God creates Adam in a ceiling fresco painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican (Wikimedia Commons/Jörg Bittner Unna, CC-3.0)

How many contemporary Christians consider Adam and Eve as real persons, the first man and woman created by God, our first parents from whom we have all descended? The first two chapters of Genesis and the stories that follow are the work of four different traditions of scholars who, in the sixth century B.C., have just been released from decades of captivity in Babylon and are struggling to fill the historical void. Israel had not had a collective sacred text in a thousand years.

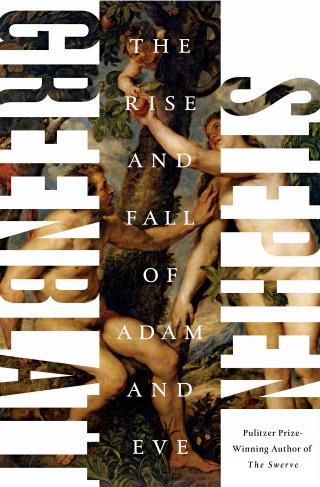

Stephen Greenblatt, author of The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve, a Harvard University professor of humanities, has dug far into the otherwise undocumented past and the folk Epic of Gilgamesh, perhaps the oldest story ever found, for a flood story that would feed the Genesis Noah flood.

He introduces the reader to Augustine, Pelagius, John Milton, Voltaire and Charles Darwin, along with classic artists who present their naked subjects with their sexual organs either smothered with the fig leaves of shame or proudly exposed as evidence of their purity and honor.

About 30 paintings in the book include Albrecht Dürer, who expresses his own fascination with Adam's body by a detailed naked self portrait (1505); Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel, which features God reaching out to touch the fingertip of the nude Adam (1508-12); and Masaccio, who offers two portraits of Adam and Eve's "Expulsion from the Garden of Eden," one with fig leaves and one without.

Augustine explained his own sinfulness by connecting it to the sin of Adam, his "first father." Remembering his childhood sins, he said, "Our real pleasure consisted in doing something that was forbidden." On the other hand, a British-born monk named Pelagius and his followers believed men were born innocent and free to shape their own lives. We have free will.

While Pelagius agreed that the experience of sexual intercourse was natural, Augustine insisted that sexual intercourse between husband and wife is corrupt, even if they conceive a child. Because of the pleasure in sexual arousal, Augustine believed, we have only partially freed ourselves from original sin.

Masaccio's "Expulsion from the Garden of Eden" (circa 1425) (Wikimedia Commons/Paolo Villa, CC-4.0)

John Milton became known both as a poet and a critic of the Episcopal hierarchy. He had also committed himself to a life of chastity, avoiding sexual intercourse until he was married. But when he turned 33, he found himself very lonely, until he traveled to Forest Hill and met Mary Powell, only 17 and of a Royalist family. Their marriage lasted about a month. Mary returned home, where she had lots of fun and friends, which she did not have while married to Milton.

Milton wanted to marry again, but church law did not grant him an annulment. He discovered in Genesis that God created Eve because, "It is not good that man should be alone." The principal purpose of marriage, Milton argued, is neither sex nor children; it is companionship.

Three years later, Mary's family lost their social standing when Oliver Cromwell won the English Civil War. What would happen to Mary? One summer day when Milton was visiting a relative, Mary appeared, fell to her knees and begged for his pardon. She gave birth to three girls and one boy in six years and died in 1652.

Milton's eyesight gone and his later wives dead, he withdrew into his imagination and every night received a visit from a "celestial patroness" who guided his dreams. Then at dawn he would read the Hebrew Bible and dictate an epic poem to a secretary. His masterpiece about Adam and Eve, Paradise Lost, was published in 1667.

In the following generations, belief in the literal interpretation of the creation story began to die out. Images of real people in unreal circumstances — a talking snake, God walking in the evening breeze, and the terrible punishments for minor offenses — led more people to accept immediate experience as reality.

French philosopher Pierre Bayle, in A Historical and Critical Dictionary (1697), dealt with the problem of evil in a footnote. He wrote, "The best answer that can be naturally returned to the question, 'Why did God permit that man should sin?' is this, 'I don't know.' " It became a bestseller, though it failed to win believers.

In the United States, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau dreamed of getting out of time and meeting Adam on a nature walk. In Leaves of Grass, Whitman would say to Adam, "Touch me, touch the palm of your hand to my body as I pass / Be not afraid of my body."

Advertisement

Mark Twain, in The Innocents Abroad, visited Jerusalem's Church of the Holy Sepulcher and was moved to tears at the alleged tomb of Adam. He felt he had discovered the grave of a blood relation.

"Darwinism is not incompatible with belief in God, but it is certainly incompatible with belief in Adam and Eve," writes Greenblatt. Darwin's critics called him the "Monkey Man" for besmirching our ancestry, but Darwin replied that he would rather be descended from a heroic little monkey or an old baboon who had carried a young comrade down a mountain than from a savage who tortures enemies and practices infanticide.

Greenblatt concludes that the naked man and woman in the garden "remain a powerful, even indispensable, way to think about innocence, temptation, and moral choice, about cleaving to a beloved partner, about work and sex and death."

I wish he had heard about Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the 20th-century French Jesuit paleontologist who has a theory of cosmic life ascending through humanity toward an ultimate Omega Point to Jesus Christ. I also wish he had heard of the Dutch theologian Edward Schillebeeckx, who placed original sin in the crucifixion of Jesus, in the violence beginning when Cain killed Abel; this poisoned the moral universe leading to the murder of Jesus and every violent act since his death.

Meanwhile, Greenblatt concludes, Adam and Eve "have the life — the peculiar, intense, magical reality — of literature."

[Jesuit Fr. Raymond Schroth is editor emeritus at America magazine and a full-time writer living at Fordham University.]