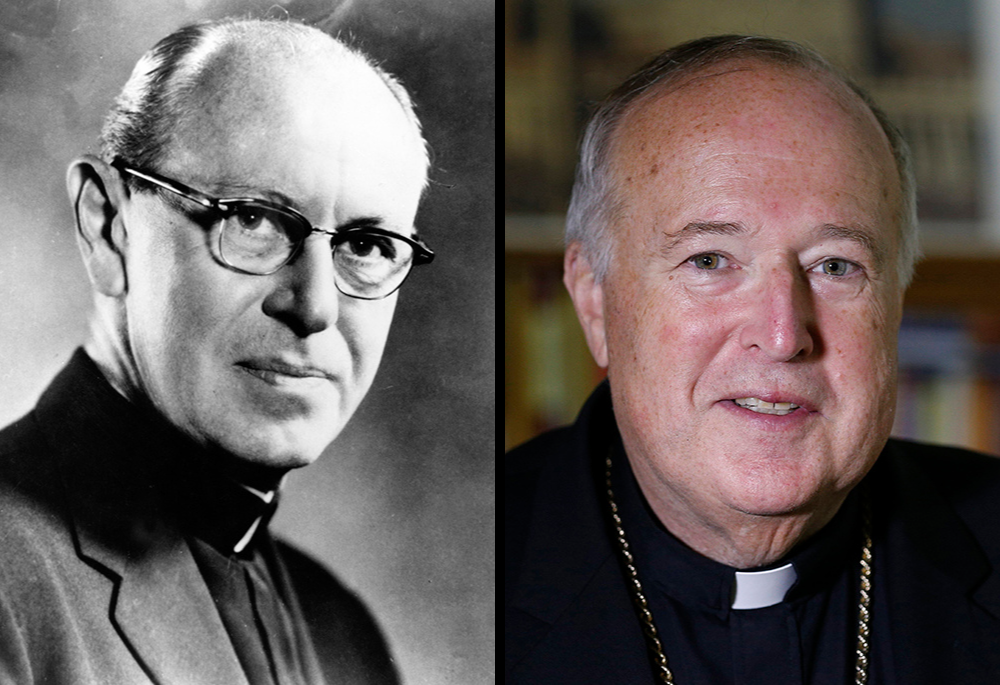

Jesuit Fr. John Courtney Murray, left, is pictured in an undated photo; at right, Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego is pictured after an interview with Catholic News Service Oct. 27, 2019, in Rome. (CNS files/Paul Haring)

At tomorrow's consistory for the creation of new cardinals, Pope Francis will bestow a titular church on each of them, making them honorary members of the clergy of Rome. It is in this capacity that they will someday enter the conclave to elect Pope Francis' successor, as an honorary pastor in Rome.

We do not know what church San Diego's Cardinal-designate Robert McElroy will get, but this symbolic ritual points to an historic link between this consistory in the third decade of the 21st century and a consistory in the penultimate decade of the 19th century.

James Gibbons, the archbishop of Baltimore, was created a cardinal at a consistory on March 17, 1887. On March 25, he took possession of his titular church, Santa Maria in Trastevere. One of the oldest churches in the city, and a rival with Santa Maria Maggiore for the honor of being the first church dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, Santa Maria in Trastevere started as a house-church during the reign of Pope Callixtus I (217-222). The following century, Pope Julius established a larger structure with the current floor plan and walls, although most of the structure we see today dates from 12th-century renovation.

Gibbons used the occasion of his taking possession of the church to deliver a robust defense of the approach to church-state relations found in the U.S. Constitution. "[W]ithout closing my eyes to our shortcomings as a nation, I say, with a deep sense of pride and gratitude, that I belong to a country where the civil government holds over us the aegis of its protection, without interfering with us in the legitimate exercise of our sublime mission as ministers of the Gospel of Christ," the new cardinal affirmed. "Our country has liberty without license, and authority without despotism."

As U.S. church historian Gerald Fogarty observed, "Here was the gauntlet of the benefit of American religious liberty thrown down by the new world to the old, which could not understand it until the Second Vatican Council."

This was a time when "a free church in a free state" had been the motto of Camillo Cavour, the founding prime minister of united Italy and archnemesis of Pope Pius IX. Pope Leo XIII would bring new life to Catholic social doctrine, but on the issue of religious liberty, he would not be moved. In 1899, his encyclical Testem Benevolentiae specifically condemned "Americanism." Religious liberty was still a condemned doctrine and would remain so until Vatican II.

Advertisement

The great Jesuit theologian John Courtney Murray was the man most responsible for rehabilitating American ideas of religious liberty and reintroducing them into the Catholic theological conversation before and at Vatican II. Not without controversy! Murray was silenced by Rome in the 1950s and forbidden to write or teach on the subject of religious liberty. When the new building at the North American College was dedicated by Cardinal Samuel Stritch in 1953, the cardinal’s remarks consisted of a short toast to religious liberty and no more. In a letter Murray wrote to Msgr. John Tracy Ellis, he recalled Stritch saying, "None of us could go as far as Gibbons went." Murray told Ellis he wanted to shout out, "Why not?"

Murray was not originally invited to be a theological expert at the council, but Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York brought him as a peritus for its second session. It is misleading to say that Vatican II endorsed America's separation of church and state. Murray's desire to have the council endorse a negative conception of freedom, a "freedom from," was modified: Freedom, for Catholics, cannot be so severed from truth as the American Constitution allows. Still, it is far from clear the issue would have even made it on the agenda had not the American bishops pushed for it. Throughout the council, the draft text on religious liberty was known as "the American schema." Murray's ideas, though modified, were vindicated with the adoption of Dignitatis Humanae by the council fathers.

San Diego Bishop Robert McElroy greets artist Jim Bliesner Oct. 5, 2018, next to a miniature replica of a statue Bliesner is creating in honor of immigrants and refugees during a ceremony in San Diego. (CNS/David Maung)

Cardinal-designate McElroy is one of the nation's leading experts on Murray's theology. McElroy's 1989 book The Search for an American Public Theology: The Contribution of John Courtney Murray is an outstanding contemporary study of Murray's influence. I do not entirely share McElroy's enthusiasm for Murray, but there is little doubt that no bishop has been more articulate about the need to protect religious liberty, and to do so without using it as a bat to beat other people over the head, still less to shirk the responsibilities of civic life in a diverse, pluralistic society and culture.

The ceremony tomorrow (Aug. 27) will symbolically reach back to that day in 1887 when Gibbons could speak boldly about religious liberty. Unfortunately, Pope Francis cannot give McElroy Gibbons' church. The current archbishop of Madrid, Cardinal Carlos Osoro Sierra, is the titular at the ancient church in Trastevere. Nor will McElroy be able to take possession of whatever church he is given this weekend.

But, like Gibbons before him, he joins the rank of the College of Cardinals at a time when the relationship of the Catholic faith to religious liberty is contested, and Pope Francis could not have chosen a better man or a better mind to help guide that discussion along fruitful paths.