(Unsplash/Jessica Ruscello)

At the Trying to Say God conference this past June, more than 200 Catholic writers traveled to the University of Notre Dame to grapple with the question that has generated thousands of words of analysis in the past few years: Is Catholic literature dead? No single answer arrived, but in the panels I spoke on and attended, a more complicated and arguably more interesting question generated the most discussion: Have writers lost what Andrew Greeley referred to as a "Catholic imagination"?

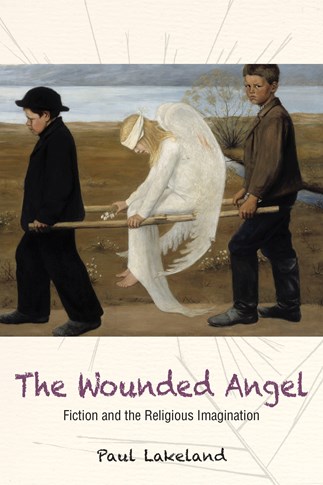

Paul Lakeland's book The Wounded Angel: Fiction and the Religious Imagination, is an attempt to answer the latter question by merging theology with literary criticism. It is also an answer to an ongoing debate about the role literature should play in an increasingly secularized America.

In 2012, literary critic Paul Elie wrote an essay for The New York Times asking if fiction had lost its faith and arguing that he was, as he put it in a later blog post, "holding out for the phenomenal" in writing by Catholics in particular. A year later, Dana Gioia's 2013 essay in First Things, "The Catholic Writer Today," stated that Catholic writers are "isolated, alienated, discredited, ignored." Elie and Gioia both agreed that there needed to be a more robust Catholic literary culture in America, but gave very few suggestions as to how one could be nurtured or supported.

But Gregory Wolfe, the editor of Image journal, which publishes ecumenical literature about spirituality and religion, said in an essay titled "The Catholic Writer: Then and Now" that the problem isn't an anti-Catholic literary culture or a lack of "phenomenal" writing about faith but that "ideological blinders have prevented religious and secular people alike from perceiving and engaging the work that is out there."

The Notre Dame conference was put together to help promote contemporary Catholic writing, and to provide room to discuss the fact that many writers who produce it are not working in tenured lines in academia or getting published by large New York publishing houses but instead are adjunct teaching, blogging, writing for small magazines, or running small presses.

The writers gathered at the conference share Greely's notion of a "Catholic imagination," whether they write poetry, fiction or nonfiction. Their world, as Gerard Manley Hopkins would put it, is "charged with the grandeur of God." But who is reading what they write?

Advertisement

Lakeland's book is less concerned with providing examples of contemporary writers grappling with the question of Catholic imagination than he is with grappling with imagination itself. Fiction, he argues, is a particularly significant genre because it exercises the reader's own imagination and because it can require what he refers to as "serious reading."

Fiction, he writes, "supports love of the world as it is and contradicts the simplistic separation of the sacred and profane."

Lakeland spends a good chunk of The Wounded Angel acknowledging that we are heading into what looks like a post-religious culture in America, one that is less interested in questions of faith in its fiction and more interested in entertainment and distraction. Faith, he writes, "has become an individual decision," and so has what we read.

Literature, Lakeland acknowledges, is often about seeking pleasure: If reading fiction is an imaginative act, reading is therefore pleasurable for those with active imaginations.

But religion, he acknowledges, also requires a sense of imagination. Think of the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, where believers imagine themselves into Bible scenes alongside Jesus. However, in a time when religious practice is about making choices, many of those choices have been stripped of imagination. Religion, at least in America, is so politicized that it has almost no imagination left.

One can understand why "serious reading" of religious fiction like that of Fyodor Dostoyevsky or Marilynne Robinson, both of whom are mentioned in Lakeland's book, is a discipline our battered attention spans cannot always manage. Lakeland also compares reading to an act of faith, both of which require sustained discipline that many readers and believers alike lack.

People read less fiction today, not only because they don't have time for it, but also because the horrors of the world can be so overwhelming that our imaginations are increasingly apocalyptic and dystopian rather than faith-based, which would theoretically always end with a narrative of redemption. Religion's greatest temptation, Lakeland writes, is to "mediate, if not even control, the experience of the holy itself."

But that is also the role of the novelist, who not only has control over the lives of her characters, but also holds emotional control over her readers. Readers who are emotionally overwhelmed might understandably instead turn to nonfiction, which has spiked in popularity in the last decade, in order to grapple with reality, learn history or delve deeper into social issues.

Religion's greatest temptation, author Paul Lakeland writes, is to "mediate, if not even control, the experience of the holy itself."

Or they might choose poetry, which offers us the opportunity to be stunned by language rather than plot devices, monologues or the internal thoughts of a fictitious narrator.

Given these choices about what we read, why is fiction important, especially today? Lakeland's book returns toward its end to the idea of the Catholic imagination, which is ultimately a sacramental one. Fiction can offer a world infused by grace in a manner that nonfiction and poetry might struggle to get across. The problem of good and evil, too, is perhaps better understood through the lens of a novel than through the morally muddled realities of our world.

Fiction, Lakeland points out near the end of the book, is accessible, requires careful consideration and approaches the mystery of the holy through the framework of storytelling. If it is a form of escape, under Lakeland's tutelage that escape can be more akin to a religious retreat than a beach vacation. We need both, but one might nurture us more than the other. Thankfully, there are enough books for us to decide what form that nurturing might take.

[Kaya Oakes is the author of four books, including The Nones Are Alright: A New Generation of Believers, Seekers, and Those in Between. She teaches nonfiction writing at the University of California, Berkeley.]