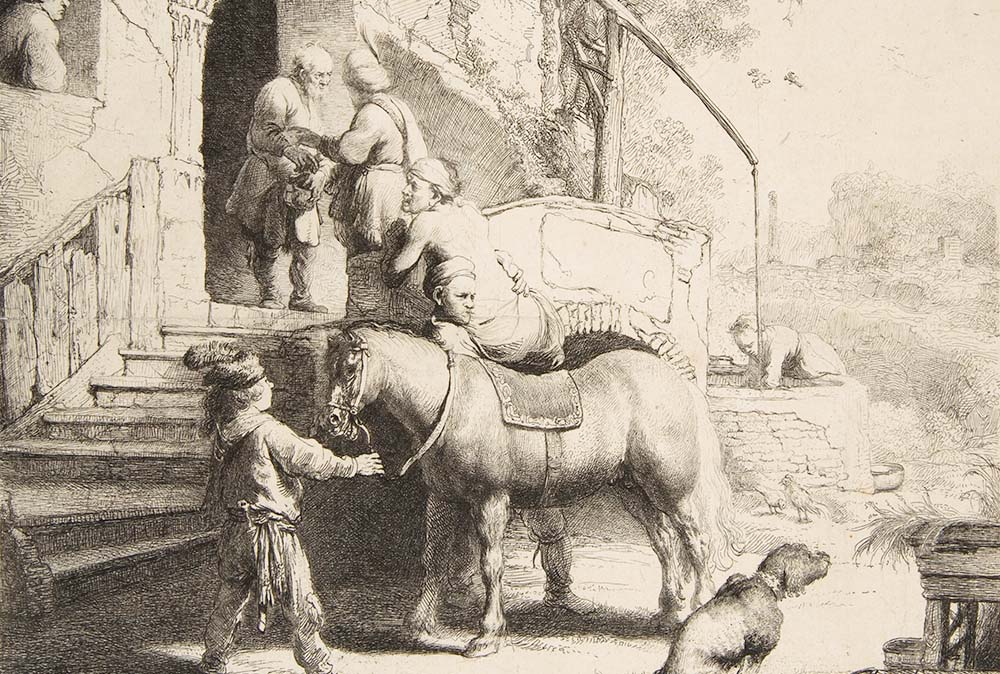

"The Good Samaritan," detail from a 1633 etching by Rembrandt (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

What does God look like? Kids ask that with equal measures of innocence and expectation. What a disappointment to hear that God is invisible! If we ask Google, we get a wide variety of images: mostly white beards and triangles, traditional and modern pictures of Jesus and, it's no surprise, almost no feminine figures.

In the hymn he placed in the letter to the Colossians, Paul portrays Christ as the image of the invisible God. This hymn reminds us of Teilhard de Chardin, who envisioned Christ as the origin and destiny of the universe, the God who took flesh and the human who assumed divinity, the one through whom all creation came to be and in whom all will be united. Paul and Teilhard are brother mystics inspiring us to wonder. Following their lead, we could spend a lifetime taking it in and letting it transform our inner selves.

On days when we need a story rather than poetry, we can turn to the first three Gospels. Today, Luke narrates one of Jesus' most well-known parables, one that never ceases to challenge us. It calls us to look anew at the maligned Samaritans of our day.

Jesus' challenge becomes knife-sharp if we let the Samaritan represent not only marginated people, but especially the people with whom we disagree most vehemently. Can you imagine what it would have felt like to be desperate and rescued by one of "that kind"? Needing the person we denigrate is the most uncomfortable image in the story.

When we picture ourselves in the scenario, we might have a bit more sympathy for those who passed by. We've all heard stories of entrapment in which someone fakes a need only to ambush (or find a way to sue) the helper. Anyone traveling alone would be prudent to avoid such a potential snare.

Instead of taking heed, our good Samaritan freely offered his service and his goods to replace what had been stolen from the victim.

We know all of that. Now, suppose we listen to the parable as a response to the question we started with. What if we listened as if Jesus were using this parable not just to describe who is a neighbor, but to draw a portrait of God? A self-portrait? What would it mean to envision God as the Samaritan?

Seeing the victim's plight, the Samaritan dropped his plans, sacrificed his own provisions to treat the other's wounds, transformed his cargo animal into an ambulance and finally commissioned someone else to continue caring for the victim. Who better than this Samaritan gives us a portrait of Christ, the compassionate incarnate Word of God?

From this vantage point, we have a story about someone whose human dignity has been defaced in every possible way: robbed of possessions, denuded and left for dead. Responding to this victim inevitably entails a risk. On one hand, there is the risk of ambush, turning the would-be helper into the real victim. On the other hand, the helper's move toward the victim inevitably implies putting all he is and has at the service of the other.

In either case, the helper freely assumes the vulnerability of the victim.

Advertisement

Is there any story in the Christian Scriptures that offers a more poignant depiction of Christ's mission? The Nativity tells us that God took on our vulnerability and the Passion shows us that the Incarnation led to Jesus' victimization by the very ones he wanted to save. Here, in the middle of Luke's Gospel, we get the parable that explains the motive of Jesus' mission. When God sees suffering and need, the divine response is intimate, unbounded solidarity.

When Luke describes the Samaritan's compassion, he uses the word splanchnizomai, which refers to being moved in your womb or guts. This portrays God in Christ as passionate for the well-being of creation. This tells us that God honestly assumes the pain of every person who suffers and bears the cost of their suffering.

The work of the Samaritan, the being moved, binding the wounds, carrying the victim and commissioning his care describes God's response to the world's need. It tells us that God looks like an eternal first responder.

It harks back to the day that Moses heard God say, "I have witnessed the affliction of my people, I know well what they are suffering, therefore I have come down" (Exodus 3:7-8). The parable of the good Samaritan tells us that God wears many faces, faces that are visible wherever human beings risk solidarity with others who suffer.

What is the message for us? Nothing more or less than Jesus' conclusion to this story. Looking at the poor and all innocent victims, he addresses us, saying: "Go and do likewise."

[St. Joseph Sr. Mary M. McGlone serves on the congregational leadership team of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet.]