On May 29, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York, a demonstrator who was arrested waits in the back of a bus during a protest against the death of George Floyd, a black man who was killed while being restrained by a Minneapolis police officer on Memorial Day that year. (AP/Frank Franklin II)

For many Americans, July Fourth is a day of celebration marked by fireworks, parades, barbecues, fairs, baseball games and various political ceremonies offered in remembrance of the country's declaration of sovereignty from British colonial rule. For the "founding fathers," the Declaration of Independence asserted particular freedoms for its citizens, specifically that "all men are created equal," and "are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights ... among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

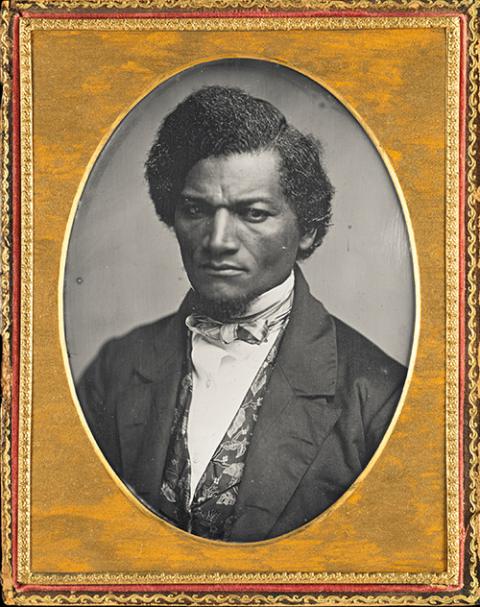

Despite this seemingly universal call to human dignity, for many Black and brown Americans July Fourth exists as a haunting and lingering reminder that such independence and freedom was never meant for them, a sentiment most poignantly expressed by the African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass in the summer of 1852:

A daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass, circa 1847-52 (Art Institute of Chicago)

This, for the purpose of this celebration, is the 4th of July. It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom. This, to you, is what the Passover was to the emancipated people of God. ...

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. ... The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. ... You may rejoice, I must mourn. ...

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

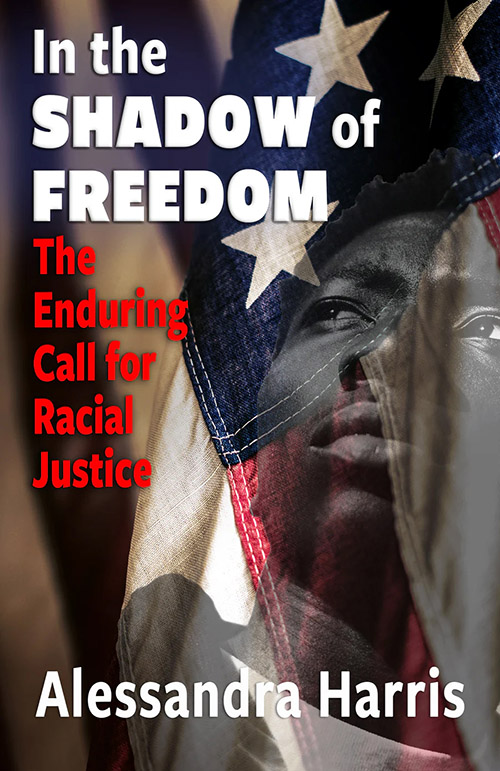

Black Catholic author Alessandra Harris revisits Douglass' famed speech in her new book, In the Shadow of Freedom: The Enduring Call for Racial Justice. She argues that in the 172 years since its deliverance, the four "peculiar institutions" that have marked the history of this country — chattel slavery (1619-1865), Jim Crow (1865-1965), northern ghettos (1915-1968) and hyperghettos and prisons (1968-present) — have now converged into the new peculiar institution of contemporary mass incarceration which includes militarized policing tactics, a multibillion-dollar prison industrial complex, extrajudicial police killings, racial profiling and post-incarceration social exclusion.

Harris writes that the U.S. alone incarcerates nearly 2 million people, the largest number of people in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the population in the history of the world.

Despite the fact that over the last 40 years the incarceration rates in the United States have increased by 500%, Harris asserts that too many in American society have become desensitized to this reality, coming to view grotesque racism and brutality as commonplace and even justifiable in extreme cases.

While she does acknowledge that the Black male incarceration rate declined substantially under President Barack Obama's tenure, America still spends more money on policing than nearly any country in the world — with Black men being disproportionately arrested, convicted and incarcerated.

A 2017 report on "Race and Wrongful Convictions," found that Black people were more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than their white counterparts.

Harris skillfully and convincingly argues that such realities cannot be viewed in isolation, and so offers a thorough treatment of each peculiar institution, beginning in the year 1441 when the European Christian slave trade began in Africa. The Catholic Church would be the first to legitimize the Portuguese's involvement in the trade with the 1452 and 1455 papal bulls Dum Diversas and Romanus Pontifex.

Over the next several hundred years, more than 12.5 million people would be captured and trafficked to the Americas with only 10.7 million surviving the Middle Passage. With the advent of chattel slavery came also the shift of the Black to that of a racialized subject, with both philosophical and theological justifications serving to reinforce ideologies of Blacks as subhuman.

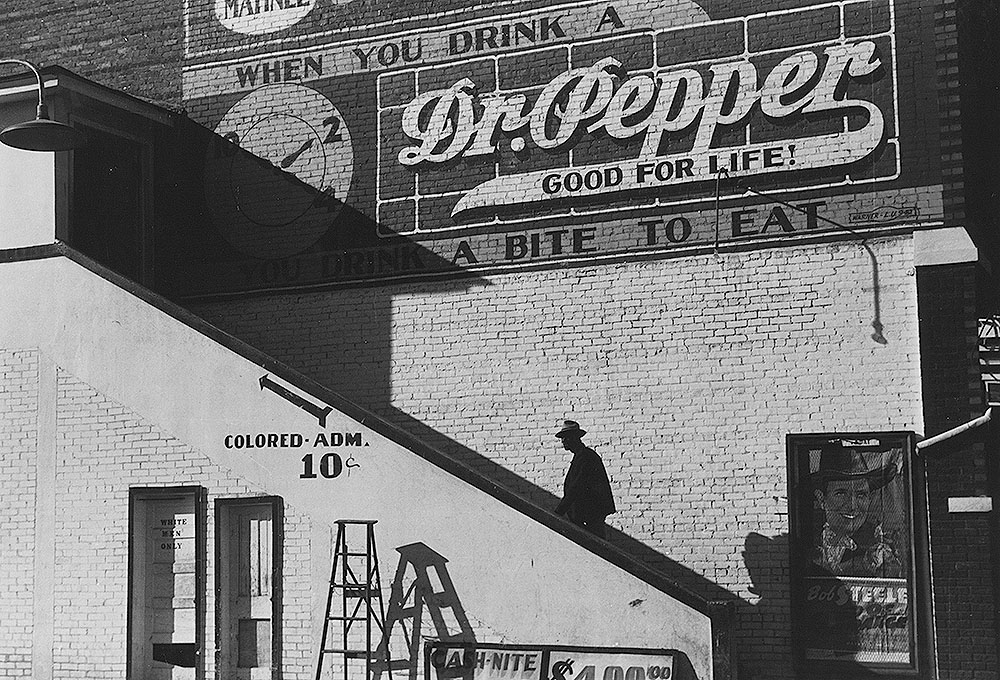

For Harris, the above would only shift into convict-leasing neoslavery after the Civil War, Jim Crow segregation that followed (and was reinforced by the terror of racial lynching), and now the death penalty, along with overpolicing and the disproportionate imprisonment of Black men.

A Black man enters a segregated movie theater in Belzoni, Mississippi, in 1939. (Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress)

Concerning what Harris calls America's new form of "Black lynching," statistics are offered from the Death Penalty Information Center, which estimates that 3% of executions that have occurred in the U.S. were botched (i.e., inmates catching fire during electrocutions, folks being strangled during hangings, or individuals receiving the wrong dose of lethal injections) between 1890 and 2010.

In fact, a 2017 report from the National Registry of Exonerations titled "Race and Wrongful Convictions in the United States," found that Black people were more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than their white counterparts, with those convicted being 50% more likely to be innocent than other racial groups. Furthermore, the Death Penalty Information Center has documented that since 1973, 189 people who were executed by capital punishment have been exonerated of all charges related to their conviction, 107 of those being Black men.

Regarding the disproportionate imprisonment of Black men, Harris points to the study "A Generational Shift: Race and the Declining Lifetime Risk of Imprisonment," which found that during the period known as the "prison boom" (1973-2009), " 'the number of individuals incarcerated in prisons increased by more than 700%,' Black men born during 1981 and 1984 being most impacted, with one in three incarcerated."

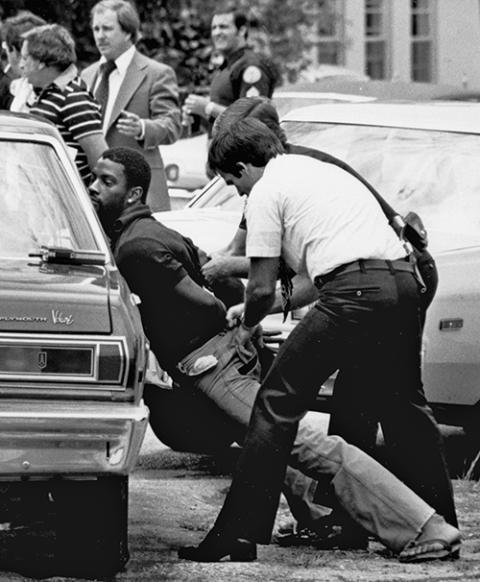

Police handcuff a suspect during a drug raid in Miami, May 18, 1979. (AP/Al Diaz, File)

The incarceration rates during the prison boom era were so pervasive that Black men were more likely to go to prison than obtain a college degree, marry or serve in the military.

At this same time, Harris argues that the infamous "War on Drugs" — disproportionately waged against the Black community, especially in inner cities and urban centers — was really a mechanism to reinstate a racial caste and control the Black population after the civil rights movement ended Jim Crow segregation. To support this claim, Harris juxtaposes the American government's current treatment of opioid addiction as a "crisis" (more than 600,000 people having died from an opioid overdose), as opposed to crack cocaine addiction in the '80s and '90s, which resulted in harsher sentencing mandates and convictions.

Moreover, the author examines how being born Black, concentrated poverty and gentrification, the traumas of domestic violence, abuse and untreated mental illnesses not only contribute to this ongoing cycle but also exacerbate and perpetuate it.

For instance, historic discrimination by the government that enforced segregation in housing and schools, alongside a lack of generational wealth, saw the development of underresourced schools in impoverished neighborhoods leading to what scholars have coined the "school-to-prison pipeline."

Between 1975 and 2018, many schools located in such regions (that also have a history of using disproportionate force on students) saw a dramatic increase in police and school resource officers, up from 1% to 58%.

Additionally, Harris found that early experiences of trauma, specifically sexual abuse or instances of mental illness among Black girls were a strong predictor of their entry into the juvenile justice system.

Advertisement

For Harris, it is no coincidence that during the same period of astronomical growth of prisons, the population of patients in psychiatric facilities shrank by 90%. A 2004 survey found that 38.1% of individuals incarcerated in a federal or state prison also identified as having a mental health disorder.

Such realities have spawned a moral crisis, and Harris urges those who identify as Christian or religious to not only understand and acknowledge this history, but root out white supremacy and anti-Blackness from their identity. Despite Christianity's universal call to love and dignify others, Harris asserts that American Christians harbor racist and intolerant positions at higher rates than nonbelievers.

The Catholic church is included in this indictment, having historically provided an initial blessing of the slave trade and being complicit in the owning, buying and selling of African slaves.

Thus, Harris concludes her study with what she calls a "Catholic Call for Justice" which she roots in Jesus' words in Matthew 25:37-40, arguing that for too long those who have claimed a moral and spiritual compass in America have failed to honor the dignity of the least of these. For Harris, a truly Christian approach to the dignity of others must be focused on both spiritual and economic/environmental justice.

Washington Auxiliary Bishop Roy Campbell and a woman religious walk with others toward the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington during an anti-racism protest June 8, 2020. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Luke's social Gospel — which outlines Jesus' ministry of salvation and liberation for those who suffer — and its continuation in the book of Acts supplement this reading, specifically that Jesus' primary mission was to "preach good news to the poor ... proclaim liberty to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to release the oppressed."

Practically speaking, this would look like civil engagement (i.e., voting, supporting social programs like SNAP, social security, health care, affordable housing, etc.); civil disobedience (i.e., protesting); and seeking reparation and restorative, rather than retributive, justice.

This book comes as a welcome companion text to works such as The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander, Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and Illusion of Safety and Freedom by Vincent Schiraldi and Until We Reckon: Violence, Mass Incarceration, and a Road to Repair by Danielle Sered — as well as Benedictine Fr. Cyprian Davis' The History of Black Catholics in the United States, Fr. Bryan Massingale's Racial Justice and the Catholic Church and the Rev. James Cone's The Cross and the Lynching Tree.

Harris' effortless weaving of political science and law into the disciplines of Black studies, African American and Black religious history, theology and ethics is impressive, doing so in a way that is highly accessible to those outside of formal academia.

I echo Harris' challenge to her readership that a truly Catholic vision of abundant life in Christ looks like the church inviting those on the margins out of the shadows and into the light of freedom and flourishing.

Then, and only then, will the message of the Gospel be good news.