Unsplash/John Price

Czeslaw Milosz did not consider himself to be a Catholic poet. But in his later years, he noted that all of his thinking had a religious aspect, and in that sense, he said, his poetry was also religious.

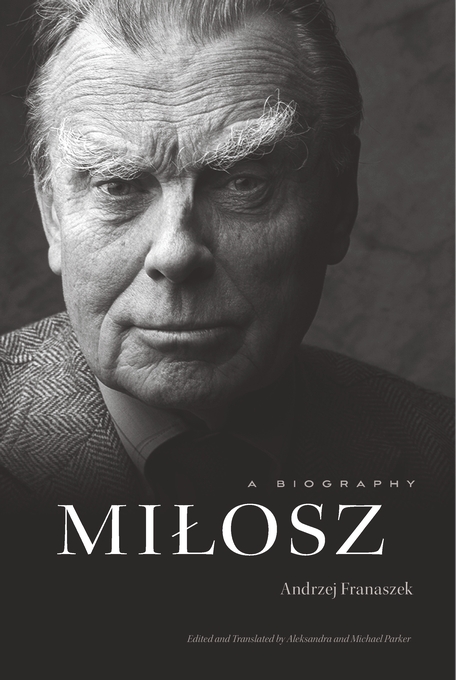

Milosz, A Biography by Andrzej Franaszek examines Milosz's religious sensibilities as they appear in his life and writing. The text (translated by Aleksandra and Michael Parker from the longer Polish version that came out in 2011) is replete with excerpts from Milosz's poems, letters, interviews and photographs and includes an extensive bibliography and a chronology of Milosz's life with a list of contemporaneous political and historical events.

The book begins with the poet's birth in 1911 on his grandparents' estate and ends in 2004 with his death in Krakow. Though Milosz was born in a little known Lithuanian town of Seteiniai, he considered himself to be a Polish author because his family spoke Polish. According to Franaszek's account, however, the author's spiritual mindset was more Lithuanian than Polish.

Milosz's poems suggest that he leaned towards Lithuania's mix of magic, pantheism and Christian mysticism. He was especially close to his maternal grandmother, Jozefa, who spent hours in prayer. Milosz later learned that her piety was blended with superstition.

Writing his first poem at 13, he published approximately 25 books, ending with About Journeys Through Time, a book of essays. Three other books were issued posthumously, including New and Collected Poems: 1931-2001, which was reprinted in April 2017.

Milosz was highly regarded for his many prose works, such as his autobiographical novel, The Issa Valley, his spiritual biography, The Land of Ulro, his reflections on literature, The Witness of Poetry, and his collection of essays refuting totalitarianism, The Captive Mind, which, he said, originated in a prayer.

Milosz wrote prose and poems about the devastation he experienced during invasions by Czarist and Soviet Russia as well as by Poland and Germany. He lived through both world wars, and afterward, his homeland was carved up and given over to the Soviets. Then, in the 1990s, he witnessed the rise of the Solidarity Movement and the fall of the Soviet Union.

Through it all, he was sustained by his wife, brother, friends and faith. As Franaszek quotes from one of Milosz's essays: "Had it not been for the Catholic faith and [being] able to pray in adulthood, I would have perished. … I believed that I have a place in God's agenda, and I asked for the ability to fulfill the tasks awaiting me."

Milosz was friends with luminaries like Thomas Merton and Pope John Paul II, the latter of whom corresponded with him. Another friend, Lech Walesa, said that Milosz's poems inspired the Solidarity Movement. Ultimately, Milosz won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980 for clearly expressing "man's exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts."

Advertisement

Milosz spent several years in Warsaw and Paris where he worked in broadcasting before coming to the U.S. to work in the diplomatic corps. He went back to Europe, then came to California to teach Polish literature at the University of California, Berkeley. Eventually, he came to see Americans as a shallow and materialistic people and returned to Krakow in 1993 where he died 11 years later.

Franaszek adds many details to his biography, a move which slows the book's pace. He quotes from Milosz's discussions of various things like the birch forests of Lithuania; his love for his mother, his uncle Oskar Milosz, a poet and mystic living in Paris; his son's mental illness; his own bouts with depression; his disdain for Communism; and his philosophical and religious beliefs.

Milosz disliked the Polish Catholic Church's clericalism and sense of religiosity as well as its prejudice against minority groups. He also thought the Polish church saw faith as something to be exhibited, as opposed to "an energizing moral force."

Milosz quarreled with Catholicism. As a teenager, he questioned confession. Later he doubted the resurrection of the body. But overall, he believed in its tenets. "I ought to be asked whether I believe that the four Gospels are truthful. My answer to this is 'yes.' Do I believe the absurdity that Jesus rose from the dead? My answer is 'yes,' and so I refute the omnipotence of death."

Milosz's friend, Fr. Jozef Sadzik, a scholar and a patron of the arts, wrote the introduction to The Land of Ulro. Sadzik encouraged Milosz to translate books from the Bible into Polish. Milosz later said that the exercise helped his depression.

According to Franaszek, Milosz often confided in Sadzik, telling him "that Catholicism lay at the core of his thinking and his poetry, which continued to retain an apocalyptic dimension."

And as suggested in this compelling, well-written biography, it's that dimension — along with his religious beliefs — that has given Milosz's work its staying power.

[Diane Scharper is a poet of Lithuanian descent and the author of several books, including Radiant, Prayer Poems (Cathedral Foundation Press).]