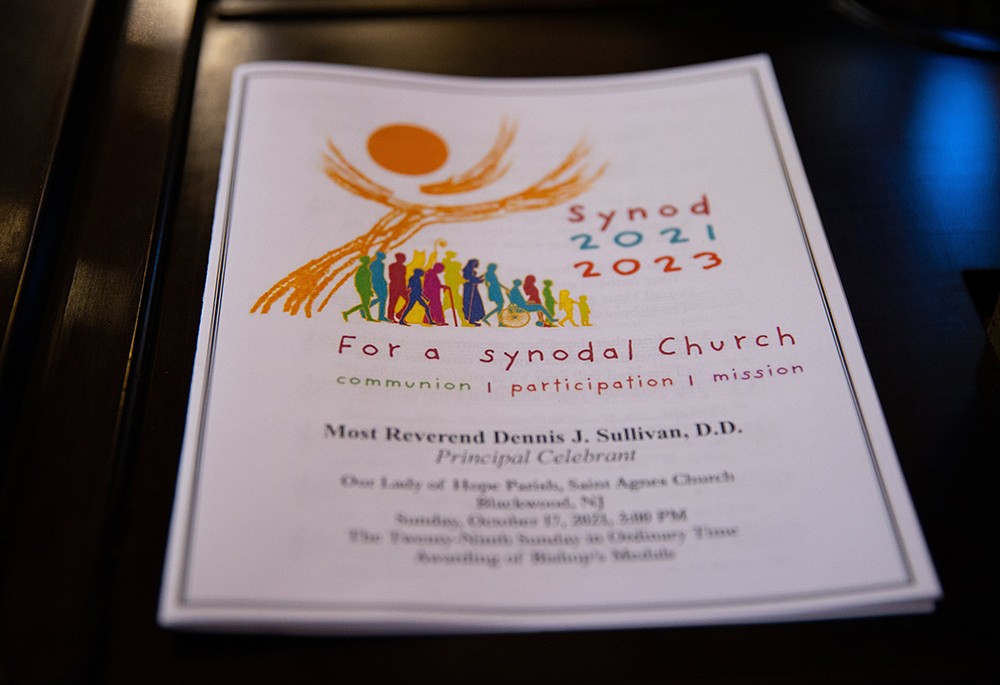

A program for a Mass opening the synod process in the Diocese of Camden, New Jersey, is seen at St. Agnes Church of Our Lady of Hope Parish Oct. 17, 2021, in Blackwood. Over several months reflections were collected from the faithful in parishes across the diocese and put before diocesan teams and deaneries as part of the churchwide preparation process for the 2023 world Synod of Bishops on synodality. (CNS/Catholic Star Herald/Dave Hernandez)

The U.S. bishops' conference issued its "National Synthesis of the People of God in the United States of America for the Diocesan Phase of the 2021-2023 Synod." The document is exceedingly well done, bringing together into one, concise and readable document the results of 22,000 reports from 30,000 listening sessions, in which the conference estimates some 700,000 people participated. Those numbers are staggering, a rebuke to the naysayers who viewed this process with suspicion.

Others have reported on the contents of the report, such as Dennis Sadowski for Catholic News Service's fine summation. I do not suppose anyone was surprised about the issues that arose nationwide: the desire for a more welcoming church, concern about the role of women and the laity, a desire to overcome the divisiveness of society or at least keep it from infiltrating the church, etc. It was refreshing to see a document produced by the bishops' conference acknowledge "the perceived lack of unity among the bishops in the United States, and even of some individual bishops with the Holy Father, [is] a source of grave scandal."

So, kudos to everyone who participated in this enormous undertaking and to the staff at the bishops' conference who brought it all together.

Now what? That is the question that hangs over the text. Do we wait around until the synodal gathering in Rome in the autumn of 2023? Won't all this positive energy dissipate if we just stand around and watch the wallpaper age? In short, setting aside specific issues, how does the process continue?

The synthesis acknowledges the challenge. In the section on discernment, it states: "The next step for the U.S. Church is to give special attention to its parishes and dioceses, even as we continue participation in the continental and universal phases of the Synod, for that is where the People of God most concretely encounter the Spirit at work and where the first fruits of this discernment will be realized."

Advertisement

The text includes some hints about what such discernment will look like. It states, "Discernment attends to the voice of the Lord in the Church's liturgy, in the Church's teaching tradition, and in the voice of the lived experience of the People of God."

If I were planning a priest convocation for this winter, the topic would be: How do these three sources of inspiration interact? Teasing that out is not easy, especially at a time when, as Boston College Professor Cathleen Kaveny likes to say, "Every guy with a copy of the catechism, an internet connection and an attitude thinks he's a theologian."

Quoting from the report of Region 9, which encompasses the provinces of Omaha and Kansas City, Kansas, about welcoming people without judging:

Whole groups of people feel that the teachings of the church preclude their sense of being welcome in the community. We need to examine the way in which certain teachings are presented, to demonstrate that we can be faithful to God without giving the impression that we are qualified to pass judgment on other people.

Not judging is a tricky thing to learn. The Lord Jesus never once asked for help with the task of judging others. We also believe we will all stand before him in judgment someday, and that those church teachings indicate in important ways what he expects of us. There is the tension.

The national synthesis highlights the goal of welcoming those who experience marginalization, and then observes that "Local communities report their experiences and hopes in this regard [becoming more welcoming], but also report the tension of not always knowing how to catechize and evangelize in a way that does not impede the welcome, and the desire to accompany with compassion the wounded in our Church and in wider society."

Here the drafters put their finger on another key tension that the synodal process must confront, one that is especially challenging for the U.S. church: Apologetics may be necessary in other regards, but it is a most unhelpful posture for the synodal process. You can't really listen to others if you think you have the answers already, and that the only challenge is forcing understanding.

The next sentence points to a source of unity in this process: "The local churches live this tension in the hope that synodal reflection on the level of the Universal Church will offer more guidance and direction so as to foster communion, strengthen participation, and effectively engage in the mission of the Church."

Apologetics may be necessary in other regards, but it is a most unhelpful posture for the synodal process. You can't really listen to others if you think you have the answers already.

That is to say, when doctrine is involved, the local church is not at liberty to change what it wants, but must consult with the universal church. The whole judges the part, and the church of Rome plays a unique role in that universal judgment. Almost all Catholics understand this.

Two other items pertaining to the synod process itself warrant attention, both of which are contained in the section "Ongoing Formation for Mission."

First, the "mission" as it was reported is not so much evangelization as improving the quality of parish life, mindful that the culture, actually the Catholic subculture, no longer carries the life of faith as it did with previous generations. The focus is more ad intra than ad extra. Scholars, especially those engaged in pastoral theology, need to flesh out these challenges in greater detail but also attend to what seems to me a key insight Pope Francis has made throughout his pontificate: We go to the marginalized to ameliorate their suffering but the effort will transform the church, will transform us, as well. Transformation is mentioned as one of the fruits of the synodal process, but it needs to be linked better with the ad extra call to evangelize, and to evangelize with our charity, proclaiming Christ's love in our deeds, using words when necessary.

N.B.: The section of "social mission" contains some additional insights here, but that subject warrants another column all its own.

Second, the synthesis quotes from the report of Region 5, the provinces of Louisville, Mobile, Alabama, and New Orleans, on the need for greater "formation for seminarians and those already ordained to better understand human and pastoral needs, cultural sensitivity and awareness, greater emphasis on social justice, sharing resources with the needy, balancing the adherence to the dogmatic teachings of the faith with care for the emotional needs of their parishioners, how to include the laity in decision-making and learning to speak the truth with empathy, creativity, and compassion." Here is a task bishops can start on tomorrow: better preparing the next generation of clergy who currently get their theology from internet sources rather than from Vatican II.

This national synthesis makes clear that synodality is not a silver bullet, but it is a different, and much needed, way of organizing and governing the church. As the Holy Father has said repeatedly, this is not parliamentarianism, it is about listening to the Holy Spirit spoken in the voice of the lived experience of the Christian faithful, and aligning that with the tradition of the church, the teachings of Sacred Scripture and the font of ecclesial life that is the Eucharist. This national synthesis report from the U.S. bishops' conference is a major step forward, and those who prepared it deserve all the praise in the world.