(Unsplash/The Good Funeral Guide)

My wife Vickie died eight months ago. At first, the sense of her presence was as palpable as my heartbeat. She was in heaven, sure, but she was also here, there, everywhere. That awareness lasted a week. Then it faded. I felt dull and rarely left the apartment.

Grief is more than missing someone. It's the thought that you have lost someone or something essential to what you are here for.

I didn't want to do anything. I forced myself to do the basics. I made my bed right away, shaved and got dressed. I ate cereal with strawberries and read The New York Times with a cup of Folgers coffee, just like always. Then … I didn't know what to do. I was still asleep and couldn't wake up.

Grief is a snake that you deny is slithering around your spine, paralyzing you. You don't want to believe it. After all, wasn't I grieving for 20 years as I watched my best friend slowly disappear in the grip of Alzheimer's? Wasn't that enough?

Grief is being in a movie and watching your leading lady walk off the screen. You don't know what your role in the movie is any more.

Vickie and I used to love to go to the movies in the early afternoon, when few — if any — people were there. We would share a bowl of hot buttered popcorn and an iced Coke sipped through the same straw. But soon Vickie could no longer keep track of the plot of the picture or the storyline of her own life. I'd let her know what was happening. "Shhh," she'd say, "I'm watching a movie."

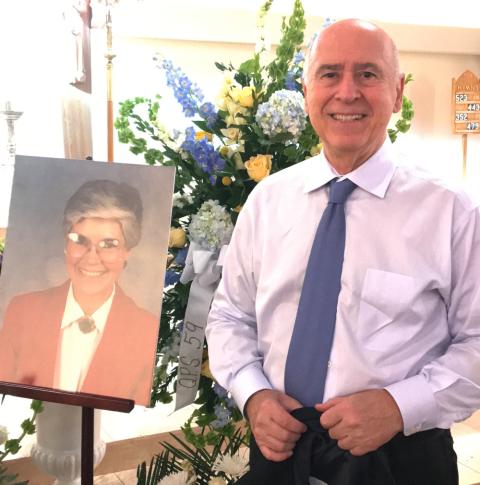

Mike Leach with a photo of his wife Vickie at the Nov. 5, 2022, memorial service at Our Lady Star of the Sea Church in Stamford, Connecticut. (Courtesy of Mike Leach)

The days after her death on Oct. 27, 2022, when her presence was still as real as the vivid colors of the season, I wrote about how she had let me know she would always be with me, and that love wanted me to keep on living. I haven't written anything since. I didn't know what to write. Even now, the words come out of my fingertips in slivers.

I have pretended to be OK. Why drag others into my dreary movie? "How are you doing?" they ask. "Fine," I say. If I say that often enough, maybe it will be so. What did Zooey Glass say to his actress sister Franny when she was so depressed, she couldn't get out of bed? "The only thing you can do now, the only religious thing you can do, is act. Act for God, if you want to — be God's actress if you want to. What could be prettier?"

That's me. The actor.

My heart tells me it's time to change the reel. It's time to get real again, and plead to God that I need his grace to wake up. It isn't easy to wake up when a movie puts you to sleep. I can't snap out of it like Nicolas Cage in "Moonstruck" when Cher slapped him in the face. I don't want a slap. I want a kiss.

I know if I close my eyes and ask God sincerely, no holds barred, to tell me what I need to know to be awake, God will. I haven't done that in eight months. I will now. Hold on …

God answered me: "You can't do this for a column you're writing."

OK then. How do I escape the blues? American philosopher Cornel West describes the blues as a song of despair that is not despair. It is "a naming of the pain." It is singing, "I can't go on. I will go on. I can't go on. I will go on." West is paraphrasing a line from Waiting for Godot.

I am waiting for God. I know it. I sing the blues but am lost, yearning for a way back home, to peace, assurance. I don't want to just "go on." I want to be like the prodigal son and climb out of the ditch and return home. I want my father to rush out of the house before I'm half way there and throw his arms around me and give me a kiss and make me a feast. "Son," he'll say, "In my eyes you never left me!"

I can't scratch my way out the ditch with my fingernails. I need God to raise me up on eagles' wings. I need a Good Samaritan to stop by the side of the road and bind my wound and carry me home. I can't wake up alone.

I am waiting for God. I know it. I sing the blues but am lost, yearning for a way back home, to peace, assurance. I don't want to just "go on."

Cencia, the caregiver from heaven via Haiti, stops by the apartment on Fridays after picking up Roobens from day care. Vickie had asked her to make sure I'd be alright. She asked me to make sure Cencia would be alright. Cencia's goodness makes my burden light.

Cencia and Vickie were BFFs. She cleaned, clothed, fed and talked with Vickie as if Vickie were perfectly alright, and both of us held one of Vickie's hands as the three of us watched "Ted Lasso" cheer everyone up.

Four-year-old Roobens and I are buds. We play soldiers with the rubber Disney characters — Mickey and Minnie, Donald and Goofy — that my grand twins used to splash around with in the tub. Some Sunday afternoons, I take Cencia and Roobens and his big sisters Tanisha and Naomi down to the pool. Cencia puts water wings on Roobens and I pull him around the shallow water and teach him how to float. Cencia sits on the edge of a folding chair and holds a towel, like Veronica with her veil.

One Wednesday a month, I have lunch with two of my friends from our support group for husbands with wives who have Alzheimer's. We're widowers now. Len is a mensch and Gary is as sweet as the good fruit on the biblical fig tree. I always get scrambled eggs with bacon. Len gets a turkey club, and Gary studies the menu while we bust him. I used to think that only old friends could be best friends but that isn't true. We are Simon of Cyrene to each other.

Yesterday afternoon, my old friend Jon was celebrating his 80th birthday with a flock of friends from everywhere. I didn't want to go. I didn't want to pretend to have fun with people I didn't know. I didn't want to disappoint Jon either. I put good clothes on at the last minute. On the way out, I hesitated at Vickie's picture on the mantle. "I don't want to go, sweetheart, it's too far to drive." Her voice whispered within me, like the voice that told Joseph to take Mary and Jesus to an unknown country. "You have to go," she said. "It will be good for you."

Was she never wrong?

A spark of life ignited my soul at a birthday party I didn't want to attend. I took that spark home and fanned it like the contestants do on "Survivor," with the dry grass of my grief, the tinder of my joyful memories and the oxygen of connection with friends old and new. I'm still grieving, still in the movie, but as the late Rabbi Earl Grollman wrote, "Grief is the price you pay for love. The only cure for grief is to grieve."

Experts say the grieving process can last from six months to four years. The greatest of them, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, said:

The reality is that you will grieve forever. You will not 'get over' the loss of a loved one; you'll learn to live with it. You will heal and you will rebuild yourself around the loss you have suffered. You will be whole again but you will never be the same. Nor should you be the same, nor would you want to.

I'm sharing all this with you, my readers, because I love you and know that many of you, too, are grieving or suffering from unresolved grief. I hold your hand at the crossroad of hope and despair. We will wake up together. It's alright. Your feelings are alright. Everything is going to be alright.