St. Mark the Evangelist’s symbol is the winged lion, the Lion of St. Mark, which is also the symbol of Venice, in background. This image by Vittore Carpaccio is in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. (Image courtesy of Creative Commons)

There is something exciting about living in extraordinary times — times of surprises, special events and even challenges. These are the days when it is easier to get out of bed in the morning. You have something to look forward to.

Ordinary times, on the other hand, can be boring.

Last week Catholics and other Christian churches began "Ordinary Time," that part of the liturgical year that is not Advent, not Christmas season, not Lent and not Easter time. Technically, it is called "ordinary" not because it is unspectacular, but because the weeks of the year are numbered, as in ordinal numbers (first, second, third, etc.).

Despite the origin of the word, Ordinary Time can appear, well, ordinary. But Ordinary Time is also a time for getting back to basics, for taking on projects that will make us better Christians.

There are few projects more important for Christians than getting back in touch with the Gospels. Sadly, 63 percent of Catholics read the Bible less than once a month, according to the Pew Forum. Ordinary Time is a good time to get in the habit of reading a little bit of the Gospels every day.

An easy way of doing that is by reading or listening to the Gospel from the Mass of the day. You can also ask Alexa to "Get Catholic Daily" or look in your podcasts for "Daily readings from the American Bible."

The Gospel reading used at Mass on Jan. 14, Monday of the first week in Ordinary Time, was the beginning of Jesus' public ministry as described by Mark. As the weekdays of Ordinary Time progress, Catholics hear successive passages from Mark's Gospel. We will get through 10 chapters of Mark before reaching Lent on Ash Wednesday, March 6.

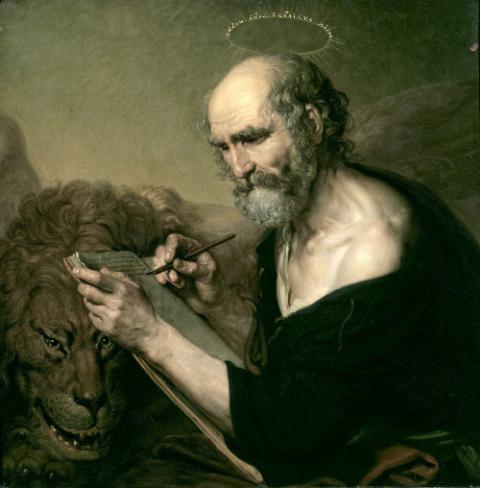

St. Mark the Evangelist, by Vladimir Borovikovsky, from the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg, Russia. (Image courtesy of Creative Commons)

With the choice of these readings, the church is telling us that it is time to get reacquainted with the Gospel of Mark. After Pentecost, when Ordinary Time returns, the weekly liturgical reading will reintroduce us to Matthew, and then Luke.

When I was in high school, a teacher told us we had to read one of the Gospels, so we all read Mark because it was the shortest, not knowing that it was also the earliest of the four canonical Gospels to be written down.

Mark's Gospel has no infancy narrative. It begins with the preaching of John the Baptist and his baptism of Jesus in the Jordan. All of this, plus the temptation in the desert, is covered in only 13 verses of the Gospel before Mark begins describing the public ministry of Jesus.

"The kingdom of God is at hand," announces Jesus.

He then shows what the kingdom of God is about through his teaching and his compassion for the possessed, the sick and sinners. And he demands a response: "Repent, and believe in the gospel."

People liked Jesus' miracles but when he started forgiving sins, opposition arose from the traditional religious establishment. This opposition is a central theme of Mark's Gospel. It reminds me of the opposition to Pope Francis from traditionalists when he wants to reach out to gays and divorced and remarried Catholics.

But it is not only the establishment that does not accept Jesus. According to Mark, nobody understands Jesus, not even his disciples. Mark's low opinion of the disciples makes him the first anti-clerical Christian.

A St. Mark the Evangelist icon by Emmanuel Tzanes from 1657. (Image courtesy of Creative Commons)

By Mark's third chapter, it's clear that nobody really gets Jesus, not even his mother and relatives. Mark is a misanthrope. He has a very low opinion of humanity.

Mark believes that Jesus calls for a radical commitment that will change our lives forever. If we are unwilling to do that, we don't understand what Jesus is asking of us. Mark looks at his fellow Christians and finds them wanting.

This explains why Mark's Gospel originally ended with the empty tomb, not with the appearance of the resurrected Jesus.

The women are informed of the resurrection by a young man "clothed in white," who tells them to inform Peter. Instead, they "fled from the tomb, seized with trembling and bewilderment. They said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid." The end.

The Gospel of Mark ends with a failure of belief, a failure of commitment. Not even with the resurrection did the disciples understand Jesus.

This ending was such a downer that later scribes added resurrection stories (Mark 16:9-20). They wanted a happy ending.

Early Christian communities were not happy with Mark's negative view of the early Christians. He wanted them to be perfect, but they were not. They believed and committed themselves to Jesus, but they also continued sinning.

They understood that the Christian life is not just one decision for Jesus; it is a lifelong journey in which we can get lost along the way.

Matthew and Luke rewrote the Gospel of Mark because the Christian community needed a Jesus who would not just demand their belief and commitment but one who would also nourish and sustain them for life's journey. They needed a Jesus who would pick them up when they fell.

Advertisement

If the early Christians found Mark's Gospel wanting, why did they not just throw it away?

They couldn't do it. They knew deep in their hearts that we need to hear what Mark has to say. They knew that if we really believed Jesus it would radically change our lives.

Mark is a nag, but we need him to keep us honest, to keep us from being self-satisfied in our Christianity. We need Mark to remind us that we are failures, but we need the other Gospels to help us through our failures.

I hope this does not discourage you from reading Mark. We need to hear his challenge. His job during Ordinary Time is to keep us from being ordinary.

[Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese is a columnist for Religion News Service and author of Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.]