The Rose family of "Schitt's Creek" (from left): Catherine O'Hara as Moira, Annie Murphy as Alexis, Eugene Levy as Johnny, and Daniel Levy as David (Newscom/Album/CBS/Not A Real Company)

I came to "Schitt's Creek" during the pandemic, a little numbed by the condition of the world and the limits of life on Zoom.

I give a platelets donation every Friday at the Red Cross, where they take blood out of one arm, spin it through a centrifuge to separate out the platelets and then return the whole blood and plasma to your other arm. You're strapped into a recliner where you can't move, with needles in your arms for about two hours, enough for six episodes of "Schitt's Creek."

After the second week of binging like that, the Red Cross nurses prohibited my binge because I was alternately laughing and crying so hard that I was jostling the very large needles in my arms, which is dangerous, and because I was strapped in, they were having to wipe my eyes and nose, which was annoying.

Theology (and I should be very clear that I mean theology in general, not the Catholic Church or any other particular faith tradition) can learn a lot from a show like "Schitt's Creek" about emotion, the role of suffering, human interdependence and love as self-gift, or agape.

The show offers us about a gazillion invitations to pay attention to human emotions.

There is a lot of raw and hysterically funny emotion on Schitt's Creek: "Fold it in!"; "Into the wine, not the label!"; "You're simply the best ..."; "Ew, David!" Despite our venerable tradition in the West of separating our emotions from our rational thoughts, and elevating reason above other ways of leaning into the world, even in theology — the study of humanity's relation with the divine — paying attention to our emotions makes us more human. They are at the very core of what it means to be human, humane. Emotions are our burning bush, taking over where words fail, and "Schitt's Creek" is an all-you-can-eat buffet of emotions.

Brianna Wiest, who writes about emotional intelligence, exhorts us to pay attention to our emotions as the crucial messengers they are. She writes:

Your anger? It's telling you where you feel powerless. Your anxiety? It's telling you that something in your life is off balance. Your apathy? It's telling you where you're overextended and burnt out. Your feelings aren't random, they are messengers. And if you want to get anywhere, you need to be able to let them speak to you, and tell you what you really need.

"Schitt's Creek," and the laughter and tears it extracts from us, can be cleansing, pointing us to what we need to pay attention to, and help make us vulnerable in some pretty life-giving ways.

Advertisement

The show also provides some pretty satisfying responses to the problem of evil and suffering in the world. The Rose family's world shrinks overnight from a palatial estate to two adjoining motel rooms in a tiny rural town. Their identities — how they see themselves in relation to the world — are stripped. Their purpose is completely unclear.

We might laugh at Moira's anguished screaming at the fate of her bébés — her wigs — but what she is experiencing is true anguish for her. David speaks often throughout the series of his lifetime suffering, feeling he is a joke with no friends — "damaged goods," in his own words. Alexis's myriad exotic beaus and her posse of girlfriends are reduced to silent old text addresses on her bedazzled cellphone when she suffers the realization that they have abandoned her. Johnny goes from tycoon patriarch/provider to a man with no place to be.

But as they confront, not avoid, their new reality and allow themselves to flex new muscles — or rather old, atrophied muscles (recall how hard those early hugs were for David and Alexis?) — new tendrils of life start to curl into their world.

Johnny fixes — sort of — the first faucet of his life. Moira lends a definite and welcome aesthetic to the town, and changes lives with her mentoring. David incubates an idea for a new business that draws together the art, craft and ingenuity of his new town into Rose Apothecary, which will also usher in the great love of his life. At age 28, Alexis endures another round of high school and creates an entrepreneurial path for herself at the local college. We leave her in the finale on the brink of striking out on her own into the world of PR in New York City.

The Schitt's Creek Motel sign as featured in the television series (Dreamstime/Bobhilscher)

How can a loving and all-powerful God allow innocent people, or even those seen often as not so innocent like the Roses, to suffer? The lack of a satisfying answer to this very human question is really tough on the discipline of theology and the practice of religion. It can't help that most of us do our darnedest to avoid pain and suffering.

In the long arc from losing everything to finding (or rekindling) enduring love and fulfilling work for all members of the Rose family, "Schitt's Creek" — probably without meaning to — embodies the possibility that enduring some suffering, the thing we least want to have happen in our life, is a pathway into new life and flourishing.

"Schitt's Creek" shows the suffering we endure can purify and strengthen. It allows us to re-frame suffering as a painful experience that can be a pathway into empathy and outreach to another human being who suffers.

Stevie Budd has, by her own admission, been living a life of quiet desperation, stuck behind the desk of a shabby little motel. All the Roses see strength and potential and coolness in her.

One of the "Schitt's Creek" moments I play over and over is Stevie's rendition of "Maybe This Time" in the town's staging of "Cabaret." The exultation that grips her at the end of that number is riveting. She did it — the very thing she yearned for yet fearfully avoided!

The power was in her all along, but it took the fruits of Moira, Johnny, Alexis and David's own suffering to coach her to that triumph. The show offers a gentle vision of the generative potential of enduring and learning from our suffering, and that could be a fantastic tool for theology.

Additionally, "Schitt's Creek" beautifully portrays the power of human interdependence.

One of the remarkable things about the series is how prevalent and unremarkable diverse faces, colors, shapes and sizes are in this tiny town. The Jazzagals have black and white and brown and big and petite women all contributing to their harmonies, seemingly effortlessly. Audiences fill up venues for their friends anytime they are on stage.

Patrick can sing to a packed coffeehouse crowd his slow cover of "You're Simply the Best" to David — who can lip-synch and shimmy it right back, Tina Turner style — in Rose Apothecary in the middle of the day, visible to the entire town, without any apparent fear of being attacked by anyone threatened by their love.

It shows what a truly inclusive, interdependent community looks like, without sermonizing or beaming a spotlight on it.

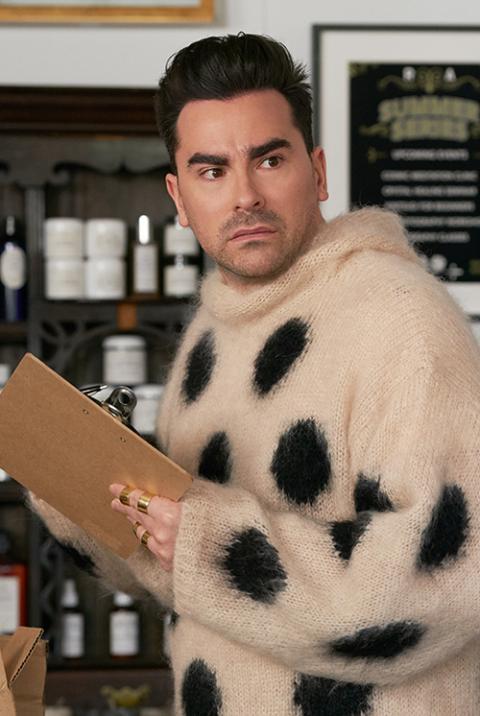

Daniel Levy as David in "Schitt's Creek" (Newscom/Album/CBS/Not A Real Company)

We see vivid, frequent examples of people showing up where they're needed. Someone rescues 47 wigs from a burning motel room; another character promises to cherish forever a partner who has spent a lifetime considering himself to be "damaged goods." We see these not because of a petition, theological treatise or a sermon, but because that is what "beloved community" looks like.

If we need saving, your job is to see those hands extended and leave aside fears of vulnerability and of being diminished somehow by being on the receiving end of help — of saving grace, as the Rose family attorney invites them to consider in the first five minutes of the entire series.

Near the end of his most recent encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis argues that forgiveness and charity (both the giving and the receiving) are way more muscular than they get credit for. They're not about rolling over and being a doormat, but choosing not to yield to the same destructive forces that have caused our suffering.

In "Schitt's Creek," we see a place where people show up for one another and do what's needed to allow each person to flourish according to their gifts and then plow those gifts back into the community as they are needed.

One of the most consistent sources of happy-crying on "Schitt's Creek" are the occasions when a character puts their own interests aside so that someone they love will flourish.

Alexis is kind of amazing at this — humbling herself to Ted's new girlfriend in order to open up an important business opportunity for her brother, David. She is always the first person to embrace another and say those fearsome, powerful words, "I love you." And of course (spoiler alert!) that five-hankie scene at Twila's Café in which Alexis and Ted, two people who adore each other, surrender their claims on the other person so that each can truly flourish — the end of a love story where the love does not end, but is transmuted into something glorious and fruitful. This is a powerful illumination of what agape love, love as self-gift, can bring about.

Many times, we see "Schitt's Creek" characters' hearts and spirits shatter into shards, only to be picked up and refashioned into something even more beautiful by a person who makes an unselfish decision to love without reservation.

Moira Rose will never fade quietly into the background as she empties herself into the town; David's singular fashion sense never acquiesces to Patrick's button-down shirts and Dockers; Alexis will forever have too many suitcases and annoying mannerisms — but Schitt's Creek offers a bracing counter-example to those of us who might avoid generosity for fear of losing ourselves.

In the end, "Schitt's Creek" is all about love, and love is all about how we treat ourselves, God and one another. It takes a lifetime to unpack that, and good companions along the way make the journey anything from bearable to joyful.

"Schitt's Creek" might only guarantee you 23-minute blocks of escape from our very bruised world. Or it might give you a glimpse into the Divine, where emotions, generative suffering, interdependent humanity and agape love reign.