Pope Francis greets the crowd before celebrating Mass at the beach in Huanchaco, Peru, Jan. 20. (CNS/Paul Haring)

If a much-vaunted deal between the Vatican and China on naming bishops comes to be finalized this year, it will highlight the international assertiveness that has been a feature of Pope Francis' pontificate. Yet it will also be highly controversial, raising the issue of how far Rome truly grasps the contemporary dynamics of power and is to be trusted in handling them.

Over the five years since his March 2013 election, as the first pope of the global south, Francis has left the world in little doubt where his church stands on key contemporary issues. Much media coverage has focused on internal church divisions, with Catholic traditionalists resisting his pastoral reforms, but the Vatican's international presence has been growing steadily on his watch, in what some observers are now calling a new "diplomacy of mercy."

In his World Peace Day message at the start of 2018, the pope recalled one of his pontificate's great themes by urging compassion toward the more than 250 million migrants and refugees in the world. But his call for coordinated action and "responsible management of new and complex situations" appeared to shift the focus from purely moral advocacy to something more concrete. So did his recognition that the new century had brought "no real breakthrough" in tackling perennial conflicts that drove people from their homes.

Similar points were made when the pope visited Chile and Peru in mid-January, defending indigenous peoples against "powerful economic interests," and in late fall 2017 when he traveled to Myanmar and Bangladesh. In each case, while Francis won praise for championing human rights in principle, practical aspects of his stance were also questioned — such as his failure to defend Myanmar's persecuted Rohingya by name while in Myanmar.

Church's political clout

An agreement with communist-ruled China is expected to be similarly contested, with some welcoming it as a chance to restore unity to the Chinese church and others rejecting it as a betrayal of long-suffering Catholic communities.

Similar dilemmas were faced by Rome in communist-ruled Eastern Europe, when it was under constant pressure to grant local regimes the prestige and benefits of diplomatic ties in return for their promise to end persecution and normalize the church's status.

Questions of trust were never far below the surface. Did the Vatican really understand the communist mindset, and the strengths and weaknesses of communist rule? And while the Polish St. John Paul II unquestionably did, it's open to question whether this can be said of Francis.

However this is argued, Rome has some powerful assets to deploy in pursuit of its initiatives.

Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and Pope Francis smile during a 2016 meeting at José Martí International Airport in Havana. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The Holy See now has a permanent presence in some 40 international organizations, from the United Nations and its agencies to the Council of Europe, Arab League and Organization of American States, while Vatican Radio broadcasts in 47 languages —more than Voice of America or the BBC.

The pope himself has 40 million Twitter followers, and they're increasing by about 25 percent annually; Rome's Pontifical Gregorian University alone has students from at least 150 countries.

Meanwhile, the world's Catholic population has doubled in the last three decades to about 1.3 billion. By the end of 2015, there were 5,304 bishops, 415,656 priests and 670,320 women religious, as reported by the Vatican.

Even in countries with only small Catholic minorities, the church wields considerable clout. It remains one of the world's largest nongovernmental providers of education and health care. It's also one of the world's biggest aid donors, with Rome-based Caritas Internationalis coordinating Catholic organizations in some 200 countries.

As the nerve center of this highly organized network, the Vatican is also expanding its diplomatic presence. When Myanmar established relations last May, it was the 193rd country to do so, and the 111th to host a permanent Vatican nunciature.

Academics and journalists routinely ignore the Vatican's role, since it can't be quantified by political, economic or military criteria; it can't be measured according to the usual interplay of state interests. It is, after all, the world's smallest state, just 110 acres with an official population of 1,000.

Yet there's plenty of evidence to suggest its influence and outreach shouldn't be underestimated.

The 1929 Lateran Treaty, which settled the Vatican's modern status, followed six decades of marginalization since the loss of the Papal States in 1870 — an event that had ended a thousand years of temporal power on the Italian peninsula.

The popes had been way behind the curve in responding to contemporary world problems and had witnessed the dismantling of the church's power in Bismarck's Germany and France's anti-clerical Third Republic, followed by brutal assaults on its clergy and faithful in new revolutionary states like Spain and Russia.

Advertisement

But the Vatican's role was reasserted when it became part of the international system in the post-World War years. And by the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council, Rome was awash with agents and spies from governments eager to anticipate where the church would deploy its influence under Pope John XXIII's policy of aggiornamento, or opening up.

They were right to be interested.

Having become the first pope to leave Italy since 1809, Pope Paul VI went on to visit 20 countries, whereas his successor, John Paul II, visited 129 — some, such as the U.S., France and his native Poland, on multiple occasions.

Whatever critics might think of John Paul II's conservative stance on Catholic doctrine and church governance, his importance on the world stage could hardly be doubted.

The Polish pontiff was instrumental in the fall of dictatorships such as in the Philippines and Paraguay. He intervened in numerous disputes, opposing the doctrine of preemption in the post-9/11 "war on terror," and becoming a driving force in interfaith contacts, notably with Islam.

John Paul II's greatest political feat, helping bring down communist rule in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, is still widely ignored by those unwilling or unable to acknowledge the place of religion in world events.

But it was recognized as crucial by communist bosses themselves, including Poland's strongman, Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski, who, having deployed state power against the church, later conceded that the pope's spirited teachings had "reawakened hopes and expectations of change."

In 1997, the Soviet Union's last Communist Party ruler, Mikhail Gorbachev, praised John Paul II as "the world's most left-wing leader," citing his opposition to poverty and injustice and acknowledging that the end of communist rule would have been "impossible" without him.

Though every political challenge must be approached on its merits, the Polish pope's role in European communism's overthrow served as a template for peaceful church actions everywhere.

Precedents of John Paul II

John Paul II saw more clearly than his predecessors how spiritual loyalties could have political consequences. But he also concluded that violence was not the answer, since authoritarian and totalitarian regimes emerged stronger when challenged by force.

Using simple notions from Christian tradition, he reminded confused and demoralized people of truths and values they knew but had forgotten. What made them decisive was how they were spoken — not in the sedate settings of churches and convents, but in the full blare of city squares, industrial estates and suburban parks.

All of this was a striking turnaround from the humiliations of the 19th century, when Marx and Engels had denounced the papacy in their 1848 "Communist Manifesto" as one of the "powers of old Europe," and Pope Pius IX in his 1864 "Syllabus of Errors" had angrily refused to reconcile himself "with progress, liberalism and recent departures in civil society."

Whereas previous pontiffs, mesmerized by images of destruction from the French Revolution or the Paris Commune, had feared spontaneous social movements, John Paul II saw them as allies, a creative energy the church could harness for godly purposes.

The church had to find its own solution to problems communism had highlighted: labor-capital relations, work and property, exploitation and alienation. And it had to find positive, liberating impulses to set against the negative, captivating resentments communist rulers used as tools of power.

"Movements of solidarity," the phrase used in his 1981 encyclical, Laborem Exercens, could be friends, not foes, of Christianity — in achieving a moral victory over fear and hatred that ultimately became a political victory.

Pope Francis blesses a prisoner as he visits the Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility in Philadelphia in this Sept. 27, 2015, file photo. In Washington the pope visited the White House and made history as the first pope to address Congress; in New York he spoke at the U.N. and visited ground zero; in Philadelphia he led the World Meeting of Families. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The pope knew the power of words, symbols and images. In an era of economic globalization and mass communication, he sensed the power of governments was diminishing.

The fighters, tanks and missiles of the superpowers could destroy the world many times over. But without people to fly, drive and launch them, they were useless chunks of metal. It was with people and public opinion where the church's real power lay.

Recognition of that unprecedented outreach to world opinion, and readiness to mobilize it, was reflected in the political leaders who now made the Vatican a port of call.

Whereas no U.S. president had bothered to meet the pope for 40 years after President Woodrow Wilson's Rome visit in 1919, John Paul II had two meetings with Jimmy Carter in the space of half a year, followed by four with Ronald Reagan and four with Bill Clinton; President George W. Bush visited the Vatican five times.

A tradition of quiet diplomacy

When the Polish pope died in April 2005, his funeral was attended by 7,000 accredited journalists and at least 4 million people, the largest ever gathering of heads of state and government outside the United Nations. It was a sign of the importance attached to the Vatican by the world's decision makers and power brokers.

After the eight-year hiatus of Pope Benedict XVI, the Vatican's influence is now up and running again, as Francis speaks out against the death penalty, war, nuclear weapons, poverty, discrimination, corruption and organized crime. He demands firmer action, alongside the U.N., on behalf of the world's downtrodden and excluded.

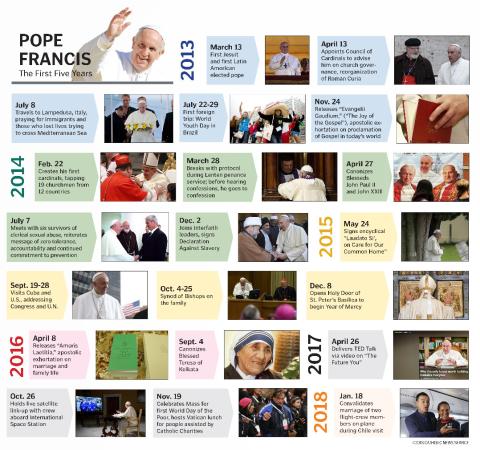

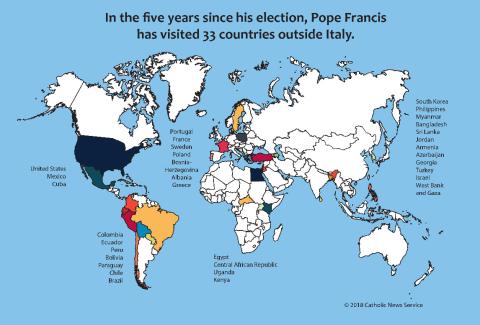

After expanding the global composition of the College of Cardinals, Francis has taken his message to 30 countries, including Israel and Palestine, Turkey, Cuba, Egypt and the Central African Republic; he has invitations to visit others, including South Sudan.

Meanwhile, Vatican diplomats have been heavily involved in peace negotiations in countries like Venezuela and Colombia and been vocal in international initiatives such as the U.N.'s 2018 Global Compact.

In Myanmar last November, Francis was aware he'd caused disappointment by not naming the hard-pressed Rohingya, telling journalists on his flight home "the door would have closed" if he'd done so. But his message had come across — and been heard clearly.

Though denied "the pleasure" of a public denunciation, he explained, he'd said "everything" in his meetings with government officials. And he'd instructed Myanmar's Catholic bishops to make their voices heard "for the dignity and rights of all, especially the poorest and most vulnerable."

When wounds are "both visible and invisible," a stern search for common ground sometimes helps more than headline-grabbing condemnations. That's an area in which the Vatican's traditions of diplomacy can still prove highly effective.

Will the same count with China?

Seasoned observers concur it's essential to differentiate clearly between local circumstances, all of which have to be studied painstakingly and understood intimately. In the world of complex church management, there can no "one size fits all" approach.

Some of Francis' outreach has already been bitterly opposed.

His February 2016 meeting in Cuba with Russia's Orthodox Patriarch Kirill provoked misgivings among Catholics in Ukraine and Eastern Europe, who feared it would give propaganda benefits to the Kremlin — a charge also levelled against the Vatican's Secretary of State, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, when he visited Moscow last August.

If the "diplomacy of mercy" is to work, it must go beyond worthy humanitarian aims and also be firmly grounded in reality.

For all the risks and dangers, however, Francis' peace-building efforts should be appreciated and followed carefully. They forcefully demonstrate how religion can still provide a foundation and orientation for effective, innovative action.

They also show how influential, self-confident church leaders can still play a role in promoting participation, citizenship, dialogue and reconciliation — and in opposing the "Herods of today," as Francis described them in his last Midnight Mass homily, leaders who merely seek to "impose their power and increase their wealth."

If China's regime sets out to exploit this, it can expect a payback in future.

[Jonathan Luxmoore covers church news from Oxford, England, and Warsaw, Poland. The God of the Gulag is his two-volume study of communist-era martyrs, published by Gracewing in 2016.]