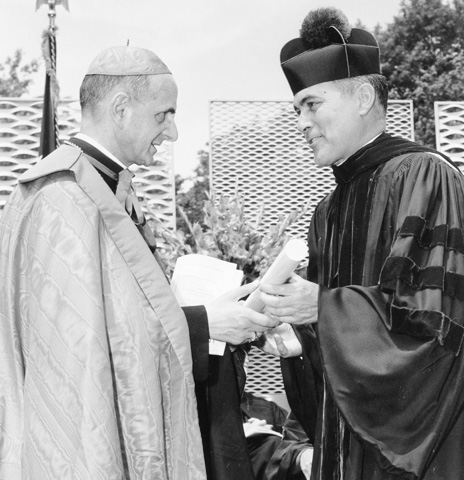

Archbishop Giovanni Battista Montini of Milan, the future Pope Paul VI, and Holy Cross Fr. Theodore Hesburgh shake hands in South Bend, Ind., in 1960. (CNS)

Editor’s note: Robert Sam Anson, the journalist who credited the late Fr. Theodore Hesburgh with his release from captivity in Cambodia 50 years ago, died last week in Rexford, New York. In 2015, shortly after Hesburgh, the former president of the University of Notre Dame, died at age 97, Anson made available to NCR a collection of material documenting his rocky relationship with Hesburgh over the years. Tom Roberts, then NCR’s editor-at-large, compiled the report re-published here. Anson also figures in the documentary film about Hesburgh reviewed last year by Sr. Rose Pacatte.

Holy Cross Fr. Theodore Hesburgh knew for some time that among the appreciations and reflections following his death would surface one quite different from all the rest.

It appears here, largely in the words of Robert Sam Anson, a 1967 University of Notre Dame grad who went on to a high-profile career in journalism and who had a lifelong relationship with Hesburgh, the legendary Notre Dame president who died Feb. 26 at age 97. It was a relationship marked both by deep reverence for the priest, a person Anson still refers to as "the only father I ever had," as well as by sharp exchanges over several controversies and Hesburgh's leadership style.

For all the tension in the relationship (Anson's own mother and his sister, a nun at the time, wrote to Hesburgh suggesting he kick Anson out of the university), the priest not only kept him on but was also instrumental in helping to save Anson when he was later captured while covering a war.

In 2006, Hesburgh granted Anson an interview with the understanding that its contents would not be published until after the priest's death.

Anson provided NCR with descriptions of his student days, his first meeting with Hesburgh and subsequent encounters and exchanges, as well as the transcript of the 2006 interview.

Anson came by journalism early in life. His maternal grandfather, Sam Anson, was a prominent Ohio newspaper editor and publisher. Anson himself, Jesuit-educated at St. Ignatius High School in Cleveland, did a stint reporting and writing editorials for the Cleveland Press before enrolling at the University of Notre Dame.

Just out of college, he landed a job as a TIME correspondent, and he moved from the magazine's Chicago office to Los Angeles to its Saigon, Vietnam, bureau in 1969. Multiple careers could have thrived on the list of stories he's covered: the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers, organized crime, the aftermath of the My Lai Massacre, the U.S. defoliation campaign in Vietnam, the "forgotten war" in Laos, coverage of the New Left and anti-war movement on his return to the United States. His assignment in Southeast Asia ended with his capture in Cambodia.

He had a stormy and brief tenure in the 1990s as editor of Los Angeles magazine, authored six books, and in recent years has served as contributing editor for Vanity Fair. A mid-'90s profile described his approach as "reporting without a net," and an Esquire editor described him as "the last of a breed of broad-shouldered, bare-knuckled, '70s magazine journalists who will chopper into any hellhole on Earth and come back with an epic story."

Perhaps it was something among those qualities that convinced Hesburgh, not known for his tolerance of students who brooked his authority or rules, to stick with the student version of Anson.

His first encounter with Hesburgh, Anson writes, occurred Sept. 28, 1963, "to be precise, a non-football Saturday in South Bend, Ind."

"I was a newly-minted freshman then, and Notre Dame was a much different place. There were no women, for starters; Sunday Mass attendance was compulsory; student government recently had come within an eyelash of banning 'The Twist' from campus; and checking out the works of Jean-Paul Sartre and his confreres on the Vatican's Index of Forbidden Books required signed permission from a priest. The university was also overwhelmingly white. In my 958-member class, exactly six were black, and two of them were from Africa."

Anson had been "reared in a most conservative Irish-Catholic household (where nightly prayers were said on behalf of Joe McCarthy) in suburban Cleveland, and exposed to four years of rigorous Jesuit high school instruction to boot."

"Which is not to say that I was a perfect Notre Dame fit. Unlike virtually all of my classmates, my parents were divorced, and from the age of 4, contact with my father was effectively nil. I was also on the decidedly liberal side, particularly on civil rights, and had owned a small black button emblazoned with a white equal sign since the day Ike sent in the troops to Little Rock."

Meeting Hesburgh

The afternoon of Sept. 28, 1963, Anson and a friend hitchhiked to a civil rights demonstration held outside a federal courthouse to protest the killing of four little black girls in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., two weeks before. Hesburgh, a charter member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, was the featured speaker and was being introduced as they arrived.

"The first thing that hit was how much better-looking he was than the portrait of him that appeared on the cover of TIME the previous February -- the one with the slash that asked, 'Where are the Catholic intellectuals?' I remembered that issue very well; it's why I'd decided on Notre Dame, not Holy Cross."

On the way back to campus, Anson and his friend "heard the toot of a car horn behind us. I turned around to see a black Studebaker Lark, Rev. Theodore Martin Hesburgh, CSC, at the wheel. He pulled to the curb and leaned over to roll down the passenger-side window. 'You fellas want a lift?' he asked."

When they arrived at the administration building, "Hesburgh asked if we'd like to come up to his office and chat. I jumped at the opportunity," writes Anson. (His friend had other plans.)

"I spent more than an hour talking with Hesburgh in his office about this, that, and everything. When we were finished, he said, 'Come back whenever you want. Don't call in advance. Just show up any time after midnight. The phone doesn't ring so much then, and I'm usually here until 3:00.'" Anson recalls the two of them had several more long conversations over the course of his years at Notre Dame.

Anson's increasing role as a journalist on campus, engaging in early displays of the swagger for which he would later be celebrated, soon made him a target of the administration.

He first came to the attention of Holy Cross Fr. Charles McCarragher, vice president of student affairs (described by Anson as "Fr. Hesburgh's hard-lining consigliere"), through editorials Anson was delivering on the campus radio station following the evening news.

Anson's highly critical views of Vietnam and Lyndon Johnson apparently didn't sit well with McCarragher. "But his real agitation was over comments on campus doings, especially my drum-banging about the administration's refusal to even consider providing students with professional psychological counseling."

One dorm counselor told Anson that priests filled that role so well "there'd never been a single suicide at Notre Dame. Wouldn't you know, three weeks later, one of my classmates hung himself from his bunk. Not long after that, a junior stepped off the top of the 14-story library."

Anson was invited to join the publication Scholastic as news editor just before Christmas break, 1965. The following semester, the editor chose Anson as his successor for the following year. Previously, the administration's approval of the appointment had been pro forma, but in Anson's case, McCarragher rejected the suggestion and had someone else named.

"I considered making one of my post-midnight visitations to Fr. Hesburgh's office, but decided against it. We'd had several good long talks during the course of the school year, and I didn't want to chance our relationship by bitching about somebody else's call.

"Instead, I retrieved my car from its illegal hide adjacent to the administration building and headed for Chicago, where TIME put me to work covering urban riots, and the open-housing marches of Martin Luther King, including his bloody walk through Chicago's Marquette Park neighborhood. There, late in the afternoon of Aug. 5, 1966, a rock from a howling, racist mob hit him in the head, driving him to the street. A UPI photo of that moment hangs on my office wall. It shows Dr. King bent over, headed down; a young, blonde white man wearing a suit and skinny tie just behind him. The look on my face is impotent horror."

The following semester, Anson helped found a new campus newspaper, The Observer, a tabloid that declared in its first issue, Nov. 3, 1966, that it would be following "a liberal editorial policy."

Anson and The Observer roiled the South Bend waters with the kind of reporting and commentary that its more sedate predecessors avoided. The paper's first major confrontation with the administration, however, was not over politics or campus issues, but over a piece from the Berkeley Barb, a weekly underground newspaper of the era published in California, and used at the last minute on the front page to fill a space when a Notre Dame writer failed to make deadline. The problem: The story was about sex and it used the term "screw."

McCarragher informed Anson that Hesburgh "believed our reprinting the Barb article was 'the most irresponsible act in the history of the university.' His own view, McCarragher said, was that The Observer was 'a prisoner of SDS' [Students for a Democratic Society, a radical left campus movement], and that we were bent on 'destroying the university piece by piece.' "

Anson was given an ultimatum: Print a front-page retraction or face expulsion. Anson bluffed, waited out the threat and the administration ultimately agreed to allow him to distribute an apology letter to the student body in lieu of a front-page retraction.

"Bob had a martyr's complex," Hesburgh told one of his biographers. "People were always asking me, 'Why don't you expel Anson?' I didn't want to give him the satisfaction."

The 15-minute rule

"The whole country, it seemed, was up for grabs," Hesburgh recalled in a 2009 interview with The Observer, "and I thought it was high time that someone set down what the rules of the game were."

He was speaking of his February 1969 edict, dubbed the 15-minute rule, which stated that protesting students were forbidden from disrupting the university or infringing on the rights of others. Those who violated the rule would have 15 minutes to desist or face disciplinary action, including expulsion.

According to news reports, the rule was invoked once, on Nov. 18, 1969, when a throng of students gathered in the administration building to protest student interviews with Dow Chemical Company, which produced napalm, an incendiary gel used in Vietnam, and with the CIA.

Anson learned of these events "via the AP machine in his new office in Saigon, where I'd been posted by TIME two months before."

"Hesburgh, per usual, had done exactly as pledged. It was one of the traits I most admired about him. Not, though, in this instance. Here were good, smart, dedicated kids risking their futures to make a moral point. This was nonviolent, passive resistance right out of the Martin Luther King playbook. How could the chairman of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, of all people, possibly miss that? Who gave a damn if CIA and Dow were inconvenienced for a day? And who allowed them to set up shop literally under the Golden Dome? I stuck a sheet of paper in my typewriter, tapped out a telex address I knew very well, followed by a four-word message. 'You need to resign,' it read.

"I didn't expect a reply, and didn't get one -- though an administration source did convey word that post-midnight drop-ins on the president's office were not advisable for an indefinite while.

"The 'tough, 15-minute rule,' as headline-writers coast-to-coast dubbed it, loosed a chorus of conservative hosannas, including from Richard Nixon, who accompanied his congratulations to Hesburgh with word that Spiro Agnew would soon be seeking his counsel in formulating legislation that would put an end to obstreperous protests once and for all. Hesburgh took the lead heading that off, and for a time calm prevailed."

Cambodia

Anson was next posted to Cambodia, and late the afternoon of Aug. 1, 1970, a mile outside of Skoun, a market town that was a fast, 70-or-so-minute drive from Phnom Penh, he was captured.

"The short of it is that I was at the wheel of a rented Ford Cortina, en route to someplace I shouldn't have been, when elements of the 9th North Vietnamese Division signaled their desire for me to halt with a banana clip of AK-fired full-auto over the roof. Moments later, I was pitched into a shallow foxhole with a trenching tool. Dig deeper, they gestured. I did as ordered, until one of the soldiers screamed something in Vietnamese and yanked the trenching tool back.

"As I closed my eyes and began saying the Hail Mary, I felt a rifle being pressed to my forehead. Then something strange swam into my head, the memory of a French film about the war I'd seen a few weeks before in Singapore. It was called 'Hoa Binh,' the Vietnamese word for peace. 'Hoa binh,' I whimpered. Then louder: 'Hoa binh! Hoa binh!'

"The cold spot on my forehead disappeared, and I opened my eyes to see the soldier who was going to kill me moments before. 'Hoa binh,' he said, as if testing he'd heard me correctly. 'Hoa binh,' I repeated. 'Hoa binh.' He nodded, then, with surprising gentleness, reached down and pulled me out of the hole."

His captors held him for about a month.

"The English-speaking officer who told me I was being released said it was because I'd saved the lives of some Vietnamese children, who'd been badly wounded during a massacre by Cambodian troops at a place called Takeo.

"The incident, which was splashed across the front page of The New York Times, put a permanent end to mass murders of Vietnamese civilians, thousands of whom had been butchered in the aftermath of Lon Nol's coup. But I still had questions, starting with how my captors had learned about Takeo. I hadn't told them, the Vietnamese officer wouldn't say, and it seemed unlikely they subscribed to The New York Times. So who was my guardian angel?

"Fifteen years would slip by before I'd have the answer. One thing I did learn as soon as I got to the TIME bureau in Saigon was that Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, had moved heaven and earth trying to save my life. Not figuratively, literally."

Anson learned that Hesburgh later described the request as comparable to "being asked to get the devil out of hell." He received the request from a TIME editor who told him he was their only chance to get Anson freed. So Hesburgh put in a call to Pope Paul VI, who reportedly was able to intervene with Cambodian authorities and helped arrange Anson's release.

1974 campus rape story

If Anson was grateful for Hesburgh's role in ending his captivity, it didn't stop him from diving into a controversial story four years later. His account follows:

In late July 1974, I chanced on an AP story reporting that Notre Dame had suspended six members of the football team "for at least one year," following an accusation by an unnamed 18-year-old South Bend girl that they'd gang-raped her in a university dorm.

Apart from the fact that all the players denied the allegation, and that criminal charges had yet to be brought against any of them -- and didn't seem likely, given the he-said, she-said nature of the case -- details of the incident were sketchy. This struck me as odd. Even a hint of scandal involving Notre Dame's football team, which had defeated Alabama for the National Championship the previous New Years -- was hot news ordinarily. There was also a racial angle: the accused were black, their accuser white. Nonetheless, the story was buried deep in the sports columns, and the leading media outlets were ignoring it altogether.

My wonderment increased as I ferreted out additional details. For one, virtually all of the principals -- including the county prosecutor, the young woman's attorney and the South Bend Tribune reporter on the story -- were Notre Dame graduates. For another, Notre Dame spokesmen weren't saying boo, save that the accused players had been suspended for "a serious violation of university regulations."

The implication was that the penalty had been imposed by the university official tasked with investigating the case, Dean of Students John Macheca. Turned out, though, that Macheca, a former National Security Agency intelligence analyst who'd resigned over Vietnam, had wanted the players expelled. But in the interests of "compassion," he'd been overridden by Fr. Hesburgh.

Meanwhile, Coach Ara Parseghian was attributing the loss of four projected starters and two key backups to the decline of female morality brought on by watching soap operas. As for the alleged victim, a university administrator told me, "You know the type. A queen of the slums with a mattress tied to her back."

There was plenty that didn't smell right. New Times, a well-regarded investigative biweekly and my then-employer, agreed, and I hopped a flight to South Bend.

I'd worried en route about getting key medical and law enforcement sources to open up. All you had to do, it developed, was ask. I learned a lot with this tactic, including that the prosecutor's office had looked into the young woman's background and found it spotless, and that medical personnel who'd treated her immediately after the incident had no doubt that she'd been sexually assaulted, or that the trauma caused required several weeks psychiatric hospitalization.

I also managed to secure the young woman's name, home address and telephone number. She wasn't available, but her parents were. I debated calling, decided against it, and one midevening simply drove out to the house, a meticulously kept suburban split-level miles from the nearest slum.

I rang the bell, and a middle-aged man with the physique of a onetime tight end -- an engineer at Bendix, I was subsequently informed -- opened the door. I hadn't planned what to say; the words just tumbled out: "I'm a reporter from New York. There are 7,000 men at the university who think your daughter's a whore, and I don't believe it."

His face reddened and fists balled. I thought he was going to slug me. Then tears welled in his eyes. "I need to talk to my wife," he said.

He opened the door 20 minutes or so later, invited me in. His wife joined us and we sat down in the living room. There was a moment's awkward silence. Finally, I said, "Just tell me what you think I need to know."

By the time we finished it was nearly 11:00. All that remained was getting the other side of the story. I picked up the phone in the Morris Inn room where I was staying and dialed a number I knew by heart. Fr. Hesburgh was not pleased to hear from me.

"We're going to sue you, and we're going to get big damages," he said, after I'd given him the highlights. "If need be, we can produce dozens of eyewitnesses."

I resisted inquiring how "dozens" could "eyewitness" an event that supposedly never took place. Instead, I said, "Father, the parents told me that no one from the university ever contacted their daughter."

"I didn't have to talk to the girl," Hesburgh said. "I talked to the boys."

At which point, I hung up.

Anson wrote the story, including quotes from Hesburgh. "Notre Dame never sued, and no eyewitness ever came forward. But it was years before Fr. Hesburgh and I talked again. We stayed in indirect touch, though, via friendly messages passed back and forth by our close mutual friend, William C. Friday, president emeritus of the University of North Carolina."

The interview

In 2006, Anson took the elevator one last time to the 13th floor of the Theodore M. Hesburgh Memorial Library.

"Its namesake could not have been nicer," Anson recalled. "From the moment he shook my hand and took my shoulder in greeting, to when I most reluctantly said goodbye an hour later, our time together was like being in a warm bath. I knew that I'd missed him, but it wasn't until that moment that I realized how much.

"Except for the hair that had gone white, and the jowls and girth that had enlarged a tad, he looked, sounded and acted like the man who'd stopped to offer a lift on a sunny Saturday afternoon in September 1963."

The conversation ranged freely from the personal to the global and included a considerable amount of political recollection.

The topic of immigration came up early in the conversation and Hesburgh told of a plan that he and "good friend" former Sen. Alan Simpson, a conservative Republican from Wyoming, and liberal Democratic Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts put together to solve the immigration problem. They wanted to institute a European-style ID card that would be given to all, including undocumented immigrants, which Hesburgh thought would eliminate the need for all "the cops and robbers" at the border. If people had the ID, they could work; if not, they would be unable to obtain work and would eventually return home. But the American Civil Liberties Union objected to it and killed the idea, he said.

Anson raised a personal matter.

Anson: You know, believe it or not, I have been meaning -- literally for the last at least 10 years, I've started it and stopped it a number of times -- to write you a letter to say that for all the tsuris we have been through, you have had the most profound influence on my life than anybody.

Hesburgh: Well, I feel responsible for you, Robert, because you wouldn't be sitting here if we both hadn't listened.

Anson: I read Henry Grunwald's memoirs. [Grunwald as managing editor of TIME when Anson was a correspondent in Indochina and later]. He quoted you as saying that I was the "most difficult student" you'd ever had. I didn't know whether to be flattered or not. But I was thinking about that, and wondering the reasons for it. I mean, apart from the fact that I was just a jerk with you a fair amount of the time.

Hesburgh: Well, you know, you were a student editor. All student editors are trouble; I take that as a given.

Anson: Well, I sure was trouble.

Hesburgh: Goes with the territory. You came out one day and wrote, "Best thing Father Ted could do is resign." That was a headline. I still remember it.

Anson: Did I really do that? Okay.

Hesburgh: A pretty strong headline.

Anson: I must have done a very convenient memory erase about that one. I'll take a look at it. I wondered, 'cause politically we're pretty much alike.

Hesburgh: I think so.

Anson: I just wondered if it was almost generational, over Vietnam.

Hesburgh: I think it was. That was a terrible period for young people. One, you had Vietnam, you had civil rights coming to a boil, you had the whole resurgence of civil rights work in the South. Constant trouble every day, every day. But in the long run, I think it was a very interesting period in American history and we won. And justice won. And today we, you know, you said what civil rights laws do we need today? We really don't. Now it's a question of observance and monitoring. The laws are all in the books.

Anson concludes his recollection:

I came back to Notre Dame twice in the years that followed, once for the 40th anniversary of The Observer, and six months later, for my 40th class reunion. But we never connected.

I missed him, wrote him a letter saying so and apologizing for being the source of so many headaches as a student and since. I said I was sorry most for failing to ask for his blessing when we'd seen each other. Father wrote back: "It's now 4:30 in the afternoon. Consider yourself blessed."

Was I ever, in so many ways.