biggest news to emerge from the conference was the overwhelming support for the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. This is great news. One bishop told me that he thought it marked a "turning point" for the conference. The critics of the program, such as the Lepanto Institute, have been exposed as the outliers they are. This is all to the good.

Still, there remain signs that the bishops' conference is operating at a significant distance from the leadership of Pope Francis.

For example, in his address, Military Services Archbishop Timothy Broglio, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, discussed the synodal process, but it is less clear he grasps it. He said, "The experience of the synod taught the participants the importance of listening to the other even as we seek to proclaim the unique Gospel of Jesus Christ. The message of truth cannot be altered, but in every age we find ways to bring it to the ears of others."

This framing raises questions about his understanding of synodality. It makes it seem as if the listening is almost incidental to the task of proclaiming the Gospel: "Even as" suggests parallel tasks, not a properly ecclesial approach.

Broglio's characterization also makes it sound like synodality is a one-way, top down, approach, from on high to those below. There is no sense that the proclamation of the Gospel can sometimes start with the people of God and move up to reach the bishops.

Advertisement

To be clear, bishops are allowed to have an entre nous conversation just like other groups of colleagues. In the synodal process, we are all called to surrender ourselves to the Spirit, but the bishop surrenders as a bishop and the layperson as a member of the laity. We all get that.

Still, it is pretty difficult to look at the last few decades of the life of the church in the United States and not conclude that sometimes it is the bishops' ears that have needed the Gospel brought to them.

Ours is a nation with a long tradition of democratic governance. Majority rules. But the bishops' conference in the U.S. has long been characterized by the need to forge consensus, as were the deliberations and decisions at the Second Vatican Council, where the final texts were passed by overwhelming numbers.

The most contentious measure at the council was the Decree on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis Humanae, but it received the support of 1,997 to only 224 opposed. When the U.S. bishops adopted their pastoral letter on war and peace in 1983, only nine bishops voted against the final text.

It was good to learn that there was such a strong consensus to preserve the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. It would have been better if the discussion had occurred in open session so that the whole world would see that a consensus had been reached.

Bishop Daniel Flores of Brownsville, Texas, has been leading the synodal process in this country and he thanked the bishops for their participation in the effort, as well as the many people at the diocesan level who have participated and shepherded the process.

Flores does grasp the synodal method. He spoke about his ministry to migrant communities, which he noted are often "poor and very isolated." He said, "We ask them first, 'What do you need?' and often the first answer is simply 'No te olvides de nosotros,' ''Do not forget about us,' " he said. "Hearing this is both sobering and challenging. … We must be willing to learn from them."

Flores grasps the power of synodality to let the witness of the poor inform the universal church.

Kerry Robinson addresses the U.S. bishops June 13 during their spring assembly in Louisville, Kentucky. (OSV News/Bob Roller)

Another person who clearly grasps the synodal process is Kerry Robinson, president and CEO of Catholic Charities USA. She spoke to the bishops about the mental health challenges of our time and what the church is doing and can do to address it.

She called attention to the "alarming" statistic that one in four Americans need mental health support but only one in 50 have access to a trained professional. She noted that Catholic Charities provided mental and behavioral help to 600,000 Americans last year, which is an amazing accomplishment, but the need is so much greater.

Robinson then invited the bishops to undertake small-group discussions at their table and "jot down salient insights and recommendations from your table discussions."

Before turning to those small-group discussions, she invited the bishops to pray. "Let's take one moment of silence, to be mindful of the presence of the Holy Spirit, holding in our hearts all who have been impacted by challenges to mental health," she said. You could hear a pin drop.

In thinking about synodality, it is vital, absolutely vital, to remember that our listening must be a prayerful listening. Robinson remembered.

The rest of the meeting was mostly a yawn. There was an interesting discussion about the ministry of catechists, with some understanding the danger of clericalizing the ministry, and others failing to see that such ministries can serve as a means for pulling down the wall that is clericalism. The bishops adopted a letter on Indigenous ministry. Some additional translations to liturgical texts were approved. Bishop Mark Seitz gave an excellent speech rooting our concern for migrants in our Catholic promotion of human life and dignity, and highlighting the need for expedited visa programs, for foreign-born clergy and for all migrants.

What will it take for the U.S. bishops' conference to become a vehicle for incorporating the vision of Francis for a more synodal church, one capable of deepening an ecclesial self-understanding by attending to the poor and most vulnerable in our midst?

This meeting in Louisville offered some signs that the bishops, as a whole, are increasingly attuning themselves to the pope's lead. But the bishops are not there yet and they won't be until there is new leadership at the bishops' conference.