Evening light shines on a crucifix in the vestibule of St. Paul's Basilica in Toronto in this 2008 file photo. In his new book, James Keenan begins his narrative with the New Testament. Keenan sees the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ as offering the exemplar of moral living. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Enter the world of Jesuit Fr. James Keenan's classroom, where he crafts and delivers a gripping tale of the historical development of Catholic theological ethics from the beginning of the church to date. For someone who does not self-identify as a historian, Keenan cuts a profile of a "fully trained disciple" (Luke 6:40). His superior mastery of the complex history and tradition of moral theology buoys his readers along two millennia of crests, ebbs and flows. The reader is not drowned in the arcane, abstract and speculative, because throughout the book Keenan parades captivating innovators, actors and protagonists that have shaped the growth and progress of theological ethics.

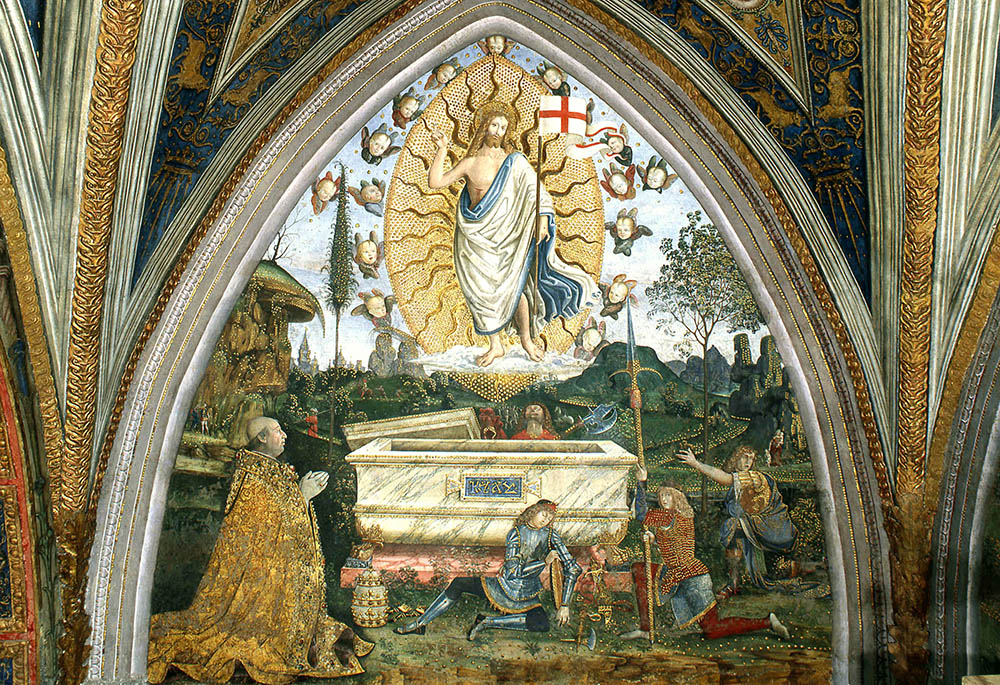

Keenan begins his narrative with the New Testament; it is the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ that he sees as offering the exemplar of moral living. By locating the foundation of theological ethics in the New Testament, Keenan demonstrates that it is a faith-based enterprise that can neither be understood nor practiced outside of the life, teaching and mission of Jesus Christ. The "Christ event" is the foundation, background, standard, reference and impetus for moral living.

Keenan outlines how the early Christian communities lived the moral life as a response to the call of the word of God to discipleship as individuals and as a people. This approach is a far-cry from the fundamentalism of Scripture as a proof text, because ethical teaching in the New Testament is not merely about words, but about how believers as the body of Christ should live. Foundational orientations like love, mercy and discipleship make sense only in light of Jesus' self-understanding as the reference for Christian moral self-understanding.

Reading history "as it was," Keenan avoids the temptation of projecting late ideas into history and helps the reader to make sense of the historical development and evolution of theological ethics. His narrative departs significantly from a Eurocentric reading of tradition and history and presents an inclusive account, precisely because the traditions of theological ethics are the work of a community. He masterfully assembles the cast of this community in a single readable volume, across an extended arc of history and a vast geographical space, to demonstrate the growth, decline and progress in biblical ethics, sexual ethics, medical ethics and social ethics.

Renaissance master Pintoricchio’s fresco of "The Resurrection" in the Vatican's Borgia Apartments is seen in this 2013 photo provided by the Vatican Museums. (CNS/Courtesy of Vatican Museums)

Keenan pays attention to turning points, milestones and towering personalities, but also hidden figures, no less influential in shaping the contours of moral theology. He helps us appreciate both the flaws and "positive features" of their approaches by integrating their biographies into his narrative to show us where they are coming from. One aspect that Keenan flags as a gap and which he strains to fill is the neglected stories of women. Women played a pivotal role in the history and development of theological ethics, a field that "was being shaped by men for men based on their self-understanding."

Moving from the NT foundation, Keenan explores the historical contexts of the development of ethical questions and issues. His fulsome treatment of the traditions of the works of mercy as moral practices of Christian disciples and the virtues of hospitality, chastity, solidarity, mercy and happiness reveals refreshingly new insights. Although Keenan is careful about inserting himself into the story, we see snippets of his own innovation and creativity and contribution towards the liberation of conscience. Mercy, says Keenan, is "willingness to enter into the chaos of another" and sin as "failure to bother to love."

You won't find a more fascinating account of the history and tradition of sin. Keenan explores its various specific historical understandings through which we see the rise and fall of traditions, schools of thought and their champions. Sin is measured with a sophistication that attains a bewildering height of absurdity in the penitential manuals.

As for sex and sexuality, it is an altogether different story. The treatment of sex is always linked to specific questions and contexts. But sex is ubiquitous and the obsession with sexuality has always threatened to derail moral theology as both a call to discipleship and a pathway to holiness. This vexing issue in the history of moral theology provokes an "unequivocal intolerance in moral tradition." Along with sin, the history of the understanding of sexuality is an "enormous arc" whose end is still far from visible.

But beyond the copious details of personalities, dates, times, events and concepts, the reader will find most beneficial the idea that moral principles and practices, norms and criteria make sense within a bigger picture or a pathway to holiness. No matter how this dynamic path and its ethical imperatives were variously interpreted by professional theologians, embodied by practitioners, debated by competing schools and modeled by exemplars, formation for moral life lies at the heart of moral theology.

Advertisement

The direction of this pathway oscillates between holiness, like striving for union with or imitation of Christ, and absurdities, like the fixation on sex. Some shifts are pivotal, such as from privatized morality to "discipleship by prayer and good deeds" for all. In time, the pathway to holiness moved from desert caves to urban centers. Keenan does not hide his predilection for historically minded theologians who discover the objectivity of truth in history and context and are open to progress.

The author makes his narrative engaging and enjoyable by synthesizing and simplifying key principles and concepts to render them accessible to today's readers. His numbered summaries, syntheses and conclusions on major contributions, eras, themes and subjects in practically every section of this book makes his narrative easy to follow; even if his treatment of 16th-century casuistry is dense, labored and almost sours its promised "foretaste."

But Keenan saves the best for last. When he comes to our own time he unveils the dramatic flourishing of theological ethics, the face of which now reflects "the more common features of everyday Catholics": a dazzling collage of innovative lay women and men, married and committed, in the academy and in the church.

The book's concluding storyline of how theological ethics is evolving into a cross-cultural discourse is electrifying. Keenan's revelry in this absorbing narrative is understandable because he is telling the story of the emergence of Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church, a group that Keenan almost singlehandedly originated. A History of Catholic Theological Ethics is a book by an author who can be trusted.